But then Curtis Harnack learned farming from a man whose heart wasn't in it. When his own father died, Harnack's mother chose to stay on a farm that would be run by her brother-in-law, someone she determined would be the kind of father-figure her son would need. Uncle Jack figures greatly in We Have All Gone Away, although their relationship is somewhat love/hate, in part because Uncle Jack never really loved the chores that come with the territory and would have greatly preferred what folks used to call "tinkering."

But 'druthers' weren't in the cards during the Depression, when Curtis Harnack was a boy. Uncle Jack had no choice but to farm two chunks of land that came to him when his brother-in-law died. Harnack may well have picked up something of Uncle Jack's own disgruntlement because while the essays in this thoughtful book of memories are redolent with farm memories that are anything but disdainful, Curtis Harnack determined early on that farming northwest Iowa soil, as rich as it might be, was not going to be his lot in life.

His mother wanted more for her boy; and that, he says in the book, is the reason he had no choice but to leave. His mother looms over this memoir like no other character, even thought she remains mysterious and shadowy. Halfway through, I wondered why I knew so little about her. By the end, we know her better; but one of the most intriguing aspects of this wonderful series of essays is that it is so much about a woman we never really come to know.

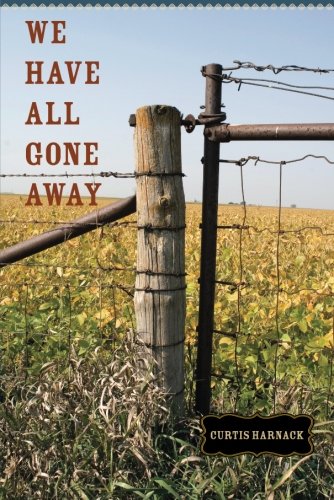

I'm not sure Harnack knew her either. She was always there at home, but what these elegant essays say more clearly than anything was that she reared her talented children (and they all were talented) to leave the farm and Remsen for worlds that didn't end at a fence row. We have all gone away, Harnack says, because that's the way mother wanted it to be.

Caroline Harnack died in a mental ward in a Sioux City hospital after attempting suicide twice. If he didn't really know her, it's possible no one did. But what Mother Harnack clearly imparted to her children was the necessity of finding themselves in a larger world than Remsen.

So long as Mother could anticipate the unfurling of events in the lives of us children, her spirit was sustained; she was held together merely by being a witness of destiny. But once the true patterns became evident, and the playing out of our years meant we'd actually be more and moe removed from her, a weariness and hopelessness about her own remaining years descended. What was there left to envisage, in her future? Somehow, she'd imagined getting away, too, just as we were doing, but she wouldn't want to be an encumbrance, hang onto us, or interfere in our lives. we were to go off by ourselves without so much as a glance back; otherwise how could we create our lives to their fullest extent? She knew at last the clean, scraped-womb condition of her sacrifice to give us our chance.

I had no trouble putting down Curtis Harnack's short story collection Under My Wings Everything Prospers because I thought I was listening to a man with an identity problem, someone who wanted badly to be something he wasn't, someone who wanted to be something distinguished and academic and exceptionally literary--and not from the farm. Some of those short stories feature characters he didn't seem to know, and there's a mannerism to the writing that suggested he wasn't writing from the soul but for readers whose regard he wanted more than anything. I had trouble finishing the stories.

On the other hand, even though I was taken with the first essay in We Have All Gone Away, not until the end of the book did the book's strengths fully take me over. At his worst, Harnack tries too hard for a sophistication he is more than capable of achieving--he's a marvelously graceful writer. But art for art's sake doesn't work all that well in a book about the farm where he grew up.

Like a growing season, We Have All Gone Away is a collection of memoir essays you slowly come to love. By the end, you start to feel they're almost perfect.

I've been on a kick for quite a while, reading books that grew up in the region. Harnack's We Have All Gone Away is one of the very finest. It's artful and literary and not for everyone, but it's beautiful in its design and almost perfectly lovely in its mystery.

Willa Cather had designs on leaving Red Cloud, Nebraska, behind her on the path to literary stardom, when a friend reminded her that Cather knew great stories from her Great Plains past. Thank the Lord for good friends. We've got Song of the Lark, My Antonia, O! Pioneers.

I wonder if something similar, somewhere along the line, didn't happen to the New Yorker Curtis Harnack became. Someone may well have suggested the Iowa farm boy write about Remsen.

And he did.

No comments:

Post a Comment