Morning Thanks

Garrison Keillor once said we'd all be better off if we all started the day by giving thanks for just one thing. I'll try.

Wednesday, January 30, 2019

On a Sabbath morning--ii

As near as I can tell by old maps and surveys, this is the 80 acres Niklaas Vandervelde at one time long ago called his own. It's where he put up his soddie or lean-to, or where, with the help of friends, he nailed together a 14 x 14 frame palace. Somewhere here, he and his wife and six children pulled off a ragged trail and staked out a claim. They wanted to put down roots on the Nebraska prairie, following the way west to opportunity.

That picture is deceiving. There's a line of cottonwoods in the draw that would not have been there. his neighbor's letters describe the region as all grassland back then, endless miles of it, which made for monster fires.

Raging prairie fires are long gone now. They can still roar farther south, where the land isn't worked but pastured. In Kansas and Oklahoma, grass fires still consume livelihoods and even people. But here in Lancaster County, where once three girls died in a holocaust of flame, a repetition of that tragedy is unlikely.

I couldn't help stopping by. Vandervelde's land is off the beaten path, and there's no historical marker, no sign, not notice of that horrifying long-ago moment in community history, the day an immigrant farmer and his wife, strangers in a strange land, walked out of church and into their own kind of hell. It was 1871. There likely weren't any cemeteries. Who knows where the girls are buried? No one.

I stopped in town at the church that grew out of the immigrant settlement all around, a handsome building in a small town that looked a great deal like many Great Plains hamlets, as if maybe it needed some support to be able to hang on. I may be wrong. Perhaps Firth, Nebraska, is close enough to Lincoln to bulge into a suburb someday. It's undoubtedly a bedroom community already.

But the church looks to be doing well. Not long ago, they celebrated their centennial, but I doubt anyone remembered to note the prairie fire that killed three young women 150 years ago. There may not have been a church in town back then. In 1871, there may have been little more than a post office. When Vandervelde and his vrouw walked out of church that morning, church may well have been a neighbor's sod house.

When the Dutch townships of Lancaster County were first settled, a good deal more people were here on the land. Most homestead were 80-acres, which meant more families lived out here, and the families were bigger--much bigger. Firth may not have been much of a town back then, but the rural community out here was larger.

For years, people couldn't--and wouldn't--forget the prairie fire that consumed so much all around and killed three young Vandervelde girls. It was story told in whispers from one generation to another until, I suppose, it simply lost currency. "Vanderveldes?" people might say. "I don't know that name." Like so many others, the family sold that 80 to neighbors and then left, living up to their name's meaing--vandevelde: "from the fields."

I thought I'd go find the land where those three Vandervelde girls died in a hellish prairie fire. The story stuck with me with such tenacity that I figured I owed that much at least--I needed to pay my respects.

A friend of mine who's Cherokee insists that if you sit somewhere close to where such things happened, things like death in a prairie fire on a clear Sabbath morning, if you just sit there and look and listen long enough, you'll hear those voices in the wind.

There was a time I thought that was silly.

Things couldn't be more different out there on the prairie when I visited. It was cold and snowy, dreary and January gray. There's a tree line, behind it a corn field. The sea of grass in Lancaster County is no longer. The Vanderveldes and much of the homestead community that once existed right here is gone. What you see up there in that picture is nothing at all close to what the man saw that day coming out of a sodhouse church.

But still, today, even in the cold, if you wait and listen, it's like my friend says: you may just hear voices in the wind.

Tuesday, January 29, 2019

On a Sabbath morning--i

Sunday, October 15, we went to church. The wind was then blowing wildly, but this became worse further along in the day. When we got out of church we saw smoke in the distance, because the prairie was on fire.It is November, 1871, and Harmen Jan te Selle, an immigrant homesteader from Lancaster County, Nebraska, is writing home, to the old country, to "Much beloved Mother, Brothers with wives and children," writing them from a sod house amid grasslands he knows his family back home could not have imagined because he himself could not have imagined the immense, roiling sea of grass he was trying to call home.

All that grass, he tells them, "is still unoccupied." He might have well have said "untamed." He knows he's among those who are trying to do just that, which is part of the reason te Selle's letter home begins with a record of their harvest: "First of all, what concerns us is the crops. It is this year quite good." Then the particulars: "Corn is very good; of this we should, I believe, have 800 or 900 bushels," which is to say, things go well in America.

Not until the end of the letter does he tell the story of the prairie fire. When the grass is high and dry, he says, "it can stir up a big blaze." They have no idea. Neither did he until he saw it with his own eyes. "It can burn for miles away," unimaginable miles all around. For him, Nebraska is unimaginably huge. "When the grass is gone, then the ground is bald. The soil does not burn."

He's probably sitting in a sod house, a lamp beside him as he tries to determine how to relate horror. "So I wanted to say," he says, almost as if he's lost track of the story. He hasn't. What he needs to say is difficult.

"So what I wanted to say, that when we got out of church, we saw the fire," the kind of fire, remember, that "can burn for miles away." The story must be told.

A man, named Niklaas VanderVelde saw that the fire was not far from his house. He was in church with his wife and two children. Three children were at home; a girl of 11 or 12 years, one of 8 and the other of 5 or 6. So he ran as quickly as he could to reach home, but what did he see? His house lay entirely in ashes.Nothing could have prepared Harmen te Selle for what happened that Sabbath morning in a prairie fire he and his fellowship of immigrant homesteaders discovered to be a holocaust. Things burned for miles around.

"High standing grain and 4 pigs were all burned, but not the worst," he writes, still hedging, still trying to determine how tell his loved ones what they'd all witnessed after worship in the endless grasslands.

He saw in the distance something white lying on the ground, thinking it was a calf. But when he got closer he saw it was his oldest girl lying burned on the ground, and upon investigation, the other two were in the house, entirely burned. Thus a tragic situation for that man.All of this tragedy narrated at the end of the letter. "Also," he tells his old country family, " there were some more misfortunes caused by that fire, and at many other places. There were big fires and many fields entirely burned down," he says.

And then this: "Beloved, the paper is too small to write more." And then "Greetings from us all."

It's difficult for me to imagine that Harmen teSelle didn't sit there for a moment and read through that letter, this time picturing his "Mother, Brothers with wives and children" sitting and standing all around in a house he knew so well he could have painted it--everything, even the wall hangings. That last time through the letter, he watched them read the story he'd told, saw their eyes and read their silence. And then, "Write soon again," he added at the bottom, to remind them.

I'm guessing he put that letter of his down, took a breath or two, prayers really, and went out to the lean-to to milk and do chores. Still shaken and humbled in that vast sea of grass and the scorched fields all around, he returned to what he knew had to be done, as somehow all of us do.

Monday, January 28, 2019

Collected Stories

Somewhere among the thousand-or-more books I own, books stashed in three or four places at home and office is The Collected Stories of Collette. I don't think I've ever cracked its bindings, but I remember buying it decades ago, in part because I knew at least this much about Collette--she was a scandal. Not much more.

