Morning Thanks

Garrison Keillor once said we'd all be better off if we all started the day by giving thanks for just one thing. I'll try.

Monday, September 25, 2017

Desert Sojourn

Vacation? Well, hardly. But I'll be gone for the next week or so, bound for the Great Southwest. If you visit here regularly, you won't find anything new for a while, but I'll be back in a week or so.

Sunday, September 24, 2017

Sunday Morning Meds--Wounds and faith

“He heals the

brokenhearted and binds up their wounds.” Psalm 147:3

A few

years ago already, our newspaper cunningly stopped doing obituaries for free;

today you pay. Those notices still spread over two whole pages; because even

though no one has ever escaped it, death is still news.

And yet,

if you spend any time in an old folks’ home, you realize how many old folks leave

this world almost seamlessly. Some deaths, however, are never to be forgotten.

Years

ago, a high school senior fell to a mysterious killer that slowly took her life

away, while all around her—even in her hospital room—hundreds of prayers arose

daily. A teacher at the Christian high school she attended told me that year

was the worst he’d ever spent in a classroom because the kids—unaccustomed to

death and given to fervent emotions—simply couldn’t study, their good friend in

deadly anguish for so very long. She was dying, and no one—not even God

almighty—seemed able to lift a finger.

It took

months, but a death that once seemed beyond belief came on inexorably. Months

after she first felt some ordinary flu symptoms, she fell to a mystery—mercifully,

I suppose. Try to imagine the minds, hearts, and souls of her parents, the

endless, heartfelt prayers of hundreds of high school friends.

One of

the most difficult lessons is that there are times when God doesn’t seem to

answer prayers, no matter how arduously we beg. Sometimes we just don’t get

what we want, even when what all we want is precious life.

It’s been

years now, but her parents carry wounds whose flow of grief has never been

fully stanched. Their daughter’s death stands

in their souls like a black obelisk of cut glass, and it will be that way until

the day each of them are gone.

Long ago,

life in that high school returned to normal. Talking about what happened so

many years ago would be as ho-hum today as a power point on the Peloponnesian

wars. A few staff remember, but most who

were there are gone. Someplace in a hallway her picture may be hanging, but none

of the students who daily open lockers nearby have any idea of who she is or

was.

Even

though we know mysterious killers stalk the countryside, believers like me live

in the assurance that assertions like verse three— “he heals the

brokenhearted”—aren’t just cheerleading. Faith somehow consents to the

illogical assertion that somehow, He will be there, even though it seems he’s out

of the building, that, as promised, he will heal, he will bind up our wounds. Faith

sinks its teeth into that promise and just tries to hold on.

Friday, September 22, 2017

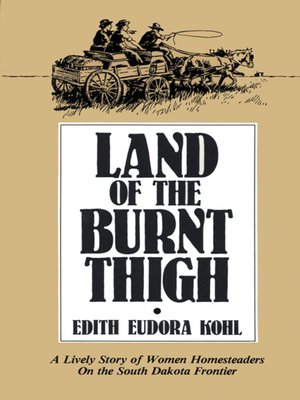

Book Review--Land of the Burnt Thigh

The incredible speed of the transformation of the untouched plains; the invasion of the settlers in droves, lighting on the prairies like grasshoppers; the appearance, morning after morning, of new shacks, as though they had sprung up overnight; the sound of hammers echoing through the clear, light air; plows at last tearing at the unbroken ground—the wonder of it leaves me staggered now, but then I was caught up in the breathless rush, the mad activity to get things done.A South Dakota rancher from west river told me I really should read The Land of the Burnt Thigh, a kind of homesteading memoir by Edith Eudora Kohl, and I'm glad she did. By definition, I suppose, the book is a novel, because Kohl uses her own life in the telling, and her sister's; but she compliments their story with the lives of other women homesteaders she knew in a telling that documents how really tough it was for men and women, white men and women, to put down roots on land that had really never been broken.

That it had never been broken doesn't mean, of course, that it was uninhabited. There were people throughout that endless grassland, people who hadn't determined the land beneath their feet was theirs to "break," to "conquer." "The buffalo and the Indian had each had his day on this land," Ms. Kohl says, "and each had gone without leaving a trace." The blindness in what she sees is almost as breathtaking as the land she describes so richly. But there's no lament here, no memory, and nothing but awe in the face of human possibilities.

It was untouched. And as far as the eye could see, it stretched, golden under the rays of the setting sun. Whether the magnitude of the task ahead frightened or exhilarated them, the landseekers were all a little awed at that moment. Even I, seeing the endless sweep of that sea of golden grass, forgot for the moment the dry crackling sound of it under wheel and foot, and the awful monotony of its endlessness which could be so nerve-racking.Ms. Kohl writes very well. It's hard not to get swept away in the rhapsody she creates. If the story is closely biographical, it's clear that Ms. Kohl and her sister, adventurers from out east, never intended to stay in South Dakota. Once they arrived and found the tar-paper shack some crook told them was a house, they could think of nothing but leaving, maybe even the next day.

But they fell in love with the openness, the freedom, the opportunity, the creativity required simply to live and even to flourish. Last year at this time, I spent two weeks at the National Homestead Monument, just outside of Beatrice, Nebraska, a place that tells the epic story of ordinary people making a life out of a land that wasn't and still isn't all that hospitable. The poverty was immense, the heat unbearable, the cold deathly, the winds constant. That story Edith Eudora Kohl tells and tells movingly.

But what she doesn't see, what her racism blinds her to, is the displacement of a people and a culture who thrived on the plains, "a people who had gone without leaving a trace," she says, eyes shut tight. I really like the book, but anyone who's read Black Elk Speaks can't help but be shocked at what Ms. Kohl doesn't see.

Mark Charles is a Navajo activist, writer, and speaker, who says unequivocally that one of the reasons for the divides which exist and even threaten this country and its people is the fact that we have no collective story. We tell and believe different histories. Until we can create a story together, we'll not live in the same world.

