I'm guessing it was forty years ago now that Chaim Potok, a Jewish novelist who'd acquired quite a reputation among American evangelicals (we were a different bunch back then), paid a visit to Dordt College. I know, that statement sounds as fictional as Book of Job, but he did. He was here. I know. I was there.

At the home of the President of the college, the English department and our guest, Mr. Potok, were invited for dinner one evening. Whether it was over dinner or after is immaterial. I have no idea how it was we were chatting about scripture, nor do I remember anything of what was said other than one darlingly devilish remark he made about the Book of Job.

He wore a wry smile all the way through the line. "You can't help but wonder," he said, "whether the writer created the ending just so he could get his story into the canon."

We all giggled. I still do. It was a level of spotten that would have been impossible to get away with as a Dordt prof, but Mr. Potok meant it in good fun, even if it landed well outside of the boundaries of orthodoxy. But, Potok was Jewish, we reasoned, and Jewish folks have a whole different view of scripture.

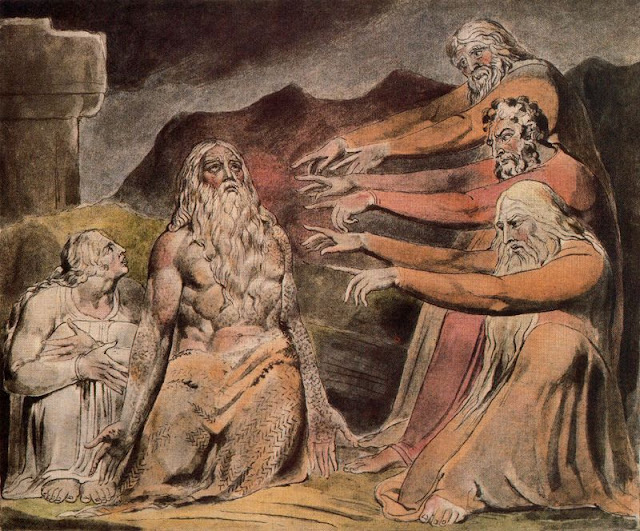

What he meant, jokingly, was that whoever wrote the fiction that is the Book of Job understood very well that all that bickering and belly-aching required an ending that would please the editor--the Almighty, and that what's there--Job gets chewed out for the preposterous notion that he can understand God--is something that simply had to be. What the statement suggests is that the ending is tacked on in order to get some wholesome sales. That assessment was shocking, like the ending itself, which is far more scary than nice. Job was minding his own business and doing it with a credible righteousness when God almighty hung him out for Satan to do his dirty thing.

After endless theological bickering, the writer finally brought in the voice of God to say that if you think you can have a personal relationship with the cosmic power that He is, you're sadly, tragically, mistaken. Be still and know--that sort of thing.

I've never forgotten that assessment, I suppose because something about it sounded as accurate as it may have been errant. Scripture was divinely inspired, I'd always been taught, as if God himself were narrating the text. Way back in grade school, I used to think that God turned himself into ink and flowed right into and out of those feather pens the ancients used. To think that some mortal writer was doing the story-telling, fashioning the book to his own ends, was heretical. But cool.

But I liked it and still do, especially after, once again, reading most of the book aloud, in chunks, and listening to a month of Job sermons. I can't help but wonder whether scripture doesn't do a better job of helping us understand ourselves than it does of truly "understanding" God.

I can swear to his reality, know he loves me, treasure his morning canvases, the sophisticated beauty of his creative work all around. I can believe He sent his son to this earth to fashion a way of living in accordance with all he wants of us and for us, but I'll never understand him. I'll never know it all.

And if that's true, then, like Job, I'd better just keep my mouth shut--or at least learn when and how to complain.

All of which makes me more comfortable with the notion that, like the Book of Job, Holy Writ is really a record of what man thought about God. It seems impossible to believe that the lamentable story of Job actually happened. It has to be some writer's concoction. Some anonymous writer created a story to help him (and us, finally) know something important about God.

There are times in our lives--don't I wish this weren't true?--when we can't help but think we're in Job-level quandaries. When we are and when we do, this strange fiction is a model, not even necessarily the model, maybe not even a good model, just a model. The Bible tells us repeatedly, "Been there, done that."

Butchered the enemy, even their women and children, oxen and mules? Sure. Been there, done that. But a massacre certainly is not the model. Banned women from speaking in church? Sure. Been there, done that. But that's not the model.

At times, it seems the psalms contradict themselves, but those contradictions don't prompt us to dismiss them as scripture, as Holy Writ. They merely offer us means by which to try to do our express human work: to live in His rule.

The Book of Job is what one writer wanted to say, his view of things. Is it Right (upper case R)? That's a question not worth asking. The book is there. It's in the canon. It made the cut. It's less "Right" than it is "Good." It's a bad story that's good for us, even if we throw in the towel little more than halfway through, even if we know how it ends only because we cheated or the preacher told us.

It's Holy Writ and human writ (not upper case), sometimes far more the latter than the former.

I dare say loads--if not all--of our endless theological bickering is attributable to our varied understanding of the nature of scripture. On that score, I'm hardly an expert. Want one? You can find them by the dozen in varied hues.

"Consider my servant Job," God says, as does the writer. After my own due consideration, I'm just saying what I can't help but think about what's in the Book of Job, even if I cheated and skipped to the end.

1 comment:

Some scholars do think that the introduction and conclusion to the Book of Job were written by a different author than the main body of the the book, because they seem so different.

Interesting comment by Chaim Potok, I've enjoyed reading a few of his books.

I do think that the Book of Job is worth reading, and I'm glad it's in the canon. And yes, it is both Holy Writ and human writ, that's what makes it so inspiring, insightful, puzzling, and interesting.

Post a Comment