The cover art suggested the very real possibility of some steamy reading--that was cause, I know. And I was, at the time, trying to increase the size of my library of short story collections. It was at a time when I wanted to know everything--every important writer. I actually remember buying that book, in part because I remember the cover, remember the impulse, which was neither righteous nor something I'm celebrating. But I never read it, and the book is still there, I think, on a shelf full of short story collections.

What do I know of Collette? Not a whole lot more than I ever did, and, of course, barely a thing about her fiction. Constancy--commitment--was not her forte. She married and remarried as if the institution was actually a revolving door, spicing up her life on more than one occasion with fairly well-publicized trysts with lady friends. She wrote fiction and poetry; some French literati considered her their finest writer in the early years of the 20th century.

She was, in other words, a presence in the world's finest literature of the time--and since, I imagine. I'm sure one could find a dozen or so dissertations on her and her work just this year. I have no idea how her books sell anymore.

During World War II, she hid her husband, a Jew, in the attic of her home during the entire Nazi occupation of France. She lived the kind of glossy life upon which gossip rags make their livings. For decades, in Paris, she had to have been all the rage.

But I never opened the book. And now it's time for me to downsize. One of my jobs in the next few years is going to be to get rid of that massive library. I won't have much trouble with Collette. Although she still has her disciples, I'm sure, I'm not among them. Honestly, I don't know her.

Today, the Writer's Almanac says it's her birthday: ". . . the novelist Colette, (books by this author) born in Saint-Sauveur-en-Puisaye in the Burgundy region of France (1873). She is best known as the author of Chéri (1920) and Gigi (1945)."

And then this: She said, "What a wonderful life I've had! I only wish I'd realized it sooner."

The Collected Stories of Collette is a brick, really, and the likelihood of my reading it before my office gets scrubbed is pretty slim. To see it again this morning reminds me of what were once my dreams, my professional dreams, of what I wanted to be, where I once wanted to see myself.

And now I just have to giggle, because the only words I'll likely ever read of this early 20th century French writer, someone who left just as many lovers in her wake as scandals, is two short sentences I just now heard for the first time, wisdom that could well come from Proverbs: "What a wonderful life I've had! I only wish I'd realized it sooner."

From Collette. Then again, Solomon was no paragon of virtue either, come to think of it.

No matter. "What a wonderful life I've had! I only wish I'd realized it sooner."

Thanks, tart.

Sunday, January 27, 2019

Sunday Morning Meds--"A Should Thing"

“Offer right sacrifices and trust in the Lord.” Psalm 4

My wife and I have developed our own language. If I say—as I did last night—that tonight I’d be going to a “should thing,” what both of us know I mean is that I really don’t want to. I’d prefer to stay home or sit out on some hill all by my lonesome. But I’m not. I’m going. It’s a “should thing.”

What both of us know is that, in life, often as not, we have to do things we’d rather not. We do them because we should. In the Christian’s life “should things” compel us much more often than they do, I’d guess, in a life that isn’t entangled in the commitments that rise from church and school and what not else with a halo.

Is it good for me—doing a whole raft of “should things?” Wouldn’t I be better off emotionally if I didn’t get collared by responsibilities that, with just a little tweaking, might well be seen as, well, appearances anyway? “I really should be there,” I say sometimes. Can conscience ever be a burden? Don’t all of us want to flip off the world once in a while and go our own way? I sure do. Don’t tell anybody, but often as not we get downright sick and tired of “should things.”

Of course, I choose to live in a small community, where what it costs to flip off the world is nothing to sneeze at. Where’s there’s no anonymity, there’s more responsibility, or so it seems to me. My wife and I live in a virtual Wal-Mart of “should things.” Just about every blasted night there are “should things.” Maybe I’m overstating.

King David’s twelve-step program in Psalm 4 continues in verse five with a couple of “should things”: “offer right sacrifices and trust in the Lord.”

Honestly, I don’t have much trouble with the trusting, but his first command strikes me as a “should thing.” It shouldn’t, but it does. Which is another conundrum, I guess, isn’t it?

If you want to get answers to prayers, David says, here’s a list of things to do; one of them is offer “right sacrifices.” It’s not even a matter of should here, it’s a matter of must. Sacrifice. Give of yourself. Echelons of therapists be hanged, if you want to sleep well (which is, in a way, what Psalm 4 is about), there simply are things you should do.

I remember reading Abraham Kuyper’s suggestions for “should things.” He advised that if we really wanted to be near unto God we should act like him: we should forgive, we should love unconditionally, we should seek the best for others, we should sacrifice. You’ll know him best by doing what he does—that’s what Kuyper suggests. It made sense when I read it, and it makes sense today when I think it through. But oh, my goodness, what a multitude of “should things.” And they’re all so demanding, so tough.

Yes, my dear, there are “should things.” And yes, me, we ought to do them. Some should things are really must things.

And we’ve certainly got this much up on David, the poet king. We know darn well that some massively important things were done deliberately for us—and those events weren’t “should things” either. Start here: a cross, a death, a trip to hellishness.

Thanks be to God. Thanks be to God. Thanks be to God.

Friday, January 25, 2019

No Heart of the Ioways

Had I gone to school in Iowa, perhaps I'd have known this guy, a headman named No Heart; after all, his people left their name behind when they went west and south. We're Iowans because of him--and them. But his descendants are a proud people, who live in Oklahoma, just outside of the town where my son's family lives, just across the Cimarron River.

When most white folks think of Native Americans, they think of a string of Lakota warriors in feathered headdresses, here and there a bear tooth necklace maybe, a gang of killers wielding bows or a Winchester, a fur shawl thrown over a shoulder, all of them riding paint ponies up atop the next grassy hill.

White folks think of fights and raids and fierce, devilish screaming, somebody butchering somebody else. The frontier is now more than a century behind us now, and what's left--the detritus of all of that history--is a collection of images that may well belong more identifiably to Hollywood than to history.

The Ioways don't fit the mold. No Heart may have distinguished himself for bravery, as the sign beneath his impressive statue maintains, but he did his fighting against his long-time foes, the Sauk and the Fox from the east, and the Dakota from the west, tribes who almost always outnumbered his. And against a host of illegal immigrants who simply pushed the Ioways out of their way.

Historically, the Iowa people were farmers until Europeans pushed them west into a semi-nomadic way of life more typical of traditional plains Indians. Their artifacts show up first in the Great Lakes region, but they move to Siouxland, along the Big Sioux and out to Okoboji, setting up shop around Pipestone's red stone quarries. In 1804, Lewis and Clark parleyed with them at Council Bluffs. For most of the 18th century and on into the 19th, what we call Iowa was their home, all four corners.

That land was ceded to the government in 1824, then again in 1836 and 1838, and the tribe was given a reservation in Kansas, just ten miles wide and twenty miles long. If there was a "long walk" for the Ioways, a "Trail of Tears," it's not recorded, perhaps because their ranks had been so depleted (there were less than a thousand already when Lewis and Clark met them) that they were too often too easily raided and thus looked toward Kansas and eventually Oklahoma reservations as safe zones.

To say the Ioways wanted to go to Indian Territory is dead wrong. For them, as with other smaller, less war-like tribes, Indian Territory (Oklahoma) was at least something of a safe haven.