Edith Eudora Kohl's The Land of the Burnt Thigh is a lovely book. It really is. I enjoyed reading it. It documents the hard road white people took to make a Great Plains home for themselves. I'm glad that west river rancher told me it was a book I had to read. She was absolutely right.

But The Land of the Burnt Thigh is also an embarrassment. It documents the racism of white man's blindness. In so many ways, it's a memoir that has so much teach.

Thursday, September 21, 2017

Small Wonders--Maria Pearson

This story begins during the summer of 1971, on Highway 34, southwest Iowa, with a digger, some lumbering monster doing dirt work, widening the highway maybe—I don’t know. It starts with some huge machine with healthy jaws opening the earth and eating it, a monster which had to stop munching when the ancient graves of 28 people got in the way.

That night, one of the men, a district engineer with the Iowa Highway Commission, a man named John Pearson, came home to Maria, his wife, with the news.

I don’t know how Mr. and Mrs. Pearson started talking, but let’s pretend Maria asked him a standard, spousal question: “Well, dear, now tell me, how was your day?”

Okay, that’s unlikely, given what we know of Maria. Most who knew her would steadfastly declare Maria was no June Cleaver, a fact which husband John must have known only too well because the story says he preceded his news of the day with a stern warning: “Sweetheart,” he said, “you’re not going to like this.”

And he was right on the money with that one. She didn’t.

Because she didn’t, her world—and his and ours—changed at that very moment.

John Pearson told Maria that when his road crew turned up the graves of 28 people that day, 26 were set for reburial at an previously appointed place just up the road. Two of them, however, were not--a mother and child, whose remains were sent to the office of the State Archaeologist in Iowa City.

Because they were Indians.

As was Maria Pearson, born and reared on the Yankton Reservation, where as a member of the Turtle Clan, she was named Running Moccasins, and where her grandmother made sure her granddaughter learned everything she should know about her Native people and their ways.

What the Pearsons had for supper isn’t written up anywhere, but John wasn’t wrong—his wife was hot. The two of them barely finished drying the dishes before Maria left for Des Moines, where she stormed the office of then Governor Robert Ray—and then Iowa City, where she ambushed Marshall McKusick, the State Archaeologist.

She wasn’t demanding special treatment, only equal treatment. What she told them both is that she expected the remains of that Native mother and child to be buried just like the others, not stored in some museum or lab like a dead bull snake. She got so mad she sat—that’s right—she sat on the governor’s office desk, even though she’d never been there before. She could barely contain her righteous indignation.

And that was only the beginning. Maria Pearson spent the rest of her born days making sure honor was granted where it was due, creating the nation’s first legislation to protect Native American graves and provide for repatriation of remains. Those state laws led to what some call “the most significant legislation pertaining to Native American cultural identity since the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924.”

Wasn’t easy either. Mary Pearson took on politicians, museum officials, and the scientific community, to create the landmark Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act of 1990, which protected the rights of Native Americans “to certain human remains, funerary objects, sacred objects, and objects of cultural patrimony with which they are affiliated.”

At the core of the arguments was Maria Pearson’s Native religion, a religion that holds that the past and present are one and that a person’s spirit abides with their remains. When those remains are disturbed, their spirits grow unsettled and unhappy. Standing Bear’s argument for taking his band of Poncas back, once again, on the long walk from Oklahoma was that he had promised his son he would be buried with his ancestors overlooking the Niobrara.

Maria Pearson, through all those years of activism, liked to tell people she heard her grandmother’s voice in the leaves of a cottonwood gently shaking in prairie winds. And what her grandma told her in the voice of those trees—make no mistake about it because Mary Pearson didn’t—was that her granddaughter named Running Moccasins should always and stand up for her people.

When, that first day in the governor’s office, he asked her what it was she wanted, she told him. "You can give me back my people's bones,” she said, “and stop digging them up."

Twice, Maria Pearson was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize for her work in preserving once abundant communities all around us.

“You’re not going to like this,” her husband said. He was right.

Wednesday, September 20, 2017

Morning Thanks--a growing lawn once more

The old one started good, cut cleanly, purred like pet. When I bought it, years ago, it was the bottom of the line at the Coop, but the Coop doesn't sell junk. It was doing well, but it was tiny, and once we moved, we had a huge lawn.

At the old place I had a rider too, especially for the leaves that swamped the place every October, knee-high if I didn't pick them up three or four times a fall. That rider was model A, an ancient Toro I bought, used, twenty years before, when I had to find some way dang way to deal with those massive lindens and their frying pan leaves. I sold that old buggy before we left.

The old walk-behind is gone too. It was just too small. The new one is huge, a Timemaster no less. We planted a goodly chunk of our acre with native wild flowers, and, first year, cut it just as often as the lawn, so the new lawn mower had to take a big bite. I figured, retired, I needed the exercise. It's not a rider.

Wasn't cheap, but it starts quick, cuts cleanly, purrs like a pet, and takes out a swath of lawn a yard across. Okay, that's stretching it.

Last year I used that tank of a mower all the time. Enjoyed it too. Told myself for once I'd made a good decision. This year I stopped mowing the prairie, let all those wildflowers grow. Otherwise, nothing's changed except the weather, which didn't seem anywhere near a drought; but for some reason the grass never grew a whole lot, didn't brown either just took the summer off.

So that tank mower spent most the summer in the garage, which is fine. It's not a Lamborghini or some big, bad Harley. I'm not dying to get it out on the road.

But there's just enough cool and just enough rain these September days to make all that emerald around the house shine again, almost like spring. With the big spindly sunflowers and the blossoming asters, a few flashy greenhouse annuals, and those clattering aspens, there's green out back and all around, summer's last show. It's time to get out the big mower.

Retirement is real joy in just little things. I've always enjoyed cutting lawn, but never got up smiling, knowing that new Toro would start on the very first pull. Today, I won't change the world, I'll only mow the lawn. And that's just fine with me.

