Very little of the great Missouri River looks as it did when Standing Bear and his Ponca band lived out there at the confluence of the “the Big Muddy” and the Niobrara. Four huge dams brought discipline to a madcap river once far too unruly. People say the segment most akin the Missouri Lewis and Clark navigated is right there—from the mouth of the Niobrara south to Yankton.

From its broad shoulders on both sides, the view is breathtaking. If you cross Standing Bear Memorial Bridge into South Dakota, by all means pull over; there’s a rest stop. Get out of the car and have a look for yourself, but take a good long breath when you put your feet on the ground because it may be a while before you can breathe again.

Those giant sandstone cliffs, like a long succession of clenched fists, make the wide valley almost cavern-like. All around, the land rolls, rises and falls as if a millennium ago some Great Spirit shook out a blanket.

Just don’t be fooled by the landscape’s stunning elegance. You're in a rugged place whose beauty belies its unforgiving seasons. A cadre of Mormons tried to winter right there in 1847, and had to leave their dead behind, a tally that would have grown had the Poncas not come to their aid and helped hustle them out, come spring. A monument stands there in remembrance.

Winters are brutal, summers stifle, and buffeting winds threaten in every season to blow you away. But it’s a beautiful world right there at two rivers. If you get up high in Niobrara State Park, it’s easy to see why Standing Bear walked all the way from eastern Oklahoma to be here, to be home.

You can question folks in town, but there’s only one answer to the question you won’t be the first to ask: No, no one knows where Bear Shield was buried, once Standing Bear, an actual, legal person by court decree, came back to the neighborhood. You may ask, but I’ll tell you the answer to your next question, too: No, no one knows where to find the grave of Standing Bear either.

