What a couple dozen Santee families took home from the Ft. Laramie Treaty was not anger that grew from resolve never to give in to the white man. The Native leaders we honor--Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse--after the Fort Laramie tend to be those who, in the spirit of New Hampshire, "Live free or die."

In the Great Plains, Ian Frazier worships Crazy Horse, the Lakota warrior who wouldn't be photographed, wouldn't become an "agency Indian," wouldn't do anything white people wanted or demanded him to. We honor Crazy Horse with good reason. He was a fighter, wanted nothing less than justice for his people. He wasn't interested in conquering the hoardes of white folks streaming west and homesteading all over Sioux land. He wanted no more or less than to live as his ancestors had.

But in On the Rez, Frazier says he's walking some things back from the honors he gave Crazy Horse. In On the Rez, Frazier claims Red Cloud should stand as high Crazy Horse in our esteem, even higher perhaps because Red Cloud came to understand when making war creating little more than more death among his people.

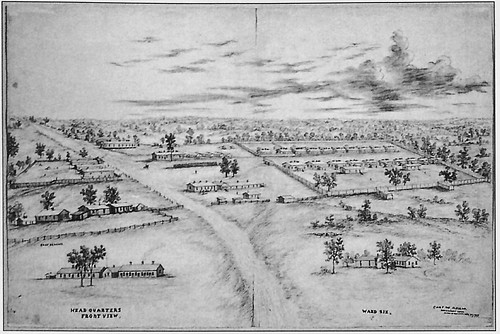

The Santees who left their Nebraska reservation in early spring of 1869, determined there had to better way of life than what they would experience on their newly created reservation. So they walked to a place forty miles north from what became Sioux Falls, South Dakota, at just about this time of year. The weather here can change in an hour. Saturday morning it felt like spring. Sunday morning it was winter. Walking 150 miles was not unusual for them, but when a blizzard came, their numbers were decreased by one--a woman died. More left Nebraska later that year; more again the next.

They were leaving behind the guarantee of annuities, the reparations the government promised if the Sioux people pledged never again to take arms against the flood of white folks moving west.

In lieu of all sums of money or other annuities provided to be paid to the Indians herein named under any treaty or treaties heretofore made, the United States agrees to deliver at the agency house on the reservation herein named, on or before the first day of August of each year, for thirty years, the following articles, to wit:

For each male person over 14 years of age, a suit of good substantial woollen clothing, consisting of coat, pantaloons, flannel shirt, hat, and a pair of home-made socks.

For each female over 12 years of age, a flannel shirt, or the goods necessary to make it, a pair of woollen hose, 12 yards of calico, and 12 yards of cotton domestics.

For the boys and girls under the ages named, such flannel and cotton goods as may be needed to make each a suit as aforesaid, together with a pair of woollen hose for each.

The Treaty mandated much more, of course, including the promise of individual land ownership within the reservations. But when the Santees left their Nebraska reservation and started walking north, they had determined not to be wards of the government.

Why risk leaving? Why turn down what the government promised?

The germs of this movement are to be found in the resolves for a new life made by these men when in prison. They were all nominally, and the greater number of them really, converted to Christ. All of them, in some sense, experience a conversion of thought and purpose.That's how Reverend Stephen R. Riggs explains their motivation to leave in his mission memoir Mary and I: Forty Years with the Sioux. To be sure, he has good reason to assess their leaving the way he does--he is undoubtedly determined to register successes among those to whom he ministered. He wants to believe his lifetime of mission work bore fruit.

But what if he's right? What if the desire for freedom in those Santee families grew from a growing unease with a way of life that they perceived might well become a endless circle of dependency? What if their Christianity helped them determine that they wanted to live free, as citizens of the nation? Then isn't it worth our time to know that when we pass the old church on the hill just outside of Flandreau, South Dakota?--a church and a community established by Indians, not by white men,

Here's how Rev. John Williamson saw it:

Many wonder why the Flandreau Indians ever left the agency with free rations and gray suits. If one could see into their hearts, he would find that it was the same longing to "be one's own," or for freedom, as we say, which led the Puritans to Plymouth Rock.Once upon a time, the novelist Frederick Manfred told me where his interest in regional history began. His father and the boys had just finished milking, he said, so he sat down on the cement steps outside their farm house near Doon, Iowa, and looked out on the broad land before him, miles of it. He said he couldn't help asking himself what stories were there in and on that land, stories he knew nothing of. There had to be more than he knew, he told himself.

That's where the stories began.

Sometime soon, sit on the step and wonder for yourself. I'll have you know that the River Bend Church isn't all that far from here, just a ways north. Worth the trip. Oldest Continuously Used Church in South Dakota. Read the sign for yourself someday.

It's not that far from home.