This morning, I'm thankful for a September lawn that's lush and green and the opportunity to take the time to love it.

Tuesday, September 19, 2017

Morning Thanks--the clean-up crew

I'm about to say something that should make generations of students, my students, irate. It's a confession, and confession is good for the soul, or so I've been told. Trust me, it's not easy admitting this. I'm five years on the other side of a classroom career, far enough away to believe I'm free to say what I need to, although I may have to lawyer-up.

I taught English for forty years and read thousands and thousands of student essays, even enjoyed it. Not everyone can do that and not everyone can say that, but I can. I'm not lying.

But I am sidestepping. I promised a soul-scorching confession, and now I'm just dancing. (Deep breath). Okay, here goes. I'm a ridiculously bad proofreader. Proofreading is a job I can't do, a skill I don't have, an art I can't practice. I know people who are good. I know people who are terrific. I'm not.

I've graded countless papers, marked them up in war paint, dressed them up--and down, cajoled, upbraided, stroked, sweet-talked, massaged, sent kids to their doom and brought them close to classroom glory, tens of thousands of 'em; and for all that time, red pen in hand, I was a outright fraud.

I've officially given up on a novel I've had around for years, finally determined that at 70 years old I'll never see it in print if I don't publish it myself. I'm too old to get some whipper-snapping agent to take me on. It's not like I've got a dozen novels in me anymore--I don't.

Besides, publishing is a whole new world these days. Everybody's self-publishing--well, just about everybody. If you're a celebrity, publishers will beat your door down for whatever ink you can muster. But if you're a schmo, good luck. Still, a couple hundred publishers will be glad to take your money.

That means I've got to do the hard work--proofreading--and I can't. An old friend of mine says that in order to proof well you got to go through the manuscript backwards. Sure. I can't.

That doesn't mean I don't try. I read a sentence, any sentence, and tell myself I can do better; so I delete half of what's there or add a dependent clause or two. I combine sentences, check the thesaurus, manipulate character, throw a little more salt into plot. In other words, I read twenty pages and what's behind me is a bloody battlefield that's got to be proofed again because I can't change things wholesale and expect spotlessness. I've got to do it again--fourth time, fifth time.

And when I do, I slip right back into editing, changing sentences, cutting out the fat, making things better. I can't help it.

Really good proofreading creates sinless copy. Really good editing makes it saintly. But saints can't be sinners. Dumb thing's got to be clean. I'm a decent editor, but a hopeless proofreader.

So I enlist my wife, who's much better.

Anyway, here's hoping. Today, I'll type in her final corrections. That's it. No more. Just what she marked.

Fat chance.

When finally this novel comes out, I'll have nightmares starring old friends who will shake their heads and whisper to each other that Schaap is losing it. I can see it already.

This morning, this woebegone writer is thankful there are those who have, throughout my life, accomplished a job at which I am worthless. Proofreaders are good men and women adept at cleaning up after those of us who can't. They're the saints, my wife among 'em.

Monday, September 18, 2017

Morning Thanks--Monarchs among the asters

I won't try to be something I'm not. The fact is, I didn't "walk beans" often in my life, but I did do enough acres to know farming wasn't for me. My father-in-law was very specific when it came to identifying the enemy, and one of the villains was milkweed because, he said, that stuff has a lateral root--you chop it off here and it just comes up again over there, a beast of the bean field. Then he'd give me my machete, and we'd start walking.

Lo and behold, that very hated milkweed is fundamental foodstuff to monarchs. Dad didn't know that, and neither did I. Keep milkweed out of the soybeans and you make it tough for monarchs to find apartments when they need to because that pernicious milkweed is the only domicile they'll take. Monarch caterpillars are insanely picky eaters.

So I was thrilled, really, when the little acre behind our house birthed a half colony of milkweed this year. Last year maybe three plants came up--that's it. This year there must be a dozen.

Now you don't have to be a horticulturist to see that these monarchs, yesterday, were nowhere near the milkweed. They were thrilled by an aster bush.

No matter. I was happy enough to see them, and in volume. Once in a great while, a few individualist monarchs flitted through the backyard, but yesterday, for reasons all their own, six or eight chose to dine at once on the asters, playing peek-a-boo with me and the camera.

Nah, that's not true. They were busy and pretty much oblivious to me.

The sun was behind the clouds, or else these pics would be stunning. But the monarchs were anyway, and I felt grateful to host 'em. Monarchs in their unabashed beauty are ridiculously fragile for royalty. If they were really kings, there'd be no war.

Monarchs among the Asters sounds like a novel by F. Scott Fitzgerald.

It's about time for them to pack up for Mexico. Yesterday, that end-of-summer cool rode in the air like a blessing. Here and there, whole cornfields are already gone for silage, and where the beans aren't yellowed, they're clearly on their way. Another growing season is behind us, sadly enough, which may have made this whole drama even more comely. Soon enough they'll be gone, the monarchs and the asters.

So, gather ye rosebuds while ye can, as the poet saith.

The asters aren't bad either, but this morning I'm thankful the fanciest nomads on the plains, royalty to be sure, just happened to stop by.

Sunday, September 17, 2017

Sunday Morning Meds--Frauds and grace

“The LORD builds up

Jerusalem;

he gathers the exiles of Israel.” Psalm 147:2

At least

Arthur Dimmesdale wasn’t married. At

least there wasn’t a a wife and kids around to suffer the dismal fallout of

their husband and father’s tryst with Hester Prynne. At least Dimmesdale was a bachelor when he

dirtied the sheets.

Not so

the latest evangelical pastor to bite the dust—he had a wife and

children, not to mention a church of some 15,000 souls in the heart of the suburbs. Not only that, but the whole sordid truth

came gurgling forth, like hot tar, right before a national election in which,

as his congregation would have it, the forces of evil were so obviously pitted

against the forces of God—or their side.

