It was a joy to visit Ft. Laramie, not because it's such a flashy attraction--it isn't. My guess is that, this summer, the old fort won't gather all that many visitors because very few people would think of visiting an old fort that's a long ways away from nowhere.

But so much history--so much really significant history--happened there that not talking about the place and remembering its stories seems a pity and a shame, a pity because so much history happened there and in the neighborhood, a shame because some stories we'd rather not hear, but should.

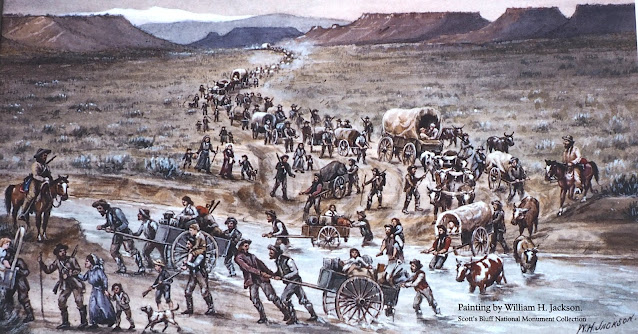

Purely American themes run right through the place--the place and power of government and legislation; the pain of bigotry; the possibilities of heroism; the use and misuse of natural resources; and all of it planted on the roughshod Wyoming prairie in a land where a herd of bison might stop a wagon train in its tracks for three days. Fort Laramie, Wyoming, is a place where, in the 1850's especially, almost any day of the summer, the parade of wagons and families, of single men, of pious Mormons, and starry-eyed dreamers were all on their way west, as if out there somewhere beyond the big blue sky lay heaven itself.

Between 1841 and 1866, 350,000 people moved west--and sometimes back east--and stopped--you just had to stop--at Ft. Laramie, just west of the Platte River, the four corners of the west. As a fort, it seemed once upon a time and yet today quite deliberately undressed. If your thinking that kind of big screen fortress, it's not a wrong-headed idea, but what's there today wasn't fortified by 20-foot timbers buried on end.

It started out as a fur traders' cabin, a rendezvous to rendezvous. Wilderness men with French names and Native wives would stop to eat and drink, to drop off the bounty they'd trapped through the winter, rest from the isolation of frontier life, and get themselves royally plastered.

And, later, more. At Fort Laramie American pilgrims could exchange draft animals, swap their own, worn and tired with aching feet or broken hooves, for another pair or two or three who'd been allowed a sweet vacation in grasses somewhere nearby.

Once upon a time, real live people had themselves a fling or two at Fort Laramie--sometimes hundreds were here, a mobile city, one of only a few such road houses on the great high plains. Ft. Laramie, a quiet little museum of a town, was once a giant fuel station with a convenient convenience store.

It was a reprieve, a comfort station, and people were happy, a hundred fiddlers spun out a hundred songs from dozens of "back home" in Scotland, Germany, Switzerland or any of a dozen other countries. After all, they'd made it to Ft. Laramie, to a place they knew was close by the tracks of ten thousand covered wagons through sandstone ruts most everyone had to take to get through to the mountains, ruts dug permanently by yet another step of the journey toward Oregon or California, or Utah. All kinds of folks--con men and preachers, regular folks with families, and unending flow of Mormon handcarts lugged along westward.

Those Mormons get the first nod of the story I'm telling, not because of their religion or the way they wouldn't let the fallen go without preaching them into heaven or hell. The Mormons are the first act because it was a Mormon cow that started the ache, the hurt, that opened the cut that led to bleeding.

Most of our stock footage of the west comes from movies in the mid-20th century, John Wayne and Ward Bond and the Lone Ranger. Prairie schooners were, for the most part, smaller than they might exist in your imagination; while the trail itself--the Oregon trail--is almost more likely to be far bigger than you might believe--and much wider. While wagon trains may have seemed out dangerously alone out there on the high plains, for safekeeping they often trailed each other by a mile or two or five.

Let it be said clearly that Native attacks on wagon trains were, in many ways, the least troublesome or worst danger. On long trips across the continent, far more children and parents suffered and died from diseases like cholera or swollen rivers. While Native bands may have been most feared, their place on the list of real dangers lie far beneath others--even snake bites or animal attacks outnumber them.

What's left of Ft. Laramie today is a museum, with a fine collection of well-preserved shops and offices and bunks the size of college dorms, enough anyway to hold a presence. What's not here is the history that once made the place the most thriving stop on the Oregon Trail.

Tomorrow's first act was created by a rundown Mormon cow. It's amazing how that beat-up old cow altered the lives of thousands.

.JPG)

No comments:

Post a Comment