All of which means that No Heart's bravery--as the sign says--may well have less to do with outright, bloody warfare than with the kind of negotiations he did for his people with the white folks whose ever-increasing presence made traditional tribal life impossible. There are, after all, more ways to maim a people than bloody warfare.

Just happened to run into No Heart yesterday--a strikingly proud figure--while I was being jerked along by a rambunctious five-pound Pomeranian. No Heart's presence is daunting, but his story--and the story of his people who left their name across an entire state--is more complex than Hollywood--or most of us--can handle.

Greeted him here just yesterday here, a fellow Iowan, in Perkins, Oklahoma, his people's home. Made me proud.

Thursday, January 24, 2019

The End of the World in Ireton--iii

Jake and Betts have their granddaughter, Shelley, a high-schooler, overnight. Shelley has a test, mentions Orson Welles, and Jake can't help but tell her what happened the night the world ended in Ireton.

____________________

“I don’t remember exactly what we got shooed out of church," Jake told Shelley. "We just hung out around town for a while. What’d we do, Betts? We spent a hour or two doing nothing.”

Betts could feel a blush coming on. “We went out in the country, west of town—you and I, and Henk and Faye, because Henk had the car.”

“That’s right. We went out by the old Vander Berg place. It was deserted by then already, and we sat in the yard and watched the sky, lookin', you know--searchin'. We thought maybe we’d see some shiny spaceship coming down to take over—”

"I'd'a' been scared," Shelley said. "And you didn't have internet."

"Nothing but the word of the preacher that it was end times," Jake said, giggling. "Right then and there it was end times."

“Oh, you guys laughed and laughed,” Betts said. “Big, tough guys.” She picked up her coffee and brought it up to her lips. “’Maybe they’re eight feet high with four heads,’ Henk says, and you says you think they’re going to look more like spiders. And Henk says he wonders how to tell the women from the men. Don’t you remember that, Jake? She took a sip of coffee. “Such big talkers with their girlfriends. But you guys were scared too—”

“We knew it was a big nothing, just knew it.” Jake rubbed his hand over his beard. Betts had told him he should shave before breakfast as long as Shelley was visiting.

“Big tough-guy heroes. You know what boys are like, Shelley,” Betts said. “They don’t change a bit—”

“There we are, searching the skies," Jake said. "A hundred thousand stars out there, perfectly calm and clear, and we’re watching for the end of the world--”

Betts interrupted. “And always yacking too. ‘They’ll get O’Connor’s place first 'cause they want that new Farmall of his,” you said. And Henk laughs and laughs. But we knew you were scared. We could tell.” She pointed right at him with her cup.

“Were not,” he said.

“Were too—you were scared silly.”

“Ah, Ma, you think you remember it all so clear but you—”

“If you weren’t scared, you'd have wanted to neck. That’s all we ever did out there otherwise,” she told him.

"Ma!" Jake said, edging his eyes at Shelley.

“You were scared, and you know it."

“Sounds like guys I know,” Shelley said.

“Tell her the rest too—go on!” Betts said.

“We sit out there for some time, and then Henk, he says that maybe we ought to head back to town because maybe there’s some green men on the bank corner—”

“You were scared. Tell her why you went back,” Betts said.

“I don’t know why—maybe just to be around people is all—”

“You said maybe some men would band together and fight. That’s what you said..”

“We were just joking.” He waved his hand as if it were nothing.

Betts leaned over. “They were wanting to get their BB guns and join the Ireton National Guard.”

“Ma!” he said.

“We all went back to town finally,” Betts said, “and there were kids hanging around, and nobody knew anything more than what the preacher had said—that somewhere out east somewhere the Martians were coming.”

“By then it was almost nine—" Jake said.

“Just let me tell it,” she told him. “You’re always adding stuff.” Jake sat back in his chair. “So we’re all standing around downtown, and some kids are whooping it up and some are crying and some are just kind of sitting there as if they don't know up from down."

“So what happened?" Shelley said.

"Nobody seemed to know anything." She looked over at her husband. "Jake’s got it right about one thing. It was the Depression, and the preacher was pretty much the only one around with a radio—anyway the only radio playing on a Sunday night. So we figured, why not get the facts right from the horse’s mouth—”

“Good, Lord, Ma. That’s no way to put it.”

“You know what I mean, Shelley. So we went right up to the house and knocked on the door—there was Henk and Faye and you and me and about a dozen other kids from other churches too. We figure we should know for sure if it’s the end of the world. We knocked on the door, and preacher’s wife is the one who shows up.”

"She didn't look to me as if she spilled her marbles.' Jake said. Way too loud. And it wasn’t nice either, and Lord knows I’m not proud of laughing, but it was funny—“ Betts really couldn't help giggling a little. “Her eyes were all rimmed," she said, "and she had handfuls of handkerchiefs.”

“Looked a sight, she did,” Jake said.

“So Faye asks her, 'How is things with the end of the world?' she says. I remember that because how do you ask somebody about where on earth are the Martians last time they checked? And Mrs. Bergsma’s face melts into a smile. “It’s all nothing,” she said. “It’s all a hoax.”

“Henk didn’t know the word hoax, because he was real Dutch then yet, so I had to tell him,” Jake claimed.

“Preacher's wife says how sorry she is that she got everybody all scared out, but how if we’d have heard what they did on that radio, we’d have been scared too. ‘Now all of you just ought to go home,’ she says.”

“We knew it was stupid all along," Jake said.

“My word, all of that is true?” Shelley asked. “We heard it in school, but it seemed so dumb.”

“It was the end of the world in Ireton,” Jake said.

“Look at the time, girl," Betts told her. "You’re going to be late to school.”

“So did you guys go back to that place out in the country and neck a little, Grandpa?” she said as she picked up her bag and threw it over her shoulder.

“You just get on to school before you get yourself in trouble,” he told her.

Once Shelley was out to her car, Jake told Betts that what they’d just had was a pretty good breakfast.

“It’s just that you did all the talking,” she said. “that’s why you’re saying that.”

“Hadn’t thought about those Martians for years,” he said. “When I remember it now, I remember feeling scared, too, though—I admit it.”

“Don’t know what I’m going to do with you,” she told him, reaching for his cup.

“Oh, shussh, and pour me a half cup more, why don’t you?”

Wednesday, January 23, 2019

The End of the World in Ireton--ii

“We’re right in the middle of this talk about something-or-other in the catechism—something about doctrine, I'm sure, something like predestination," he said.

Shelley looked up as she'd just spotted a bug. Betts knew Jake was overdoing it.

"And all of a sudden in comes one of the preacher’s kids, boy named Corny," Jake said, both hands creating no bigger than a milk can, "just a little kid, sort of slinks in from the back, and Dominie Bergsma—”

It was clear Shelley had no clue.

“The preacher,” Betts grabbed Shelley’s arm as if to hold on to her. "He's talking about the preacher. The little boy was the preacher's son."

“—and Dominie Bergsma spots him back there, his own little boy, see? And so he stops talking—remember that, Betts?—for once, he stops talking. Oh, my lands, that guy could go on and on—remember that?" He looked at Betts as if she was just as thrilled as he was. "Bergsma stops cold on whatever it was he was talking about and cranes his neck as if to make out who’s just stepped in in the back of the room ‘So, Cornie,' he says, 'what’ll it be?” he says. Bergsma was kind of a joker too, though—you remember that, Betts?”