And now there’s a fox in the hen house, or, to put it more boldly, a real

rooster. So much for family values.

The whole

truth wasn’t as ordered as the army of the faithful assumed it was. The general

got himself tripped on his own lance, so to speak, and he’s limping today, groveling as

well he should. After all, it’s one thing for him to have done what he did,

quite another for him to have acted for so long as if he were blameless.

Dante

relegated hypocrites to the lowest circles of hell because he thought of fraud,

a peculiarly human sin, especially displeasing to God. Sexual vices are only sins

of the flesh, not the spirit; you can do much worse than love someone when you

should not. But when humans deliberately mislead people who are in their trust, especially when it's done with false piety, Dante considered that kind of hypocrisy particularly evil

and put its practitioners way down there on circle eight of the Inferno, with Cain and Judas, where

the heat is really bad.

The

fallen pastor wrote out a confession of his sin, and when that confession was

read to his congregation, many of the parishioners explained quickly that they

were ready to forgive. Wonderful. We no longer live in Puritan New England. The question is, will they perhaps rethink some of the ardor of

their political judgments? Will be they at least a bit less quick to judge

others?

Probably

not. What characterizes contemporary

American evangelicalism these days is its forever carping tone, its commitment to drawing

lines in the sand. Changing that is not easy, even when their preacher

confesses to the sin they most despise.

The glory

of this verse of Psalm 147, the truth of the scripture itself, is that God will

gather his own as he sees fit. He will use his own interpretation of his

revelation, not ours. He won’t really care who we vote for or whether folks are

murderers or sleaze-balls, gangsters or self-righteous snobs. He’ll reach

down into the lowest circles of our conceptions of hell and pull out overheated

hypocrites. He’ll offer grace hither and yon, broadcast his love throughout the

cosmos. Count on this: He’s much bigger than we are.

The

shocking truth of the scripture is that, even if God almighty creates our

theological coloring books, he never stays within the lines himself. And that’s good news. Not only does God have

a place in his grace for those who the preacher and his people despise, he’s even

got room for the preacher.

He’s

always bigger, always greater than we are, always cleaning up after us, always

gathering the sheep who wander, as all of us do.

"He

gathers the exiles of Israel." That’s us, and that’s the gospel truth.

Friday, September 15, 2017

Small Wonder(s)--Tales of the soddie

The word is that we're sort of unique in Iowa, the only corner where people cut sod to create their first dwellings. What passed for housing for quite some time after Euro-Americans moved in were lean-tos and sod houses, domiciles whose thick walls created a level of insulation against ridiculous seasonal extremes that Siouxland dwellings haven't experienced since, I'm sure.

But soddies were nobody's dream homes. Why not? The neighbors, for one, creatures God meant to be outside the walls of human habitation, not in. The fact it, lean-to families never knew what kind of critter might emerge from the dirt ceiling and make himself at home, here and there a gopher or ground squirrel maybe, all manner of vermin, even an occasional garter snake. Creepy things, not house guests.

And rain. Anything significant and mud floors were the pits, literally. Sod houses were dark and wet and clammy and impossible to clean. When it didn't rain, the dust could stifle you. It's a marvel those immigrant Dutch women didn't suffer more breakdowns, living in dirt the way they did. If I'd look out my back window over a couple miles of rich prairie, it would likely take some work to see the neighbors, not because of distance, but because those lean-tos and sod houses blended in so well. The prairie school of Frank Lloyd Wright?--who cares. Sod houses were from the earth, in the earth, and of the earth.

I've never done a search, but I don't believe I've ever heard a prairie hymn brimming with nostalgia for good old days in a soddie. I don't know that I've ever seen a sod house in a movie or a TV show. They were meant to function, to make do. They were dirt-filled starter houses any family could build. But I don't think anyone ever liked them.

Minnesota's Laura Ingalls Wilder museum will send you on a road trip to see a hole in the ground on the bank of creek, the place where little Miss Laura lived before there was a little house on the prairie. That show ran for years and never put her in sod. Yucch.

Sod houses were how you got by until you got wood. They were what people lived in when they tried their best to put down roots in a land only the Yanktons had ever lived in with any joy. They had to be built, but didn't have to be loved. No one's first real home was ever so joyfully left behind.

No matter. There are a thousand good reasons to remember the place sod houses hold down in the epic drama of the Great Plains, even if there aren't a thousand stories people love to tell.

But here's one. It was time for huis bezoek, an old Dutch Calvinist ritual for which there is no English translation. The preacher was coming to visit, along with an elder, to speak and pray and to determine thereby, formally and formidably, evidence of righteousness.

There simply weren't chairs enough in the sod house that day, so Pa hauled in a couple of pumpkins. That late afternoon, for huis bezoek, Dominie Vander Snipe and his sidekick elder sat on pumpkins and quizzed the family on the Heidelburger.

It pains me to say it, but you have to be really old to like that story. Today, it won't be worth mentioning. Today, I'll be stationed right at the sod house at Sioux Center's Heritage Village when 900 school kids come through, look around, amazed, in the darkness, and, if they dare, touch the walls. It's a good job--trust me. I've done it before. Those kids can't believe people actually lived in such places.

But they did, and today it's my job to let all those kids know where they come from. Ought to be fun.

Thursday, September 14, 2017

September mists*

A fine mist seemed to flow, hither and yon, across the land west of town. You'd drive in an out in a minute, really, but when the sun came up--there were some clouds out east--that fine mist made the world something special, running like water through low spots. For the life of me I couldn't figure out why it would be in just beyond some hilltops and not beyond others.

It'll take a better photographer than I am to get that stuff into the camera. The camera itself doesn't know quite what to do with it. A ton of exposures simply weren't there, as if that electrical brain inside went nuts trying to determine what the idiot snapping the shutter wanted to get.

Ran into some pretty nasty looking spiders who create these elaborate webs in the grass. Just amazing. With just a bit of dew, those intricate webs hang like ropes. Those spiders are unbelievable weavers.

