The decision is inevitable--it will be made and, likely, soon. Hundreds of volunteers painstakingly winnow through tons of debris. No earthquake, no hurricane, no bombing brought down Chaplain Towers South, and there was no real-time warning; but soon, a decision to change what's happening in the horror will have to be made.

Search-and-rescue will cease. Clean-up will begin. The score of loved ones now cowering in hope and fear just down the road will shed even more tears. Loved ones' remains will be trucked away with an eternity of concrete and rebar, all of it broken. So much that is precious will go to the landfill.

Consider the loss.

At Good Earth, it's almost impossible to believe what the signs assert. When you look out over the swatch of river bottom to the east, you'll see an ocean of gorgeous emerald in a winding river valley, but little more. There's land out there just yearning to be developed, good land just outside one of the fastest growing municipalities in America, Sioux Falls, South Dakota. But it's not--it's lovingly being preserved.

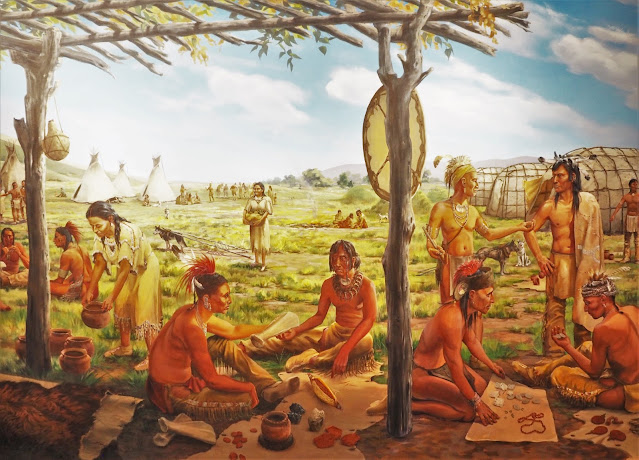

Once upon a time, a city lived and grew right there, a city 10,000 residents strong, the Indigenous scholars call the Oneota. For hundreds of years ordinary people lived and worked here, lived and died here. When there was no Chicago, the Good Earth was here. Before Boston, there was a city on the Big Sioux, a trading community that drew America's First Nations from near and far by way of the soft red stone available here and only here, pipe stone.

The Oneota were ancestors of tribes later named the Ioways, the Omaha, the Ponca, and the Otoe. Once there was a city. If you visit today, it's amazing how little can be seen. If you hike down toward the river on the gravel paths, you'll see some wild life maybe, hear some birds, and walk through lots of prairie being renewed, brought slowly back to the colorful tangle of native flora that once existed here.

Mr. Frederick W. Pettigrew, a son of Puritan New England in a fiercely committed abolitionist family, created a map of what he called "the Silent City" when he lived here in the 1880s. That map offers out best view of what was once here.

No comments:

Post a Comment