“Tell her the story, Dad,” Betts said, "just tell her the story."

“So anyway, Cornie’s just a shrimp, see? —and he’s scared of walking up in front of all the big kids, so he sort of wanders up, looking as if he could wish himself invisible." Betts was glad he was on the other side of the table from the chandelier because it'd otherwise be threatened. "By then all of us knew it had to be something big," Jake said. "Preacher’s kids don’t usually come walking into Young People’s, so we’re all hushed up, hoping that maybe we can pick up some secret here when the kid tells his old man what’s going on." Jake lifted a finger up in front of his lips. “’Pssst, pssst, pssst,’ that’s all we hear. But the good Reverend turns green up there in front of us—”

“Don’t overdo it, Dad,” Betts said.

“I remember like it was yesterday. He’s leaning over to hear his boy whisper, then he stands up straight, and he looks like he’s going to faint. He takes his one huge swallow of air and straightens his shoulders." All the while Jake is acting out what he's saying, like some guy on TV. "The kid darts right out of the basement like his pants's on fire, and then Bergsma says, real straight-faced, you know, like a trial judge or something. I'll never forget that moment. it was so terrible odd. 'It seems the Martians have just landed somewhere out east—’

"Just like that he says. Now Bergsma had this straight-faced way of making jokes, you know? And everybody is used to it, so when he says about the Martians, we all just bust out laughing—the whole kit’n’kaboodle.

“'I’m not kidding,' he says, and we're all about falling off the chairs.”

Shelley couldn’t stop herself. “Wasn’t really like that, was it, Grandma? He’s just telling stories.”

“Your grandpa likes to turn up the drama,” Betts told her.

“When finally he gets us settled down, all the time saying how we’ve got to believe him. And then he says it again, see?—how the radio claims maybe it’s the end times now, the end of the world as we know it.”

“That’s just about how it happened," Betts admitted. "I was there too.”

“Finally, he gets us settled down, and all the time saying how we’ve got to believe him. And then he says it again—how the radio claimed it was the end of the world.”

“From Martians?” Shelley said.

“That's what the preacher said all right,” Betts told her. “Your grandpa’s got that right.”

“Thing is, we're thinking how the preacher’s wife listens in to radio shows on the Sabbath,” Jake told her. "You know, people thought that mighty wrong, even a sin."

“Lots of things were warned against,” Betts said. "Trust me, lots of things."

Meanwhile, Jake was acting like Reverend Bergsma. “Right now I am dismissing Young People’s because the world is going to end, and I want to be with my wife—’ he says. And Jack Tolsma, he says kind of soft that maybe the two of them are going to go in totally different directions—well, you know—now that it’s the end of things. Then Jack sticks his head down between his knees 'cause he can't stop laughing—“”

He didn’t need to say that, Betts thought.Their granddaughter didn't have to hear that.

“Then he just up and walks out, saying how everybody ought to go home. Well, you can’t believe everything you hear anyway, we're thinking. Besides, it was the Depression times, and we couldn't help wondering what on earth Martians would want in Ireton anyway? That's what we were thinking."

“'I’m not kidding,' he says, and we're all about falling off the chairs.”

Shelley couldn’t stop herself. “Wasn’t really like that, was it, Grandma? He’s just telling stories.”

“Your grandpa likes to turn up the drama,” Betts told her.

“When finally he gets us settled down, all the time saying how we’ve got to believe him. And then he says it again, see?—how the radio claims maybe it’s the end times now, the end of the world as we know it.”

“That’s just about how it happened," Betts admitted. "I was there too.”

“Finally, he gets us settled down, and all the time saying how we’ve got to believe him. And then he says it again—how the radio claimed it was the end of the world.”

“From Martians?” Shelley said.

“That's what the preacher said all right,” Betts told her. “Your grandpa’s got that right.”

“Thing is, we're thinking how the preacher’s wife listens in to radio shows on the Sabbath,” Jake told her. "You know, people thought that mighty wrong, even a sin."

“Lots of things were warned against,” Betts said. "Trust me, lots of things."

Meanwhile, Jake was acting like Reverend Bergsma. “Right now I am dismissing Young People’s because the world is going to end, and I want to be with my wife—’ he says. And Jack Tolsma, he says kind of soft that maybe the two of them are going to go in totally different directions—well, you know—now that it’s the end of things. Then Jack sticks his head down between his knees 'cause he can't stop laughing—“”

He didn’t need to say that, Betts thought.Their granddaughter didn't have to hear that.

“Then he just up and walks out, saying how everybody ought to go home. Well, you can’t believe everything you hear anyway, we're thinking. Besides, it was the Depression times, and we couldn't help wondering what on earth Martians would want in Ireton anyway? That's what we were thinking."

"So you stayed in church?" Shelley said.

"None of us really felt much like going home. After all, Young People’s was the only time we got out all week, since it was the big night—Sunday night. We didn’t have no radios. We just thought Mrs. Bergsma lost a screw.”

“Jake!” Betts said.

“Well, it’s true. You know it too. There was some of us that had trucks and cars, but mostly it was wagons back then, it being the Great Depression. So most of us just hung around downtown because nobody really believed little green men from Mars was about to land on the prairie—”

“What a riot,” Shelley said. “You guys had all the fun. So then what happened?”

_______________________

Tomorrow: more memories roll.

Tuesday, January 22, 2019

The End of the World in Ireton

The story I'm going to tell is thirty-some years old. The story behind this story, a media phenom people still talk about, is much older--the night Orson Welles conned a nation into believing the Martians had landed, October 30, 1938. Prof. Lou Van Dyke, who died just last week, told me what he remembered about that night, a Sunday night, in a tiny Iowa town, where his dad, incidentally, was a preacher. I loved it.

No, this is not exactly what Lou told me. It's been retooled as fiction; but there's a prototype, the story Lou once told. I'm telling it once again, thirty-some years after it appeared in The Banner, in his honor.

Betts did her best to serve up big breakfasts the week their granddaughter stayed over, even though Shelley picked over her eggs like a blue jay and usually left enough ham to feed a starving family. At least that’s how her grandfather saw it, once Shelley was off to school. “Kids are all spoiled nowadays,” he’d say. “It’s a sin.”

At breakfast on Wednesday, as usual, the two of them couldn’t get much of a word out of their oldest granddaughter. She kept staring down at a tablet scribbled with school notes, and Betts knew very well what Jake was thinking right then—how in the olden days breakfasts used to be big, noisy times around the family table, eight kids, ma and pa, a hired man or two, depending on the season, lots of chatter.

He squinted at Betts, as if what his granddaughter was doing was downright impolite. But Betts let it pass, because she knew very well that Jake painted rosy pictures of what used to be. “It’s a sign of old age,” she had warned him often enough.

“Rosebud,” Shelley said, speaking softly, to herself. “Rosebud, rosebud, rosebud.” That’s all. Just “rosebud.” Fifty times maybe, Betts thought. The only word she used.

