It would be dead wrong to assume that that belief or any other created by the Messiah craze was the single cause for the horror that happened here in December, 1890. Others are far more prominent: the disappearance of the buffalo, the unceasing trek of white settlers onto traditional Lakota land, a long history of broken treaties, distrust on every side, the searing memory of “Custer’s Last Stand,” and, perhaps most of all, the inability of two peoples to understand each other. When you look down on the shallow valley of the Wounded Knee, bear in mind that what happened here is the confluence of many motives, some of them even well-meaning, but all of them, finally, tragic.

Here we are. Look around. If you stand on this promontory in the summer, the heat can be oppressive; but on a good day you might be surrounded by a couple dozen tourists. That’s all. Wounded Knee doesn’t exactly border the Black Hills, and it’s not on the way to Yellowstone. It’s not on the way to anything, really. Right now you’re in the heart of fly-over America, many millions of Americans never coming closer to this shallow valley than, say Chicago. Any time of year, the twisted vapor trails of jets on their way to LAX or LaGuardia float like ribbons in the genial sky.

In the late fall or muddy spring or cold mid-winter—like that December day in 1890—it’s likely you’ll stand very much alone at Wounded Knee. Cars and trucks navigate the reservation roads that cross almost directly at the point of battle, but for most of the year a visit here is unlike a visit to any other North American historic battlefield.

Gettysburg National Military Park offers an aging but impressive Cyclorama, a remarkable circular painting, 356 feet by 26 feet, that puts visitors at the heart of the battle. Little Big Horn’s visitor’s center sells helpful interpretive audio tapes to use as you tour several miles of battlefield from the air-conditioned comfort of your mini-van. But if you want to know what you can about Wounded Knee, the only storyteller there, all year round, is the wind.

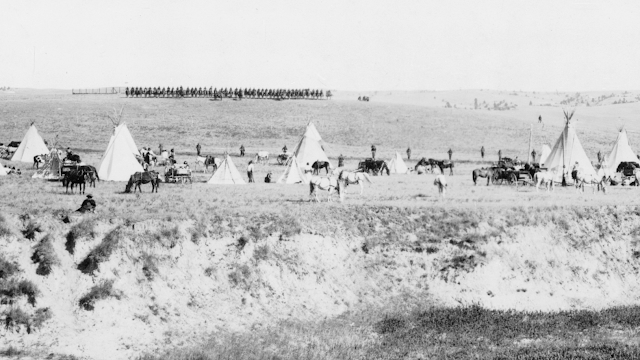

Just imagine the encampment before you, and keep in mind the despair, the poverty, and the hopelessness of the dancers. “To live was now no more than to endure/The purposeless indignity of breath,” says John G. Neihardt in The Twilight of the Sioux. Millions of buffalo once roamed here, the staple of existence for thousands of nomadic Native people, the soul of their culture and faith. By 1890, they were gone. In North Dakota’s horrible winter of 1996, while thousands of cattle died in the monstrous cold, it is reported that only one bison perished.

Once the buffalo ruled here. In all the openness all around you, the Great Plains stretching out almost forever in every direction, try to imagine what it must have been like to stand on this promontory and look over herds so large you could see the mass ripple as they shifted slightly when detecting human scent, like watching wind on water. That’s what’s gone. To the Sioux, the hunt was not only manhood’s proving ground, but a celebration for the family, often opened and closed with prayer. Few 19th century wasicu could understand that the disappearance of the buffalo seemed, to many Plains Indians, almost the death of god. I don’t believe I still can, try as I might.

But if I stand here on the promontory at Wounded Knee and remind all that is white within me of grinding poverty, the exhaustive dissolution of a way of life, and the seeming death of god, I can, perhaps, begin to understand the frantic hope inspired by the Ghost Dance.

2 comments:

Joseph Smith fathered the first American religion 70 years earliier.

Does anyone know about Mormon-Native relationships in Utah through the ninetheenth cenetury?

I met a former Mormon who who talked about Mormons cooperating with a group of Paiutes.

https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/mormons-and-paiutes-murder-120-emigrants-at-mountain-meadows

thanks,

Jerry

Post a Comment