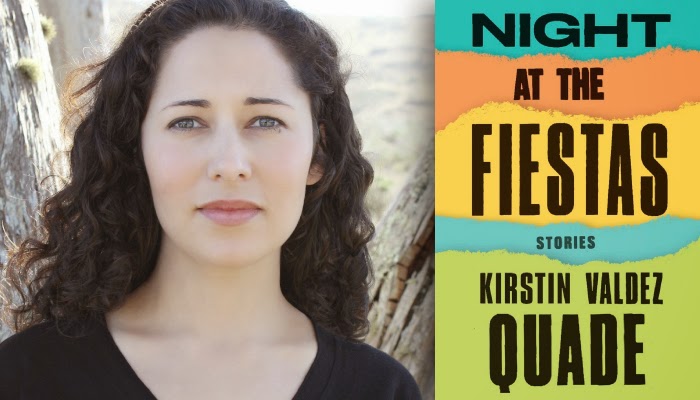

I stepped into the world of Kirstin Valdez Quade somewhere close to the beginning of Lent. Couldn't have been a better time really, although I had no clue about what I was getting into. Ms. Quade's stories in Night at the Fiestas, her first book, create a darkened museum of suffering, which sounds--I know--awful.

But maybe not today, not Good Friday, the setting for "The Five Wounds," a story which takes on a subject few writers would dare approach. "This year," the first sentence announces, "Amadio Padilla is Jesus." Because all of her stories in Night at the Fiestas are steeped in Mexican culture, that sentence directs a reader to some kind of passion play, a small town where Holy Week rituals are bold and scary and bloody.

Amadio is no fair-haired Jesus either, she tells us, "no silky-haired, rosy-cheeked, honey-eyed Jesus, no Jesus-of-the-children, Jesus-with-the-lambs." He's lazy, judged a good-for-nothing by those around him and for good reason. What's more, he hasn't seen Angel, his own daughter, fifteen and pregnant, for a year or more. What's more, he can't even remember the last time the two of them were alone. He's a long-shot at playing Christ, but his uncle, who runs the show, tells neighbors it might be good for Amadio because "he could use a lesson in sacrifice."

Angel isn't one. She's loud and vulgar and offensively childish. Oddly enough, her innocence is bested only by her brassy arrogance. But she's just a child, eight months pregnant.

Amadio has the lead in the kind of ritual observance Roman Catholic church hierarchy has long rejected, rituals you might expect to find in small towns where nothing ever changes. Men in black hoods bloody themselves as they stalk the Christ, who lugs the cross up a two-mile path to the town's own Golgatha. It's not pretty. As Amadio himself insists, it's something the children will never forget, but it's certainly no Rose Bowl parade.

The question that haunts Amadio is whether or not he will be strong enough to take the ritual nails through hands and feet, whether his selflessness will go that far. A former Jesus who suffered the nailing years ago still can't open his hands, but what Amadio believes is that his own worthiness will be dependent upon the extent of his willful suffering. If he can be Christ, the entire ritual will be memorable, and he will be transfigured before the village.

What Kirsten Valdez Quade does in "The Five Wounds" is reenact the crucifixion using a man so utterly unlike Christ that the fact that she's doing it is astonishing. Amadio Padilla is the amigo Donald Trump draws up to create white disciples, but through the ritual crucifixion Amadio is not lost because he believes--he surely does--that if he can do this thing, something good can happen, both to him and for his community.

I never saw Mel Gibson's The Passion of the Christ, perhaps because the whole thing felt like a come-on. I know lots of believers were blessed, and I believe that in my own faith tradition--a tradition that doesn't hang crucifixes--our radiant joy at the resurrection sometimes too fully eclipses Christ's suffering on this very Good Friday. But The Passion wasn't for me.

Then again, really, neither is this story. "The Five Wounds" takes you through suffering most of us choose not to imagine. Finally, Amadio suffers the nails. But he comes to understand that he is not "the Son," not Jesus Christ. "The sky agrees, because it doesn't darken," Quade writes. "Amadeo remembers Christ's cry--My God, why has thou forsaken me?--and he knows what is missing. It's Angel who has been forsaken."

There could be no resurrection, no Easter, without Good Friday. "This year, Amadeo Padilla is Jesus Christ," the story announces right up front. And, thank the Lord, because for the first time in his life, it made him see.

One could do worse on this Good Friday.

1 comment:

Dirk here. One of those stories got into The New Yorker, Jim.

Post a Comment