And all of that Christian fellowship, she says so emphatically, happened within sight of the very place on the Big Sioux River where she had stood witness to the horrible death of her companion in captivity—19-year-old, pregnant Elizabeth Thatcher:

Does all of that make Ms. Gardner’s book a better memoir? I don’t believe so. Massacre and Captivity still feels uneven, strangely disjointed, an awkward mix of horror and beatitude amid a file drawer full of historical reports, and a memoir that may well be withholding some of its own secrets.

But this reader, so many years later, finds it much easier to understand the memoir as a Christian “testimony” than a captivity narrative; and so may others, especially, I suppose, those who share Abbie Gardner’s faith in a person she describes as “the living Christ.”

I’d like to believe that Abbie Gardner’s memoir describes a very specific place in Flandreau, South Dakota, just up the hill from town where, today, stands “the oldest continuously used church in the state,” or so the sign out front says—River Bend Church. The building was constructed in 1873; the original structure still stands on the grounds of the Moody County Museum, in Flandreau.

River Bend Church sits quite reverently away from things, a quiet and beautiful place. A cemetery, which stands just west of the building, tells its own incredible stories, gravestones etched with Bible verses in both English and the Dakota language.On an elevation about one mile north of town. . .a charming view can be obtained of the picturesque valley of the Big Sioux. From this point I beheld a promising young city (named in honor of the man who conceived the plan of my rescue[1]), two Indian churches, and the river where I stood on the bridge of driftwood and witnessed the death of Mrs. Thatcher some thirty years ago.Standing there before the church at Flandreau, she was so close to that riverbank, she claimed she could see the place where Mrs. Thatcher was beaten to death in the swirling rush of water:

The past and present scenes rose up and passed before me like a living, moving panorama, and the change that had come to pass on the stage of life seemed truly marvelous. We attended the services in these churches, listening to impressive sermons, delivered in the Sioux tongue, to large, well dressed, and attentive congregations. What had once seemed an impossibility, had become a living reality—a body of Sioux Indians, with religious thought, congregated together to praise Him whose name is Love!Some readers may have anticipated the publication of her memoir as yet another “captivity narrative.” Those readers couldn’t help but be disappointed because Abbie Gardner could not tell her story accurately without the stunning moments of reconciliation at Flandreau. She wanted badly to claim she’d been healed of those maladies that kept her an invalid, freed by her belief in Jesus. For that woman, standing in the circle of men and women who could have murdered her family, men and women she knew to be mutual sufferers, then professing their mutual faith was a “truly marvelous” event unlike any she says she could ever have imagined. It is a stunning moment.

Does all of that make Ms. Gardner’s book a better memoir? I don’t believe so. Massacre and Captivity still feels uneven, strangely disjointed, an awkward mix of horror and beatitude amid a file drawer full of historical reports, and a memoir that may well be withholding some of its own secrets.

But this reader, so many years later, finds it much easier to understand the memoir as a Christian “testimony” than a captivity narrative; and so may others, especially, I suppose, those who share Abbie Gardner’s faith in a person she describes as “the living Christ.”

I’d like to believe that Abbie Gardner’s memoir describes a very specific place in Flandreau, South Dakota, just up the hill from town where, today, stands “the oldest continuously used church in the state,” or so the sign out front says—River Bend Church. The building was constructed in 1873; the original structure still stands on the grounds of the Moody County Museum, in Flandreau.

It just seems fitting that even the much-hated and much-loved Dakota headman Little Crow is here too, in peace, in a far corner.

If you stop sometime, you’ll almost certainly be alone. But I’m guessing that’s where Abbie Gardner stood one day in September, 1892, and saw before both her death and life in a vision something akin to a new heavens and new earth, on a day she calls her “Day of Realization.”

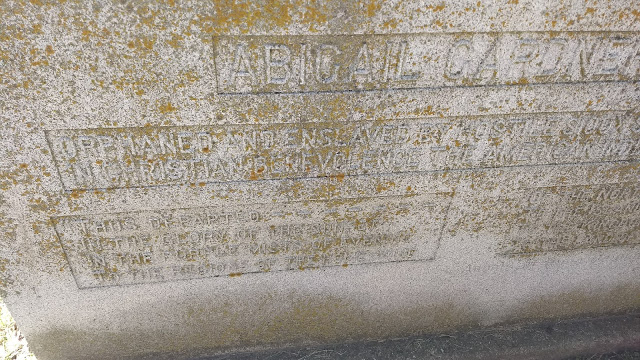

It is unlikely that anyone will ever know who wrote the epithet on the stone over the grave of Abbie Gardner Sharp, if she did not. It sits just a few steps east from the cabin where Abbie lived just a few decades after watching her family murdered right there. The words on the stone speak to a similar place in the human heart, a place she would have called “the soul”:

ORPHANED AND ENSLAVED BY HOSTILE SIOUX SHE LIVED TO EMBRACE

IN CHRISTIAN BENEVOLENCE THE AMERICAN INDIAN AND ALL MANKIND

No comments:

Post a Comment