It was good to get back out again, and the morning was beautiful, even if I didn't get it all through the lens and into the files. Siouxland is yellowing deeply, the soybeans ripening, and the corn starting to get to that place where the crackling makes it noisy, even in a breeze. June's astounding emerald is almost overwhelming, but right now the variegated sloping hills west toward the river are a quilt of many colors. And that's good too.

_____________________________

How chunks of Siouxland looked on September 26, 2009.

Wednesday, September 13, 2017

Life among the white Protestants

Last week, Jennifer Rubin, a conservative Washington Post columnist but a confirmed "no-Trumper," used the findings of the Public Religion Research Institute to explain what some of us--me included--might well call Trump's super glue, whatever it is that bonds him and his loyalists. "I could stand in the middle of 5th Avenue and shoot somebody and I wouldn't lose voters," he said right here at Dordt College. Amid falsehoods all around (Obama's wire-taps, size of inauguration crowds, three million illegal New Hampshires, etc., etc., etc.), that line was honest-to-goodness truth.

White Christians, once the dominant religious group in the U.S., now account for fewer than half of all adults living in the country. Today, fewer than half of all states are majority white Christian. As recently as 2007, 39 states had majority white Christian populations. …Those are depressing stats for someone like me, white and Protestant. That me and my ilk are a rapidly becoming a minority is not news; discovering that the feeling isn't some personalized species of religious paranoia, however, makes me even more weary.

Today, only 43% of Americans identify as white and Christian, and only 30% as white and Protestant. In 1976, roughly eight in ten (81%) Americans identified as white and identified with a Christian denomination, and a majority (55%) were white Protestants.

When I was a child, no institution was more formidable than the church. What it held--the keys to identifying sin and redemption--was vastly more important than politics. That it had so much authority wasn't necessarily a blessing. After all, a lot of horror and injustice was created by an institution with that much unchecked power. Regardless, that era is long gone--and with the church's power itself. My people and my institutions seem running out of steam.

I've always assumed Sioux County religious folk vote for King and voted for Trump for a few reasons: 1) they want an end to abortion--that's a religious reason; 2) they are Republican--that's a political and familial reason. But could there be a third? 3) they are losing power to outsiders--and is that a racial reason?

The new findings of the Public Religion Research Institute suggest, Rubin says, that the fawning adulation of President Trump (and Representative Steve King) by white Protestants may well be rooted just as deeply in race as it is in religion.

No religious group is more closely tied to the Republican Party than white evangelical Protestants. Nearly half (49%) of white evangelical Protestants identify as Republican, about one-third (31%) are independent, and just 14% are Democratic. Mormons also lean heavily Republican, with more than four in ten (44%) identifying with the GOP, compared to 12% who are Democrats. White mainline Protestants (34% Republican, 26% Democrat) and white Catholics (34% Republican, 26% Democrat) also lean more toward the Republican Party.Every other year, Sioux County gives Rep. Steve King ("calves like cantaloupes") another term. When people talk about statesmen in the House of Representatives, don't look for his name in the among 'em--except here. His positions on immigration place him well to the right of mean, even though here, a robust economy would fall flat on its face without a labor force heavily populated with immigrants.

I've always assumed Sioux County religious folk vote for King and voted for Trump for a few reasons: 1) they want an end to abortion--that's a religious reason; 2) they are Republican--that's a political and familial reason. But could there be a third? 3) they are losing power to outsiders--and is that a racial reason?

The new findings of the Public Religion Research Institute suggest, Rubin says, that the fawning adulation of President Trump (and Representative Steve King) by white Protestants may well be rooted just as deeply in race as it is in religion.

White working-class voters who say they often feel like a stranger in their own land and who believe the U.S. needs protecting against foreign influence were 3.5 times more likely to favor Trump than those who did not share these concerns.As white Protestants watch their power diminish all around, even in Wal-Mart, is it a stretch to believe their voting patterns, here and elsewhere, have racial roots too?

White working-class voters who favored deporting immigrants living in the country illegally were 3.3 times more likely to express a preference for Trump than those who did not.

Tuesday, September 12, 2017

Privy Blessings

I was only there for two summers. I'm sure there were young guys like me who worked there longer, so it's entirely possible I can't claim a place in the Guinness Book of Records. But given the number of pit toilets I cleaned in a my lifetime, I deserve a title. Whatever the number, let it be known henceforth that I scrubbed far, far more than my share because a couple of dozen of privies remained in faithful service at Terry Andrea State Park, where I worked for a couple of summers a thousand years ago.

And those privies had to be cleaned. Daily. Twice even, if park visitors swarmed to the beach. That meant everything too--what was left on the floor and didn't make the target? You bet. When it comes to privies, I'm a vet.

People who spend years spreading thick frosting on cinnamon rolls get so tired of it that all that frosting eventually give them the creeps, I'm told. Hard as that it to believe, it may be true. Ain't no frosting on privies, but, trust me, when it comes to pits, familiarity breeds contempt.

But there's more. I have a special distaste for the ones that need to be cleaned. Like yesterday, at Spirit Mound State Park, where whoever had the job was clearly absent without leave. But yesterday, I had no choice. This facility was the only one anywhere close, even though a forest of giant ox-eyes--see 'em?--offered passable cover in an otherwise treeless prairie.

No matter. The privy it was. When you're almost seventy, once necessity compels, choices diminish in a frenzy--you take what you get, or get to. I went in to that water-less water closet knowing it was a pit, but what's a man to do? Or woman? Not having to sit was a blessing, but being of the male persuasion means peeing into the dark soul of the abyss, which is no blessing either.

To say the least.

But, I'm a veteran, remember. "Many's the time" and all of that. I've scrubbed hundreds, thousands. Men's and women's scrubbed he them. Grit and bear it. What had to be done, had to be done.

