It may well look like a typo, but it most certainly isn't. What's more, there's nothing particularly funny about the word funerary. The truth is, it's a word that's barely pronounceable. Funerary--something about it sounds like a speech impediment.

Just recently the Nebraska Historical Society presented the Ponca Tribe with a collection of funerary objects, things once buried beside the mortal remains of men, women, and children, loved dearly, who once upon a time lived here in Siouxland. Decades ago, those funerary objects and the human remains were unearthed during construction projects and ended up with the Historical Society, whose task it was to identify them.

The Ponca tribe will now take those ancient objects and those remains, wrap them in blankets, and rebury them--along with new funerary objects like tobacco, sage, and other symbols and gestures of prayer--in a remote cemetery on tribal land, where, by the way, they will neighbor similarly repatriated remains reburied there in 1003. The inscription on that grave reads like this:

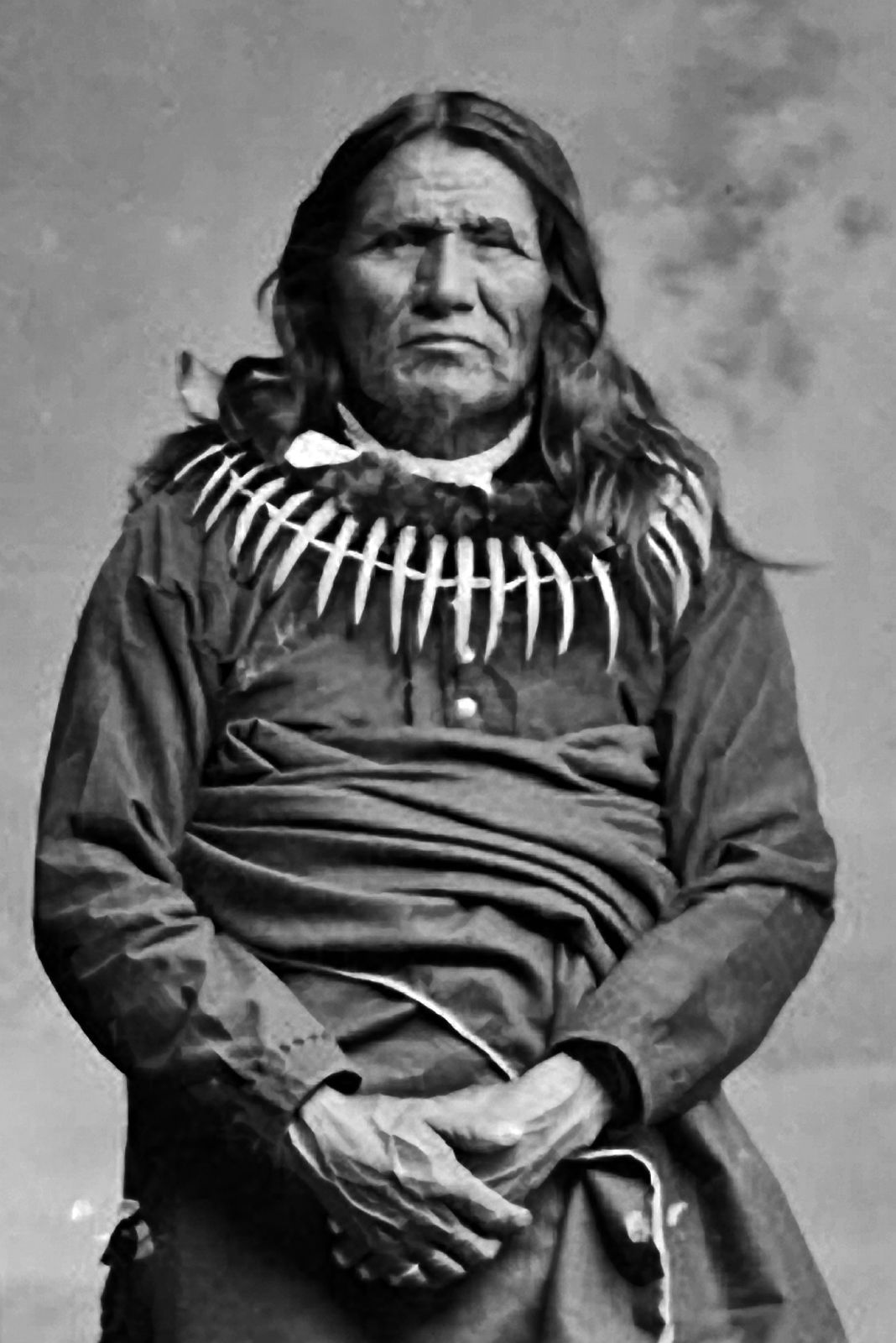

Here lie the remains of 584 Individuals of American Indian descent & 70 associated Funerary objects claimed jointly by the Pawnee Nation of Oklahoma and the Ponca Tribe of Oklahoma. God bless their souls and may they rest in peace.And all of this funerary activity among the Poncas is a reminder of one of the most important stories of our whole region, the story of Standing Bear, a story that cannot be told often enough. The burden Standing Bear carried was also funerary objects and the mortal remains of his son, Bear Shield.

In the 19th century, when the region suddenly overflowed with white folks, land was at a premium. By popular sentiment among the immigrants, Native people were simply "in the way." The reservation system was created, and some parts of the region were ceded to its first nations. In that process, via the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868, the Poncas were simply overlooked, their land ceded to the huge Sioux nation, their traditional enemies. For the Poncas, that mistake made death far too intimate a neighbor.

In 1875, the Poncas signed a treaty which sent them to Indian Territory, Oklahoma. But they didn't understand they were bound for Oklahoma; they'd assumed they'd be sent down the Missouri to their friends and relatives, the Omaha. When Washington made clear they were, in fact, Oklahoma bound, ten Ponca chiefs traveled south with the government agents to look over the new land.

Eight hated the place. The agent got mad at what he read as insubordination, and those eight chiefs, including Standing Bear, simply walked home, 600 miles, back here to the place where their ancestors were buried, a place they'd rather not call "Siouxland."

Washington didn't care what the Ponca liked or didn't like. The solution to "the Indian problem" was to give all the Indians their own country, "Indian Territory." Poncas, who'd never gone to war with the invading whites, were Indians; hence, Oklahoma.

First 100, then 500 Ponca left on their own "Trail of Tears." The arduous trip down to the northeast corner of "Indian Territory," the extreme heat and cold, and the lack of any accommodations at all led to the death of one third of the Ponca people in that transition. One third.

Included among the dead was Standing Bear's daughter, Prairie Flower, who had died on the Trail of Tears, and his son Bear Shield, who died of malaria, at Christmas, 1878. Bear Shield, just 16 years old, begged his father to return his remains to the Ponca homeland, at the confluence of the Niobrara and the Missouri.

That was the burden Standing Bear was carrying, the human remains and funerary objects of his oldest son, who wanted to go home.

_________________________

Tomorrow: Standing Bear's homecoming, a civil rights story.

No comments:

Post a Comment