“What that mean anyway, sweetheart?” Jake growled.

“I hate tests,” the girl said.

Betts knew exactly what her husband was thinking: “Every last one of them kids is spoiled. Got no sense of what ought to be. Can’t even keep up a conversation.” She hoped he wouldn’t come out with all of that. He was capable of it, that’s sure.

“We got a test on this dumb old movie.” She whirled up her eyebrows and faked a yawn. “Boooooring,” she said. “It’s about this guy who gets real famous and then loses it all, and at the end all he says is ‘Rosebud, rosebud, rosebud—‘”

Jake dipped a forkful of ham in the liquid yoke of his eggs. “Hear that, Mom?—today they study movies at Christian High. I remember you got called by the consistory if somebody claimed they saw you even close to a theater.”

“You should know,” Betts said. That shut him up.

“You ever hear of Citizen Kane?” Shelley said. “Boorrring. This big fat famous guy made it—Orson Welles.”

Jake laid his fork down. “I should know that name—”

“He made the radio show about the Martians and the end of the world.” Betts told him. “You remember that.”

“That’s the guy,” Shelley said. “'War of the Worlds' --you guys actually heard of it?” She looked at them as if she had just then discovered they were alive.

“The invasion of the Martians.” Jake leaned back in his chair, crossing his arms over his chest. “It was the end of the world in Ireton,” he said. “What a night.” He shook his head. “Can't ever forget that one.” The silly grin he gave Betts was one she knew too well.

“We read about it,” Shelley said. “I mean, it was really dumb what happened—people jumping out of windows and freaking out—”

“Happened on a Sunday night,” Jake said. "On the Sabbath."

“You actually remember it?” Shelley asked. "Seriously?"

“Me and your grandma lived through the whole crazy business,” he said. “It was a Sunday night I remember, and we were over at the church for Young People’s Society—”

“Church on a Sunday night?” Shelley said.

“Things were different then, honey,” he told her. “We didn’t have a thousand and one things to do, so it was a big night for us, a big night out.”

Shelley looked like she’d just bit a lemon.

______________________

Tomorrow: the memories begin to roll.

Monday, January 21, 2019

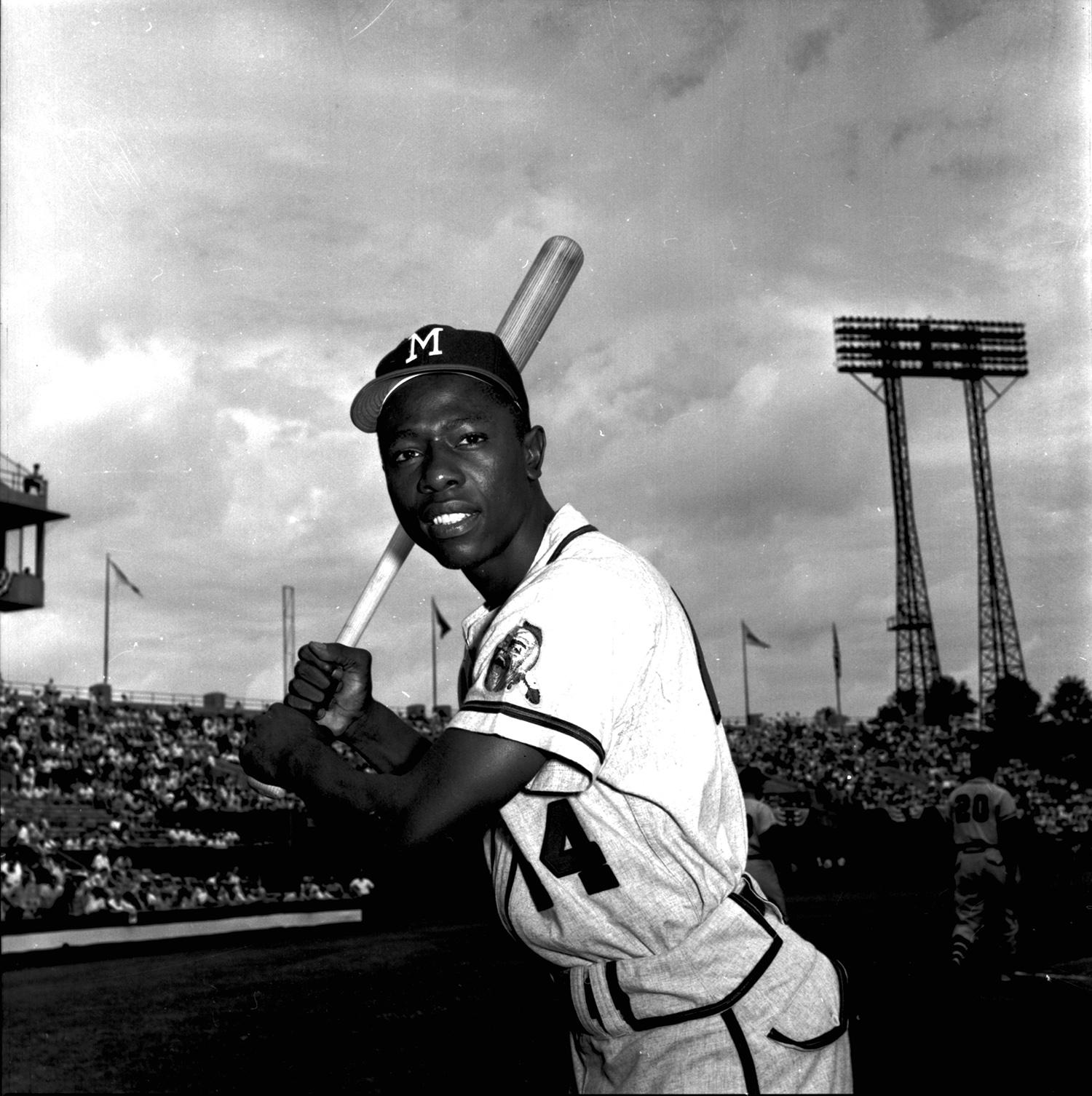

Hammerin' Hank and MLK

Seems to me that Billy Bruton played next to him in centerfield, so he wasn't the only African-American on the roster. But he was early. Those old pics of that 1957 team--World Champ Milwaukee Braves!--have four or five others.

All I know was that when I was a kid, on many a night I fell asleep with the Braves game still playing on that little radio up above my bed, it's soft yellow light over the dial. I loved going to sleep with the Braves, loved it so much that there were nights when I didn't even nod off.

Coming into the ninth, the Braves may have trailed, but if the heart of the lineup was on its way to the plate, there was always a chance. Hank Aaron was there, batting in the third position, followed by Eddie Matthews, the third basemen, at cleanup. Those two guys could hit. And did. That's what I remember thinking about Hammerin' Henry Aaron--the guy could hit.

Really, he was a little guy. Muscle-y? --sure. But Aaron had great wrists, my dad used to say, great wrists that snapped that bat with so much torque the stadium walls came tumbling down.