Now there's a light switch in this one. Imagine that. If they're going to modernize, why not slip in a septic tank, right? But there's a light. Seriously. Who would want to see? But there on the wall is a switch box with a cord running up and out of the vent atop the sides of the facility.

And behind that electrical cord--a thick one--someone had stuck a gospel tract. I'm not making this up. Right there in the one-holer, there's a little sermon in print in case you're sitting there bored. Or else. . .well the possibilities are too coarse to consider.

I couldn't help it. I thought of my mother. Years ago, she bought a bale of gospel tracts and had a wonderful plan for her family, who by that time were out of the house, hither and yon. Each of us could take a pile and leave them here, there, and everywhere for people to pick up. She was a restroom specialist, too. She must have figured that what goes on right there on the thrones is thoroughly mindless activity. Gospel tracts, like the backs of cereal boxes, fill very real emptiness. Put someone on a toilet, and he/she will look for something to read. It's as natural as, well, you know. My mother would have thought that tract in that pit especially sweet.

I took it. I shouldn't have, but I did. I grabbed it and stuck it in my pocket, and now I can't find it, empty of tract and full of guilt. Somewhere in Clay County, SD, a gentleman, someone likely my age or better, is thinking that a guy never knows what kind of eternal service can be done by an evangelism tract. He leaves them in every last restroom he visits, a kind of investment.

Mom would not have appreciated the privy. She'd probably used a ton of them herself in her childhood years, I'm sure. But she would have loved that tract stuck right there behind that electrical cord, a little gospel tract advertising itself and her Lord. She'd have loved the possibilities.

Let it be known, I left that privy smiling.

Shoulda' left the tract there, however. Someday I'll return it.

Monday, September 11, 2017

Where I was on September 11*

Out here in Iowa where I live, on the eastern emerald cusp of the Great Plains, on some balmy early fall days it’s not hard to believe that we are not where we are. Warm southern breezes sweep all the way up from the Gulf, the sun smiles with a gentleness not seen since June, and the spacious sky reigns over everything in azure glory.

On exactly that kind of fall morning, I like to bring my writing classes to what I call a ghost town, Highland, Iowa, a place whose remnants still exist, eight miles west and two south of town, as they say out here on the square-cut prairie, a village that was, but is no more. Likely as not Highland fell victim to a century-old phenomenon in the farm belt, the simple fact that far more people lived out here when the land was cut into 160-acre chunks than do now, when the portions are ten times bigger.

What’s left of Highland is a stand of pines circled up around no more than twenty gravestones, and an old carved sign with hand-drawn figures detailing what was once a post-office address for some people—a Main Street composed of a couple of churches and their horse barns, a blacksmith shop, and little else. The town of Highland, Iowa, once sat at the confluence of a pair of non-descript gravel roads that still float out in four distinct directions like dusky ribbons over the undulating prairie.

I like to bring my students to Highland because what’s not there never fails to silence them. Maybe it’s the skeletal cemetery; maybe it’s the south wind’s low moan through that stand of pines, a sound you don’t hear often on the treeless Plains; maybe it’s some variant of culture shock—they stumble sleepily out of their cubicle dorm rooms and wake up suddenly in sprawling prairie spaciousness.

I’m lying. I know why they fall into psychic shock. It’s the sheer immensity of the open land that unfurls before them, the horizon only seemingly there where earth seams effortlessly into sky; it’s the vastness of rolling land William Cullen Bryant once claimed looked like an ocean stopped in time. Suddenly, they open their eyes and it seems as if there’s nothing here, and that’s what stuns them into silence. This year, on a a morning none of them will ever forget, when we stood and sat in the ditches along those gravel roads, no cars went by. We were absolutely alone—20 of us, all alone and vulnerable on a swell of prairie once called the village of Highland, surrounded by nothing but startling openness.

That’s where I was—and that’s where they were—on September 11, 2001. My class and I left for Highland at just about the moment Atta and his friends were steering the first 767 into the first World Trade Center tower, so we knew nothing about what had happened until it was over. While the rest of the world stood and watched in horror, my students and I looked over a landscape so immense only God could live there—and were silent before him.

No one can stay on a retreat forever, of course, so when we returned to the college we heard the news. Who didn’t? All over campus, TVs blared.

But I like to think that maybe my students were best prepared for the horror of that morning not by our having been warned, but by our having been awed.

Every year it’s a joy to sit out there and try to describe the character of the seemingly eternal prairie, but this year our being there on September 11, I’m convinced, was a blessing.

______________________

*Reprinted frequently on September 11.

Sunday, September 10, 2017

Sunday Morning Meds--Goosebumps

“Praise the LORD.

How good it is to sing praises to our God,

how pleasant and fitting to praise

him!” Psalm 149:1

I remember a certain species of goosebumps, my first. I was twelve maybe, part of a choir festival

a half century ago in a small town in Wisconsin, hundreds of kids drawn from a

dozen Christian schools. The music was Bach—“Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring.” For almost fifty years I’ve not been able to

hear that piece without remembering that day.

My entire self—heart, soul, mind, and strength—reacted to the beauty of

the moment.

They arrived in an afternoon rehearsal before the big

concert at night—I remember that. I

remember what that gymnasium looked like, which step I occupied on the

bleachers, and some of the kids around me; and I remember being embarrassed

because this unmanly tearful impulse—which I loved anyway—was still a threat

that required testosterone to obstruct.

The music was gorgeous. But my girlfriend was there, and I

haven’t forgotten that either. She stood

a row or two beneath me in the choir, and her being there was part of this odd

emotional seizure, an almost synesthesia-like moment. I don’t know that the music alone would have

raised so much viscerally. My seeing

her, a row or two beneath me was part of the moment too.

And faith was part of it—we were singing about Jesus, and we

were all kids from Christian schools. Add that to the beautiful music—we

couldn’t do much better than J. S. Bach and my girlfriend—most of us experience

love long before we can define it, don’t you think? I was feeling myself a part

of something so much bigger than myself; that had to play a role as well—all

these kids were making a beautiful, joyful noise.

