My first perceptions of nuclear war came when, as a grade-schooler, we snuck under our desks in preparation for destruction many thought imminent. It was the early 1950s, and my father, who’d spent the war years in the South Pacific, signed up to watch the sky with the local Civil Defense unit. He left a chart picturing different Russian aircraft on our breakfast bar, and I studied those shapes as if to be sure that, should I spot something up above on my way to school, I’d know evil from good.

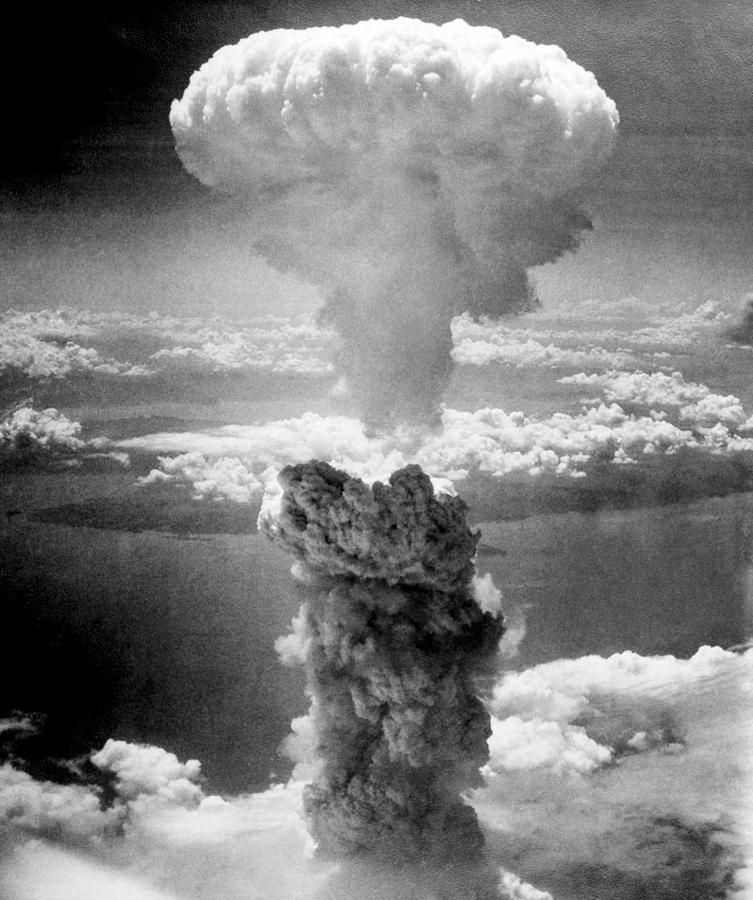

I must have been only a little bit older when a photograph taught me what a mushroom cloud looked like; but once I learned what it was, that billowing image never left my consciousness, as I’d presume it’s never left anyone my age whose museum of memories seems just around the corner from consciousness.

I loved sci fi when I was a boy, The Twilight Zone an all-time favorite, Rod Serling’s voice more familiar to me than any preacher’s of the era. More often than not, the plots for that show presumed nuclear warfare and once in a while the mutants Serling and most others predicted another nuclear war would create.

Seventy years ago yesterday, we dropped "Little Boy" on Hiroshima, killing 80,000 people in a flash--and that's not a cliche. Eventually, twice that many died. It's difficult for anyone to get his or her head around numbers like that, and I won't try.

I wish no one had ever invented nuclear warfare. I wish there weren't something we can only call "the bomb." I wish we didn't have to argue about treaties with Iran or Israel or North Korea.

But any lament on what we did to Hiroshima and Nagasaki has to include stories I've come to know, stories of those I love.

In my grandparents’ home, a parsonage in Oostburg, Wisconsin, five stars stood proudly in the front window because my grandparents had five children in the war effort, my father being one of them.

My dad spent the war aboard a lousy tug way out in the South Pacific. He saw no action, but towed destroyers and tankers around harbors in islands he’d never heard of before he stepped on their beaches. He came home after those atomic bombs were dropped. After Hiroshima and Nagasaki, my mother greeted him in the Milwaukee railroad station on his homecoming. I can only imagine his joy upon returning. In his arms he held a little girl he hadn’t seen in two years and another he’d never seen at all. He was thankful, I'm sure, that he came home, as was my mother, as were my sisters.

My father-in-law spent two years just behind the Allied front as it moved slowly and painfully from Normandy to Berlin. He crossed the English channel a week or so after D-day, and worked in the motor pool, a kind of mobile service garage for jeeps and tanks and anything with grease and a motor. He and his buddies sometimes heard gunfire, but were never in anyone's crosshairs, never shot a rifle themselves. Their dirty hands held grease guns 24/7.

He had his orders in hand when the fires in Europe ceased. He and the whole bunch of gear heads were bound for the war in the South Pacific when the Enola Gay took flight. Because it did, he went home to the farm, to the horses. One of his brothers never did come back.

My father-in-law was single, but two years later he married a woman who’d lost her fiance on June 6, 1944, when he took a German bullet just one step off the landing craft at Omaha Beach.

In 1945, two of my uncles, research chemists, were employed on the Manhattan Project. For me and my family, their participation was a matter of great pride. Both men, gone now, were wonderful human beings. One of them served as the President of Westmont College for decades. The other chaired the Chemistry Department at Indiana University, but eventually moved into administration and actually served as interim President for a year when the Board needed more time to choose someone new.

My uncles were heroes to me, not because they worked on the atom bomb, but because they were warm and loving--and they were warm and loving Christians.

Not long ago, I was given a church bulletin from the First Christian Reformed Church, Orange City, Iowa, a bulletin from 1944 that included a list of names of the congregation’s “boys” in the armed forces. First Orange City was a big church, not mega, maybe 200 families back then; but it sits in the middle of a rural community where some kids got deferments because someone had to grow food.

Nonetheless, there were 35 men listed as serving their country in 1944, 35 men, some of them married, some of those with children. Think of your church without 35 of its members, all of them in uniform, most of them in danger. The cost of that war goes beyond anything most of us can imagine today.

I say all of this not because I disagree with those who curse atomic warfare and not because I can’t feel something of the immense anguish or horror that was Hiroshima. I'm probably closer to pacifism than anyone in my family.

I wish the world was an easier place to live, wish the answers came more easily. But this vale of tears isn’t an easy place for big questions, and the perfectly clear answers rarely are.

Images of what destruction we created in Japan are numbing really. It's easier somehow to forget that there were other stories, millions of them, my story among them.

And I'm thankful for that story too, thankful for growing up with a father.

4 comments:

I would encourage you to consider the number of lives the "A-bombs" saved by ending what could have been a protracted war with many more lives lost...

Forgotten British Heroes (Chapter 1)

This is also the date of some more hardships

I'm glad for this post because, as a Canadian who teaches high school history (as well as English), the atomic bombs sits on the curriculum as something we Canadians study without much passion. We're not connected to the event the way Americans are. I tell the students stories about the numbers Truman was shown--this many U.S. soldiers wouldn't die if the war ended quickly--and the kids just listen, passive recipients. Thanks for the connection to your own families' histories, Jim.

http://shop.americanfreepress.net/store/p/627-ATOMIC-BOMB-SECRETS.html

There seems to have been a problem with the archives at the Smithsonian.

Post a Comment