The biggest story of his professional life was how he finally outdid the Babe and ended his career with 755 round-trippers. That was two decades later, in 1976, the year of the American Bicentennial, the year our daughter came into the world. By that time I was well aware of his being African-American, as was the nation, because hate mail and death threats arrived daily as he climbed ever closer to the Babe's otherwise untouchable record. All that hate on the U.S. of A’s 200th birthday was obscene.

"You are not going to break this record established by the great Babe Ruth if I can help it," some guy told him in a letter. "Whites are far more superior than..." well, you put the word in. "My gun is watching your every black move."

Today, generations of kids can't imagine someone capable of such wicked hate, but it was in the air in 1976. The man who wrote those lines wasn't alone. Henry Aaron, an African-American, was threatening a great man's home-run record. A great man who was White.

Long before email or messaging, the Postal Service that year brought him nearly a million letters. Thousand and thousands in that massive bagfull were greatly supportive and loving. But America's finest racists couldn't go down without threatening a noose from the old days.

But they couldn't stop him. Hammerin' Hank still owns a shoebox full of major league records: most career runs batted in at 2,297, total bases at 6,856, and extra base hits at 1477. And there's more. There's lots more.

But I thought of him not long ago--I couldn't help it, really--when I saw his name on a stone carved into the sidewalk beneath me.

His footprints sit at the International Civil Rights Walk of Fame at the Martin Luther King National Monument in Atlanta. And he's in good company too--Thurgood Marshall, Ralph Abernathy, Edward Brooke, Rosa Parks, Jimmy Carter, and more than a dozen others. Something tells me, Hammerin' Hank is likely as proud of being there as he is in Cooperstown.

Breaking that record wasn't easy, not at his age. He played in 3300 ball games, third place all-time; but it wasn't easy to live as he did, in the eye of a racial storm that will likely never fully pass off the coast and out to sea.

On that day in Atlanta when he hit number 715, one more than the Babe, that day when some people were scared of what could happen, the image I like best is that when Henry Aaron came around third, there at the plate stood his parents. Isn't that just the greatest?

It was nice seeing him again there at the King Monument. I'm thankful for that sidewalk, for those footprints of his, and the tracks he left in my life. And yours.

Next time you’re in Atlanta, walk in ‘em. Try.

Sunday, January 20, 2019

Sunday Morning Meds--Joy

Delight yourself in the LORD

and he will give you the desires of your heart.” Psalm 37:4

Once upon a time, I was blessed to write the story of a Laotian-American, a man named Kong, a man who is a grandfather, a meat-packer, a prison camp survivor, and a self-described “mean dude” when he worked as for the military police in Laos before the communist takeover in 1975. I interviewed him some years ago.

The most important description I could give him back then, he told me, was that he was a follower of the Lord. He was raised by a strict but loving father, a strong Buddhist. Throughout his life, even in the decades he'd lived in North America—New York and then Iowa—he considered himself Buddhist. But no more.

Something happened—a miracle. One night, his nephew was on the brink of death, suffering horribly from an asthmatic attack. An ambulance was called, and the boy was rushed off to the hospital, where doctors did everything they could. Kong fell into the kind of despair that prompts all of us to pull out every last stop. He’d never been a believer in the Christian faith, even though his wife had occasionally read some things about Christianity.

What Kong knew was that he had an old friend—they used to be members of a party band together—who had found a new faith that had changed him, kept him out of the old wild wing-dings once he’d started to believe. This old friend had become a pastor. From the hospital, Kong tried to call his old friend and told him in no uncertain terms that if prayers to his God could do anything to heal his nephew—who was close to death—then he’d for certain believe in that God too. He’d even come to church.

On his cell phone, Kong found his old friend at a church meeting where a circle of Laotian-American Christians were, at that moment, studying the Bible. When the pastor put down the phone, the group held hands and prayed hard for the boy.

The nephew recovered, and the next week, Kong was in sitting in a pew right in front of his old musician friend, the pastor. Not long after, he and his wife were baptized.

I admire Kong’s enthusiasm. I admire his joy at finding a God capable of performing miracles like the one that he saw with his own eyes. Today, he and his old friend are making music together again, but now, he says, it’s in Christian worship and in praise to the Lord.

It’s a great story, and it’s absolutely full of delight, the delight of this verse from Psalm 37. The promise of this verse isn’t quite the equation of the story. Even before Kong delighted in the Lord, the Lord gave him the desires of his heart—and those of his family. Amazing.

The mysteries of the Lord God almighty, King of creation, include this incredible truth: he’s probably never used a Xerox. Ever. For all of his own children—and there are millions and millions—he’s used totally individual means to gather them to his love. Kong’s delight has grown from a single, miraculous answer to a single, fervent prayer. For Kong, “conversion” was dramatic, immediate, and radical. Some of us, on the other hand, he nurtures slowly. Some come reasonably; others come emotionally. Some come via the miracle of life; some arrive in his arms by way of death’s dark valleys. Some are dragged, kicking and screaming before his throne.

The promise of this verse is for all of us, however. Joy in Him means joy for us. That’s just as much a miracle, really. In that sense, we’re all copies of his love.

Friday, January 18, 2019

Prof. Lou Van Dyke --1928-2019

Who am I to doubt the wisdom of real educationists? I dare not question the research, but I can't help remembering the old days, when small groups were unheard of and profs stood up front to impart an hour's worth of wisdom, occasionally taking a question, but otherwise holding forth like Old Testament prophets.

Some were really lousy, but some were good. Some knew how to season a spiel with comic touches or so much passion we'd leave the room wondering how on earth we'd ever lived without knowing about the French Revolution or Sherwood Anderson or the Doppler Effect. Some delivered the goods by telling great stories.

Lou was one of those. I'm sure I'd still be calling him "Professor Van Dyke" if he'd not been a colleague not all that long after I was a student in his class--American history. Little did I know that I'd be spending most of my retirement in the history of the American West, a field he opened up for me in 1968.

For reasons I don't remember all that well, that particular semester wasn't a good one. Part of it, I'm sure, was the late 60s world, Vietnam, and the tight conservative politics at a small, Christian college campus in a far corner of Iowa. I was starting to discover ideas that put me outside the circle of righteousness, which could be, back then, very tight. I'd applied, in fact, to the university back home in Wisconsin, thought that seriously about leaving Dordt College.

And I skipped class. Too often, in fact. It was a bad semester all the way around. My grades tanked.

Sometime that year, I missed a quiz in Professor Van Dyke's American history. Classes were big at Dordt College back then--fifty, sixty, seventy kids in American History, requirement for graduation. I didn't show up one day when Lou gave a quiz.

No big deal. I had roommates who took it. They got me the answers.

I went in to Professor Van Dyke when he made it clear no-shows had better take the quiz. Aced it. I was brilliant.

Professor Van Dyke called me in, sat me down in his tiny office, pulled out my quiz, showed me what I'd done, then suggested he had some reason to doubt me because not one other kid in the entire class managed to get every last answer right. I don't remember the conversation, but I do remember him giggling. He had me dead-to-rights.

Cheating, back then, must have come easier to me than lying about it. I admitted the whole truth, so help me God. But Professor Van Dyke didn't reign down holy terror, didn't fail me, didn't threaten to send a letter home (those things happened). I didn't ace the thing, but I don't know that he counted what I'd done against me or not. I don't remember. All I do remember is Professor Van Dyke being vastly more agreeable than I would have guessed a Dordt College prof would have been, circa 1968. I remember a giggle.

