It's hard to imagine just how radical he and his cohorts were back then, almost 200 years ago, how far off the path they walked, listening, as he would have said, to "a different drummer." New Englanders weren't the only white men and women in the world to oppose slavery, but abolition, almost anywhere in America, was a fringe notion when Emerson and Thoreau and the New England transcendentalists preached it.

It's hard to imagine why today, but that abolition was so very radical is no less a fact. If you opposed the institution of slavery, that "peculiar institution," as people called it, you were suspect in most circles.

My family's history in North America begins after the Civil War for the most part. What's more, clannish Dutch immigrants determined long before they left the Netherlands that they would live north of Mason-Dixen. The long history of Dutch slave trade notwithstanding, the orthodox Protestants I come from stayed away from slavery.

All of which makes understanding how very radical the cause of abolition was even more difficult. Try to imagine a world in which city ordinances forbade more than five slaves from talking to one another on the street, where black people who didn't step off the sidewalk for whites would find themselves in the city jail, where slaves were, by law, commanded to leave town one year after being freed.

That white men and women like me live downriver from all of that is difficult to remember and a powerful advantage most of us don't consider. Even after the Civil War, most whites, North and South, didn't believe black people were fully and truly human. There's good evidence to show that Abraham Kuyper didn't. A century after John Brown's mad attack at Harper's Ferry, my pious Dutch Reformed grandpa didn't. More than a century after Appomattox, I'm not altogether sure my father did.

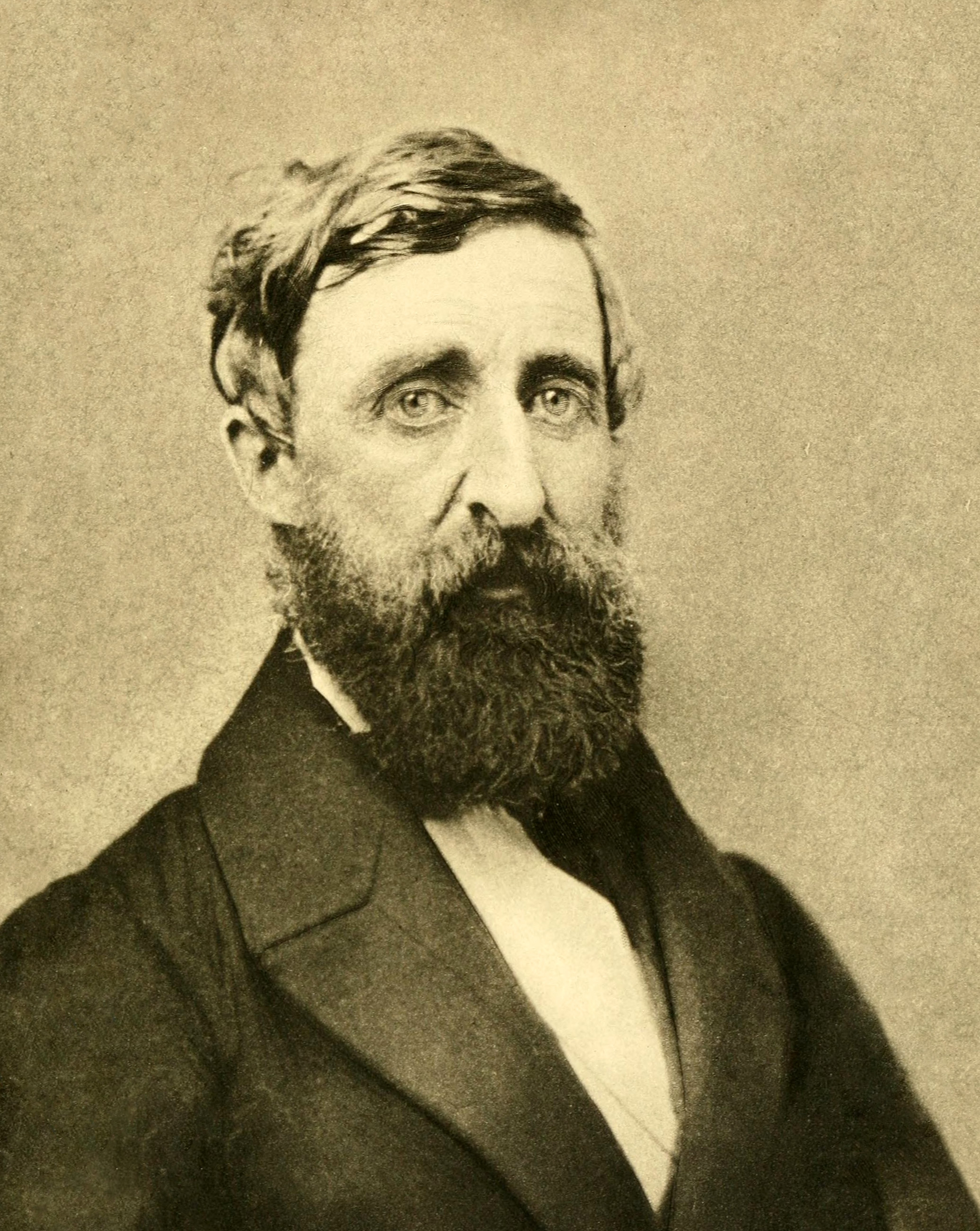

I'm not even sure about Henry David Thoreau. Just because you were an abolitionist didn't mean you believed in racial equality. More whites believed that slaves should be freed than believed they should be able to vote.

But Thoreau himself "conducted" on the Underground Railroad, helped freed slaves, and was one of very few who defended John Brown after the raid that failed so miserably: "There are absolute moments in life," he once wrote, "when absolute action must be taken against absolute evil."

It's Thoreau's birthday today. When I look outside the basement window at the gathering dawn what I think about is Thoreau's deep love for that world, the world of nature, which he watched religiously through the two years he spent at Walden Pond.

But Thoreau was also an abolitionist, a radical. He believed no man or woman should own another, regardless of color, a belief that required a hundred years and more for some of his countrymen to share.

Anyway, it's his birthday today, and, for me at least, that's cause to celebrate.

What's more, after last week's toll of racial horrors, for so many reasons it's also a morning to give thanks.

1 comment:

The long history of Dutch slave trade notwithstanding

It is widely believed that slave trading stopped world wide on Jewish holidays. The debtor being the slave of the creditor, I have accepted lately that the slavery remains constant, but it's forms change. The self-rightous posing and condensension of the abolitionist comes down to a lot of hot air.

I believe that Uncle Tom's cabin was written by a women who never visited the South. The battle hym of the Republic remains a sort of Unitarian (Transcedentalist) delusion.

As far as Dutch influence goes "there is an anvil on which many hammers have been destroyed."

The History of Jewish Influence

Dr. Andrew Joyce - The History of Jewish Influence

18

Jun 02, 2016

thanks,

Jerry

Post a Comment