First thing out of the box, Psalm 147 says how pleasant it

is praise him, how pleasant. It’s an almost shockingly human assertion: “praising

God feels good.” The first declaration

of this psalm has nothing to do with our duty (“we should praise him”) or his wanting our praise. Instead, the psalm

starts with the me: O, Lord, it feels so good. And it’s fitting

too.

I wonder whether my skin turned inside out and tears threatened

because, maybe for the first time, my “self” almost disappeared. I felt lost in the beauty of the music, lost

in affection, lost in the joyful affirmation of group love that is choral

music, lost in all those things, just lost.

Selflessness is a good thing. Love is selfless. Heroism is selfless. Vivid spiritual experience is selfless. When

Mariane Pearl heard of her husband Danny’s brutal death at the

hands of terrorists, you may remember, she said she was able to handle it because she’d been

chanting. She’s Hindu. “The real benefit of having practiced and chanted was

that at that moment was that I was so clear on what was going on. This is a

time when I didn’t think about myself at all,” she told reporters.

Sometimes it’s just good to lose yourself. It’s good to praise, to give yourself to

God. It’s good to love, to give yourself

away. Praise—whether it’s evoked by a Bach chorale or bright new dawn—gives us

a chance to empty ourselves. Faith does that. It can.

And that’s good, I think, and it’s pleasant, I know, and

it’s fitting before the King, our King, who is, after all, “the joy of man’s

desiring.”

Friday, September 08, 2017

Blessings!

My wife, who has banked sufficient experience to know, claims her husband is downright intolerant about standing in lines. She's right. If we're bound to a particular restaurant, and the space outside is already SRO with eager diners, I'll suggest Culvers. I hate waiting.

Pictures out of Florida right now trigger horrors. The lines yesterday around Floridian Costcos were endless, freeways north bumper-to-bumper. Everything is choked. Gas is gold.

It would be comforting to believe that time is standing still, but it isn't. Irma is coming soon. "The winds and waves obey Him," we used to sing in Christian school. Sweet testimony, but Irma's winds and waves? Really? That's a whole different kind of faith.

The videos picture sheer madness, as a half million Floridians--east coast and west--need to form a single lane to get up and out of the peninsula. Irma is wider than the 160 miles from one side to the other. Millions have become kindergartners--"Okay, kids, now--get in line." Only they're not kids--they're frantic adults, and they have to be frightened because what Irma has already left in its wake is almost total devastation, one island after another.

Texas?--who remembers just last week? An entire country's devoted attention is on Florida right now because weathermen and women, real meteorologists, scientists, are throwing up their hands--"No one's ever seen anything like it." In Florida, it looks for all the world as if this is the big one, just as it did in Texas last week.

President Trump shocked pols everywhere by sidling up to Chuck Schumer and Nancy Pelosi, a totally unexpected shift conservatives considered akin to signing a pact with Mr. and Mrs. Satan. It's not easy for me to be sympathetic with this President, but you can't help but guess that Trump wasn't thinking about politics but catastrophes. It's entirely possible that Miami will be inundated, just as Houston was, that the price tag for rebuilding will be beyond anyone's imagination. Ain't no time for games. Things have to be done.

In the great dust storms of the Dirty Thirties, good Christian people began to think the black sky signaled "end times," Judgment Day had come. It wouldn't be long and the trumpets would sound.

Harvey and Irma--sounds like a cartoon--shake that fear free again. Two huge chunks of the American populace find themselves in madness going off the charts. Some will certainly believe the end is near.

It's all horrifying. This morning I'm thankful to be here and safe and out of those long, long lines; but I'm also thankful for the battalions of heroes who have and will selflessly help those less able, those who risk their lives for others, those who already have--and died.

Those two storms are anything but cartoons. They have and will alter the lands they will rule for a time.

In Texas, I'm guessing, the sun is shining again, as it will soon in Florida. That it's not end times doesn't mean there's an end to the need for prayer.

Thursday, September 07, 2017

Small Wonders--Educational Theory, 1878

If you can take I-90, west, most people think you’d be downright crazy taking Highway 18, a meandering two-lane-r that slows through small towns you’d never otherwise notice. Highway 18 barely deserves the word highway.

But if you’re crazy enough to wander and you have the time, you could do worse than score a big sky sunset some late afternoon over Hwy. 18. It’ll take you through endless reservation lands, two of them—the Rosebud and Pine Ridge—side by side in the lower echelon of west river South Dakota counties.

The town of Mission may be the heart of the Rosebud, a town where you can’t miss signs for Sinte Gleska University, a four-year tribal college enrolling somewhere close to a thousand students.

Sinte Gleska is the Lakota name of the man considered a tribal George Washington, a long-gone chief whose name translates as “Spotted Tail.” If you know anything about him, you can’t help but think memorializing him is a good choice—a wise one--for the Rosebud school.

And, you’re right, there is a story there, a story about an education.

In 1878, just two years after Little Big Horn, Spotted Tail listened to a spirited sales job by Col. Richard Henry Pratt, a Civil War and Indian wars veteran, who devised a plan for Native education. Pratt’s new school would “kill the Indian to save the man,” or so he promised, which made Carlisle Indian School, an institute of acculturation.

Col. Pratt told Spotted Tail that what Native people had suffered could have been avoided if the Lakota could read the treaties they signed. Send your kids to Carlisle, he said, and they’ll learn to read the write the English language.

Pratt’s recruiting trip down Hwy 18 that summer was less successful at Pine Ridge than it was on the Rosebud, where Spotted Tail surprised everyone by sending five of his kids way out east to Pennsylvania.

But “out east” wasn’t a foreign land to Spotted Tail. He’d spent a couple years imprisoned out east, because he’d sacrificed his freedom for a kid who’d murdered someone, gave himself to the law instead of turning in the guilty. Spotted Tail was, by all accounts, that kind of good man—and an easy man to like. He was trusted while incarcerated, not under lock and key.