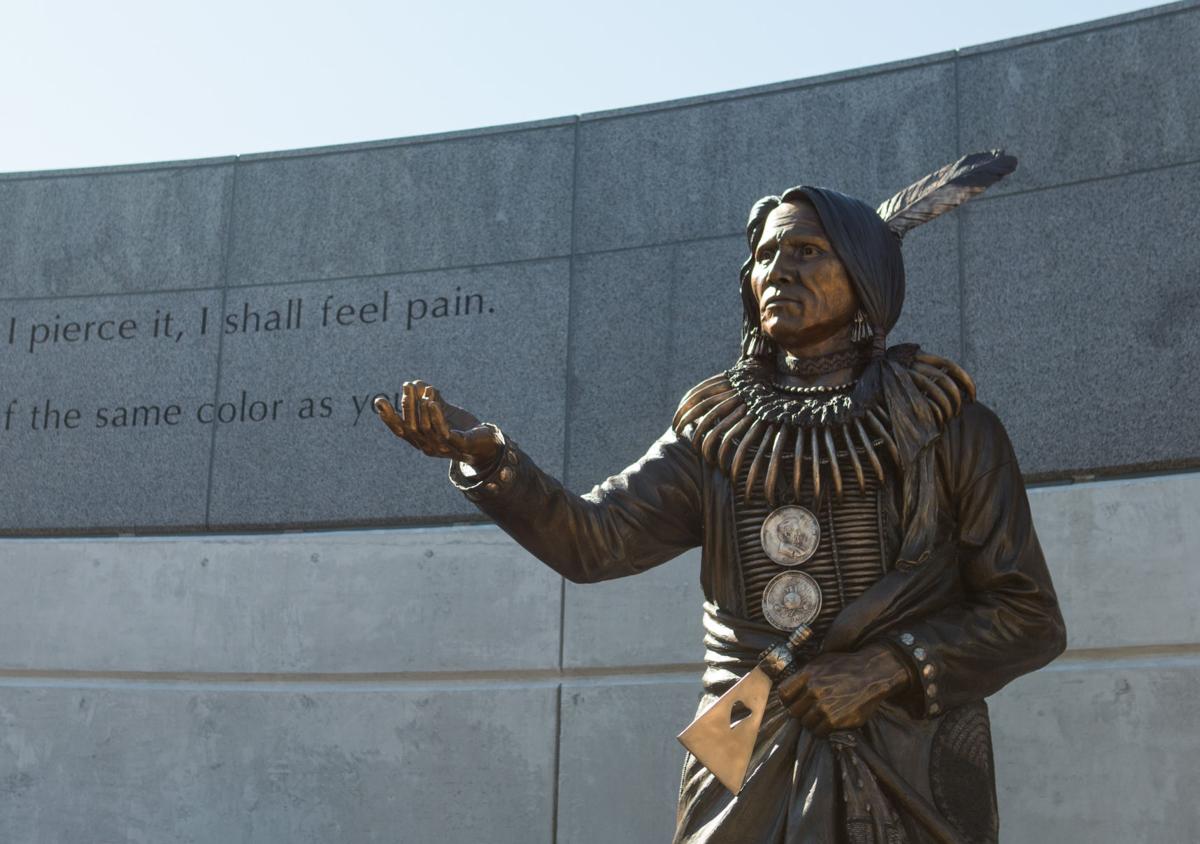

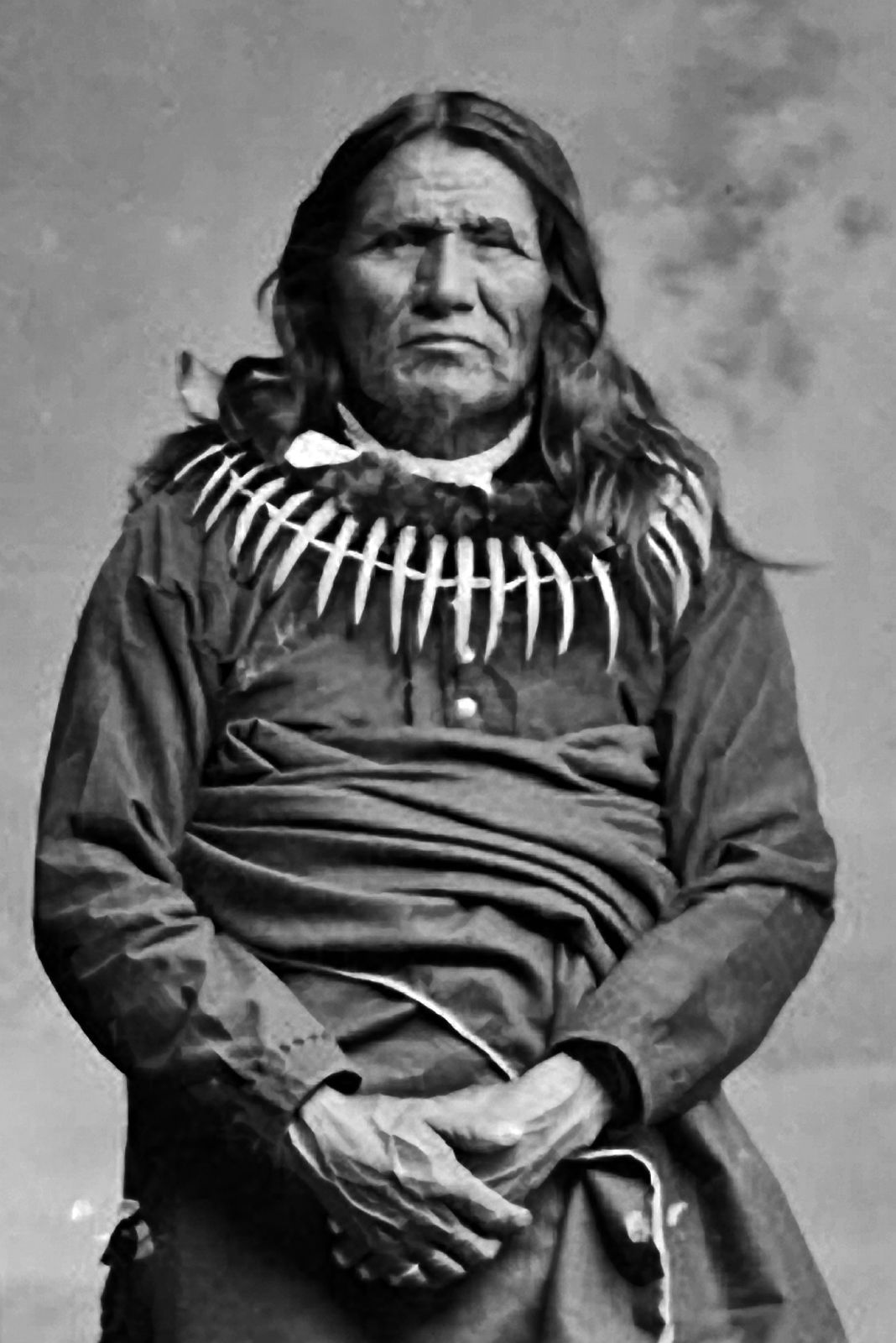

That’s okay. Leave town, drive west, don’t be afraid of getting off the highway. Get up on one of those hills and sit there for a while, because he’s still around dressed in that bear claw necklace. But his weariness is gone now. He's at home amid burgeoning hills delicately threaded by ribbons of rivers all around. You can look for a gravestone, but, if you’re quiet and if you wait, if you simply sit there, I swear you’ll see him in his world.

There is a graveyard. It’s not marked, but if you follow a winding road for a mile or so farther than you might think comfortable, you’ll come to a gravel intersection at the foot of a cemetery that runs up to the top of a steep hill. The stones in that graveyard sit in bands, not rows. One of Standing Bear’s headmen, Buffalo Chip is there, not far from where you’ll park. "Chief of the Ponca Indians," his stone says. Some graves memorialize men and women who claim to be grandchildren and great-grandchildren of Standing Bear. You’ll be as sure as I was that these are the graves of Standing Bear’s people.

Not all the stones and sites are old. People still want to be buried there, in a spot behind a sign that spells the tribal name with a K—PONKA CEMETERY. A sign that stands over a rutted driveway where occasionally a burdened hearse must still come in to navigate that steep hill.

Some of the most recent graves are set up at the top, at the far end of property. It’s worth the long walk to get up there. Besides, far away on the other side, someone keeps buffalo. If you’re lucky—if you’re blessed—you’ll see them. They may well seem a vision. They’re very real, but visions lie all around. Think what you will.

Skeptical? Sure. Look, by white man’s standards, the place isn’t kept. Somebody ought to mow the grass. And all that clutter around the graves?—it should be out of there a week after Memorial Day. It’s a mess. And it's steep: if you want to ride to the top, you better have four-wheel drive.

Soon enough, there will be another delegation of Native folks here, laying to rest the remains and the funerary items of aboriginal people who were here at the time of the First Thanksgiving, and before. They’ll rest, in state, here, among Standing Bear’s Poncas. And, thanks to him, they'll rest here as persons, not museum specimens.

You'll find no grave up on the hill, but this you're in the place where Bear Shield, just a boy, 16 years old, told his father he wanted so badly to be buried. This is the home of Standing Bear.