A decade later, he'd become my colleague, but I'd not forgotten what had happened ten years before. Hard as it may be to believe, most faculty back then would stop whatever they were doing about three in the afternoon and head over to the coffee shop. I remember exactly where we were that day--Lou and I--on the sidewalk over to the SUB, when I brought up that perfect quiz. I had to sometime, I knew.

"Lou," I said, "it's been bugging me--you remember that time I cheated on that American History quiz?"

He kept walking. "What?" he said, and that was before he had a hearing aid.

"When I was a student--when I cheated on that test, got the answers from my roommates, you remember?--"

Then he stopped. "In my class?" he said. "You're kidding."

"It sticks in my mind," I told him. "Just wanted to bring it up." Maybe I said something about guilt.

Lou always had a wry smile, loved irony, was always just a bit wayward himself. That day, I don't think we missed a step on our way to the coffee shop. He just looked at me with that sly grin and giggled. Just giggled.

He was a wonderful guy, a colleague for a couple of decades at least with an ample supply of great stories. Throughout his entire career at Dordt, he was one of very, very few sworn, out-of-the-closet Democrats, and he was always proud of it.

That story sticks with me. When I think about it, I can't help but believe that Lou Van Dyke, every once in a while, probably felt himself somewhere just outside the circle of righteousness too.

I don't know, but I can't help thinking that there may well have been a time that Professor Van Dyke, Lou, the preacher's kid, may well have cheated on a quiz himself.

Thursday, January 17, 2019

The once, but not future, King

There could be no clearer indication of the immense power of Sioux County Republicans than the fact that Governor Kim Reynolds came to Sioux County, to Sioux Center, on the day before the election. Most of the state of Iowa, the populace of the east central area—Des Moines, Waterloo, Cedar Rapids, Iowa City, etc.— could normally care less what happens out in the faraway wild west.

Gov. Reynolds, in her first open race for the office, chose to end her campaign events here because nowhere else is the populace so defiantly Republican. Sioux County is her base--shore it up, get ‘em to the polls, fill ‘em with spit and vinegar, and they’ll take you on home to victory—that’s what her people must have determined.

The old jokes are just that: “Sioux County Democrats are meeting next week in the Main Street telephone booth—public invited.” Even though the Democratic party is showing some muscle as of late, Sioux County has always been blood red. Why?—that’s a good question, but most anyone who thinks about the region starts that answer with just one word—“abortion.” “Republicans are agin’ it. Democrats are baby killers.” You know. That one.

Abortion is first, but another reason for the huge Republican crowd is that the GOP is old-time religion—pure, unsullied tradition. What’s good for Granddad is good enough for me.

For those of us who take a path a bit farther left, it can be disconcerting to feel surrounded by so many right-wingers; but most of us, especially if we’ve lived here for some time, understand the first answer. If wanting Roe v Wade shipwrecked is an absolute, Sioux County Democrats will continue to be a minority, even though they’re outgrowing telephone booths.

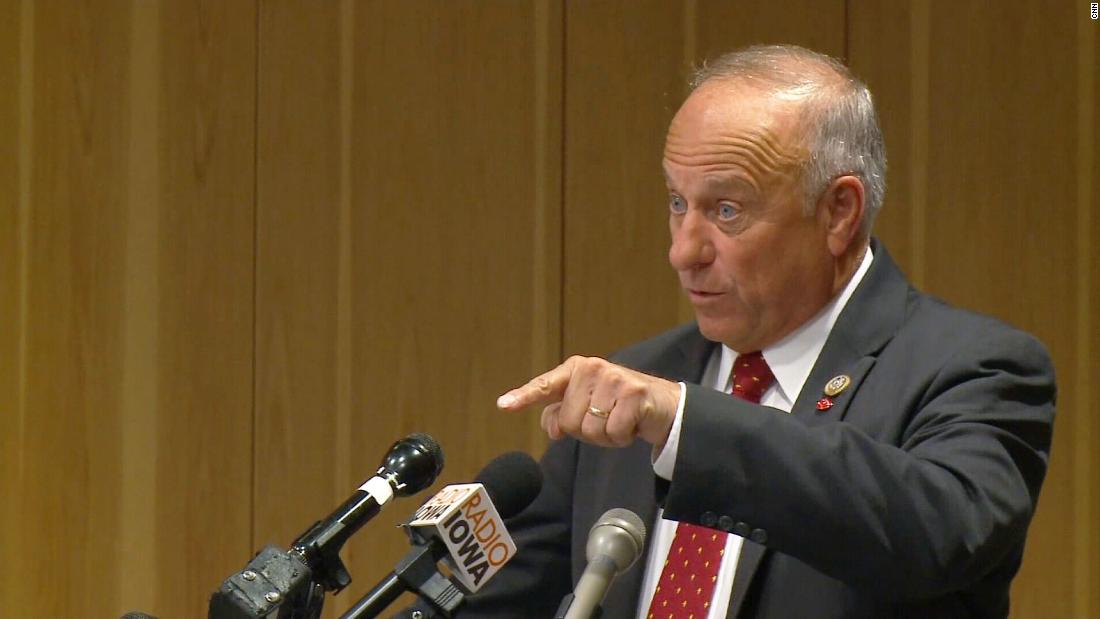

Maybe—just maybe—all of that helps some of us understand what on earth happened in the last election, when Steve King smacked down J.D. Schouten here in the county, the same Rep. King whose ideas are considered suspect (at best) by everyone from Gov. Reynolds to Liz Cheney, Kevin McCarthy and Steve Scalise, numbers one and two and three in the Republican Congress. This same Steve King brutalized Sioux County like some huge Alton freight—73.4% voted for a man widely considered--and now officially called--a bigot. Lyon county came in second at 72 percent. Throughout the district, shockingly J.D. just about won.

That hefty support horrifies farther-left types like me. That so many of our friends and families and neighbors support someone just about everyone, including Republican leadership, considered not only out of touch but out-and-out racist—well, that seemed impossible the day before the election. But it wasn’t. Steve King won here. He won big. Really big. Huge. He swept Sioux County as if the county were his sweetheart.

So, lots of people from all sides of the political spectrum are anxious to see what difference Rep. Randy Feenstra makes in the next primary go-round, if King is around. Feenstra got himself in this week. His conservative credentials are impeccable, despite the cheap shots King is already taking at him. Feenstra is just as adamantly pro-life, wants to support the Trump agenda, hits all the right Republican keys—or so it seems to me. Not only that, he’s local, grew up here, educated here, is employed here, goes to church here.

I’d like to think that in the next Republican primary. Rep. Randy Feenstra will entirely clean Steve King’s clock, wail on him, smash him like a corn borer. I’d like to think that next time around, Feenstra will take 75 percent of the vote in Sioux County, at a minimum.

That’s what I’d like to think.

I’ve been wrong before. Oh, my word, have I been wrong.