“Out east” he couldn’t help note how many white people lived in endless cities and towns. Their sheer numbers convinced him it was fruitless for Lakota warriors to fight. In a difficult season of radical cultural change every Native man and woman faced, Spotted Tail determined that if his children learned to read and write English, life might get easier.

So the kids got on the train and went out east. When, later, he was told that way out there in Pennsylvania, his children got themselves baptized, he was furious. Induction into the white man’s religion wasn’t in the contract. He had no intention of turning his children into imitation white kids.

Because he’d been one of the first to signal his participation in Pratt’s Carlisle School, Spotted Tail was an instant celebrity when he got off the train in Pennsylvania for a visit. Pratt fawned over him, and a cotillion of sweet and well-meaning Quaker ladies insisted on having their pictures taken with the great pagan Lakota war chief.

But that adulation played only short-term. Once Spotted Tail talked with miserable and homesick kids in short-cropped hair and tight shoes beneath those awful white man’s clothes, he blew up. The handsome headman, known for his congenial nature, blasted Pratt right there in front of everyone, the Quaker ladies, Carlisle’s well-heeled donors, and most of the student body. Then Red Cloud, Two Strike, Red Dog, and American Horse, who’d come with, all let Pratt have it too. Besides, Sinte Gleska said, none of the kids had learned much English.

It must have been ugly.

Or beautiful. You choose.

Spotted Tail corralled his progeny right then and there, and let them know they were leaving, post-haste—as did that council of chiefs with him. He wanted his kids to learn English, not become English. He wanted his kids to grow up Lakota.

Go ahead and take Hwy. 18 west someday and spot those signs along the road on the Rosebud, step out somewhere in the country and think of a strong Lakota headman shepherding his kids onto a train and taking them back to where they came from, the very earth beneath your feet.

Wednesday, September 06, 2017

Book Review--The Boys in the Bunkhouse

Willie Levi complained one day about a pain in his leg, in his knee, complained to his supervisor at the packing plant where Willie shackled live turkeys, upside down, into hangers that would carry them to the kill floor. Willie Levi told his super that his leg hurt, hurt bad, but the super told him to keep working because he wouldn’t have Willie slacking off, so he followed orders, kept working, kept on and kept on, just as he had for years, for decades.

Willie Levi is a looming presence in Dan Barry’s Boys in the Bunkhouse; he's a man gifted to talk to turkeys, a “turkey whisperer,” Barry calls him, because something in his voice calmed those birds as he delivered them to their deaths.

But Willie hurt his knee, he said, so when the whole story broke—how several dozen developmentally disabled adult men from Texas were working for scratch in an Iowa turkey plant, living in unimaginable filth, the social workers who freed Willie and his friends from the grievous exploitation they’d suffered asked him if he had any medical problems. Willie pointed at his leg, said it hurt. Immediately, someone took him to an urgent care facility in nearby Muscatine, where the diagnosis was simple but painful—Willie Levi had a broken kneecap he’d lived and worked with for far too long.

That Willie Levi story is one of hundreds New York Times reporter Dan Barry relates in a heart-rending compendium of stories, all of them concerning the “boys,” a bus full of men sent up north to Iowa from Texas to work packing plant jobs no one reading these words would do, men intellectually disabled, who lived in squalor unimaginable in rural Iowa.

Countless characters people these stories, not simply “the boys from the bunkhouse” either, although most of them, like Willie, are here. There are heroes, men and women—reporters and social workers—who went out of their way to free the men from their 21st century slavery. Some you'll meet are heroes, some are certainly not. Some didn’t care, didn’t act, kept their mouth shut when they should have spoken.

But there are no snarling villains. Dan Barry’s marvelous reporting doesn’t indict the plant or Louis Rich, doesn’t even damn T. H. Johnson, the Texas entrepreneur once universally applauded for creating jobs for men thought otherwise unemployable. For some time, what Johnson was up to created sterling benefits for the boys—jobs, spending money, a place in life.

Neither does Barry lay a glove on Atalissa, the tiny dying Iowa town where people brought the boys into their love and care, danced with them and gave them a place in town celebrations, took them to church.

The story is surprising in many ways. You’ll be amazed at what Atalissa gave, but saddened to realize that all that giving was never enough. The Boys in the Bunkhouse is not simply an indictment of the horrors of life on a kill floor or some broadside against rural provincialism; its primary concern is examining our own longstanding instinct to look past people we’d rather not see.

The Boys in the Bunkhouse: Servitude and Salvation in the Heartland is a marvelous read. When you close the cover and put it down, it won't simply stay on the shelf; it's a sad reminder of Jesus's words that “the poor you have with you always.”

Nations and cultures can be judged, a friend of mine used to say, not by their GNP, but by how compassionately they care for their own less fortunate. Dan Barry’s wonderful book is a moving reminder of something so sadly easy to forget—what it really should mean to be human.

The Boys in the Bunkhouse is this year’s Sioux County’s "One Book, One County" selection.

The story is surprising in many ways. You’ll be amazed at what Atalissa gave, but saddened to realize that all that giving was never enough. The Boys in the Bunkhouse is not simply an indictment of the horrors of life on a kill floor or some broadside against rural provincialism; its primary concern is examining our own longstanding instinct to look past people we’d rather not see.

The Boys in the Bunkhouse: Servitude and Salvation in the Heartland is a marvelous read. When you close the cover and put it down, it won't simply stay on the shelf; it's a sad reminder of Jesus's words that “the poor you have with you always.”

Nations and cultures can be judged, a friend of mine used to say, not by their GNP, but by how compassionately they care for their own less fortunate. Dan Barry’s wonderful book is a moving reminder of something so sadly easy to forget—what it really should mean to be human.

The Boys in the Bunkhouse is this year’s Sioux County’s "One Book, One County" selection.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)