“Why do you pray?" he asked me, after a moment.

Why did I pray? A strange question. Why did I live? Why did I breathe? "I don't know why," I said, even more disturbed and ill at ease. "I don't know why."

After that day I saw him often. He explained to me with great insistence that every question possessed a power that did not lie in the answer. "Man raises himself toward God by the questions he asks Him," he was fond of repeating. "That is the true dialogue. Man questions God and God answers. But we don't understand His answers. We can't understand them. Because they come from the depths of the soul, and they stay there until death. You will find the true answers, Eliezer, only within yourself!"

"And why do you pray, Moshe?" I asked him.

"I pray to the God within me that He will give me the strength to ask Him the right questions.”

― Elie Wiesel, Night

I read Elie Wiesel's Night when I was far beyond the age of innocence. I don't know that the book would have had the effect it did had I been a kid. Night is Holocaust Literature 101, the gate into the genre. The Diary of Anne Frank may well be more human, more warm, more touching; but Ms. Frank didn't make it, as everyone knows. She died in Auschwitz and therefore didn't go on living after the fact; she didn't have to remember.

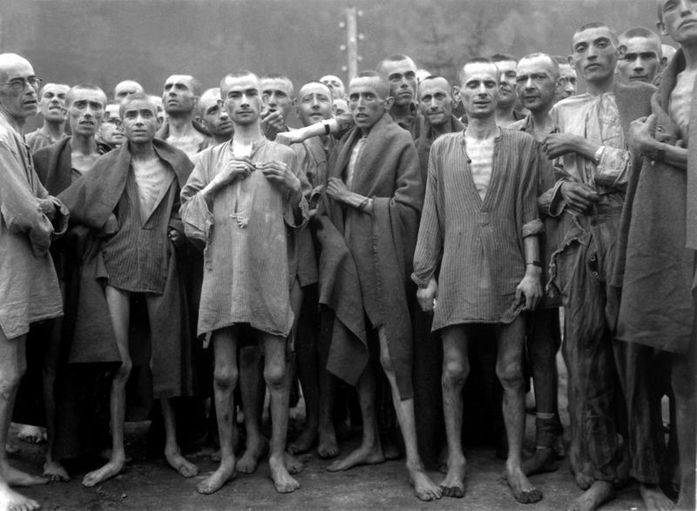

Wiesel did. He's one of those who was there when Allied troops walked into the camp at Buchenwald and put an end to terror and horror no one who wasn't there can imagine. When the SS beat his own father to death, Wiesel simply watched, not in horror but in fear that it would happen to him.

His silence at that moment seems the very heart of Night, the silence, the emptiness he felt at his father's beating, when his own concern was only for his own life. That isolation robbed him of his humanity, every bit, even his faith.

I don't know that I'd ever read a testimony quite like Night. Wiesel, I thought, owned a faith that is secure--I don't think belief in God during that long year he spent in the camps, nor in the years following.

But the God of his pious Jewish childhood was absent without leave in the camps. He left them, took up residence elsewhere, because he certainly wasn't there loving the men and women he left behind to evil. I had never read someone who didn't abandon belief as much as feel total abandonment from a being he'd once believed loved him, loved us. That God, Wiesel discovered, was not to be found at Buchenwald. He had departed.

The path of his life after the war was created on the day of liberation. No survivor saw as pointedly his or her own calling; no one, it seems, felt the duty or determination to remember and not to forget, to tell the world what happened before his eyes and within his mind and heart. He determined to tell that story, not as if to gain thereby some relief from nightmares, but because such horrors should never happen again.

The path of his life after the war was created on the day of liberation. No survivor saw as pointedly his or her own calling; no one, it seems, felt the duty or determination to remember and not to forget, to tell the world what happened before his eyes and within his mind and heart. He determined to tell that story, not as if to gain thereby some relief from nightmares, but because such horrors should never happen again.

I didn't read the book years ago but I remember a review of some work of Holocaust fiction in which a survivor, as dedicated as Wiesel to telling the story, begins to feel senility creeping in. No pain, nothing the man could suffer could be worse to him than forgetting, than not testifying.

Elie Wiesel dedicated himself to the impossible task of cajoling the world, reminding them, time and time again, not to forget.

He died last week, but Night, a very slim volume of Holocaust horror, will have a shelf life far longer than his own. His voice will continue to be heard.

Yesterday, a car bomb took the lives of 200 people in Baghdad.

The real question is who will listen?

No comments:

Post a Comment