Wednesday, January 16, 2019

Me and bad news ads

I'll admit that when it comes to this incredible machine in front of me, I mostly stumble along like some stooge, knowing only what I have to keep my nose to the digital grindstone. This Dell will do a gadzillion tasks I don't know a thing about, but if someone were to show me the brave new world I'm missing, I'd forget the route inside of a day and a half anyway.

There's this, for instance. Lately, these ads appear with annoying regularity. Mostly they try to grab my attention in the hallowed old way of the National Enquirer, spouting juicy stuff. at the grocery counter. This particular one simply assumes I'm all agog at royalty. I'm not. Princess Meghan is fetching--I get that; and I think there's some chatter about whether or not she and her sister-in-law hit it off, but I don't need her foibles in my life so I stay away (Oh, yeah, her dad's a jerk too, right?).

But until I swipe it away, a couple times a day ornery pop-up headlines appear in the lower right-hand corner of my screen. I didn't ask for it, but then I don't doubt some errant keystroke of mine may have given it birth. "theweathercenter.org" it says for some reason I don't know. And Google Chrome. Maybe once an hour some celebrity--just now Steve Harvey (who's Steve Harvey?) will show up beneath the same title: "Sad news for. . ." I guess "enquiring minds want to know."

I don't.

But the approach is arresting. It's always "sad news for," or some browbeaten equivalent. Here's one:

Never cared much for the Clintons, and I'm certainly not going to start right now.

Whoever dreams these things up and wedges them into my daily grind wants me to push that little green button. Well, I won't. But that doesn't stop the ads from jumping up out of nowhere to bless me with their gift of sad news.

What I can't help wondering is what ad guru determined that me and a million others would click on "sad news," as if we were hungry for someone/anyone to say something really dismal about some starlet's rocky marriage? Who thinks of these come-ons anyway, and who do they think we are?

Here's my theory. Some Silicon Valley wonderboy's logarithm long ago determined my age. Whoever did, creates these things with this premise: I'm an old fart, prone to exasperation with a world I no longer understand. He thinks I'm as useless as a cream separator and therefore get pouty, prone to indigestion and the kind of windy exhortations one hears only in the minor prophets. I'm 70 years old and a pessimist--we all are. I get these blasted ads because I'm old. If I were 19 or 29 or even 49, I'd be on a whole different listing. Maybe I'd get bosomy females, but I wouldn't get a chorus of sad news takes.

How about this?

Only old farts think much about flushing their bowls. Someone with loads of money honestly believes I'm charmed by this stuff. Someone thinks I'll click on the darkness because at three-score-and-ten, real light has gone out of my life. Someone believes I love sad news.

Well, I don't, dang it. Bring on the bosoms.

Tuesday, January 15, 2019

On the birthday of MLK*

To say he came out of poverty would be a stretch. His family wasn't poor, the neighborhood had standing and the house had character. His parents were by no means rich, but neither were they ever destitute. For a black man in the American South, growing up in the Depression, he and his family had a certain amount of privilege.

As a kid, he played across the street at the local fire station, where the squad--all white--was entertained by neighborhood kids.

They went to church up the block at a place made famous when, as a preacher, he came back to lead the congregation.

It's called the Martin Luther King National Historic Park because the whole neighborhood seems holy now. Inside Ebenezer Baptist, no one talks much--mostly whispers because his sermons changed everything really.

That assessment may be exaggeration. After all, this isn't Charlottesville, but it could be.

And the truth is, certain aspects of the old way are gone now, never to return.

But all of that took some doing, and lots of it wasn't pretty. Millions of white Christians considered him a communist. He was trying to upend the system. One of those assessments was true. The other was created from fear and hate.

He spent some considerable time here, thought the cause worth the suffering.

He wasn't alone.

Eventually, with his inspiration and leadership, thousands marched.

He took his inspiration from world leaders who preached non-violence.

This is his copy;' those notations belong to him.

_____________________________

* First published a year ago. One additional story: yesterday, Iowa Fourth District Congressman, Steve King, who has, for years, said things most people thought racist, was yesterday stripped of his committee assignments by his own Republican party. Racism isn't gone, but many of us can celebrate that his own colleagues eventually had enough of his race-baiting.

Monday, January 14, 2019

Green Book: a review

Just in case you haven't seen it, let me say that Green Book is a marvelously entertaining movie. It's won all kinds of accolades and is an almost certain Oscar nomination.

The story is in that ad picture above. It's the Fifties, and there's this New Yawk Italian stallion, a street tough, an enforcer, who's out of a job. As unlikely as it sounds, he gets himself hired by this super-educated African-American musician who wants to tour the Jim Crow South. A highly accomplished concert pianist, the man is an artist who deliberately puts himself in a region where rich white people delight in his Rachmaninoff but detest his race.

There will be trouble, and there is.

The story is episodic, one concert appearance lined up after another; all firmly set in America's racial history. Even though today we like to think Jim Crow is gone, racism isn't--witness our own Fourth District King. But Green Book is not just about history or racism or politics or hate. It's about two human beings who begin the pilgrimage one way, and end it another. The events of the world they experience change both of them, and there lies the trouble.

This marvelously entertaining movie has taken some shots it probably earns. Some feel it's just another story of how white people save black people, a cliche, a stereotype in and of itself. Some think it melodramatic, overdone, sappy--its travel stops deliberately underplayed to keep white audiences happy. Some claim it's just plain too cute, another Disney movie.

I loved it. Then I read the negative stuff and felt guilty that I did.

The two men at the heart of things are instantly recognizable characters. Tony Lip (Viggo Mortenson) is a Mafia thug from a thoroughgoing racist part of town. Dr. Don Shirley is something of a diva, a Black man sworn to break through racial barriers but, by his own life experience, somewhat estranged from ordinary black folks--or their world. When the story begins, both are tenderfoots who, in the trip they take, have to come to grips with the limitations they carry but don't or can't acknowledge or even understand.

Green Book features two dynamic characters, two human beings who have to suffer before they grow. They do--both of them. Just one of the strengths of the movie is that their individual growth happens simultaneously. Their journey through Dixie hatred pays real benefits to both the white chauffeur and the black virtuoso. They both learn--and from each other.

And that makes Green Book into a human drama, not just a racial drama. And that characterization, to some, makes the movie feel like a Mardi Gras mask, a delightful smile to cover the grim darkness of American bigotry, its systemic racism. Because it makes us laugh when we should be crying, some consider Green Book to be fairy tale falsehood.

I'm white. I don't have a doubt in the world that if I were black I would see things differently, but I thought it was a terrific movie, a joy--and there lies the nature of the attack on the film: the racial problems this country faces are not a joy.

Green Book showcases well-earned racial reconciliation. Ironically, and sadly, it has also come to illustrate the very problems it wants to address, specifically how difficult racial reconciliation actually is.

It's a beautiful piece of work that'll have you laughing and crying, doing what movies are meant to do. If you don't know Jim Crow, you can't leave the theater without witnessing a history lesson on what it was.

But if you think all of that is behind us, you're dead wrong. Witness the controversy. Green Book may well be nominated for an Oscar, but don't look for it to win.

We've not put the problems it addresses and creates behind us. That'll be some time.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)