He told me he was in his last year of college when it happened. He said he had signed up for an interim course in Native American history taught by a visiting prof and offered because the history department had no such course on its books. He signed up joyously, he said, because he was and is Native himself, Navajo.

When that three-week course was over, he dropped out of college he told me, because what he learned about his own history was so shocking that he grew very angry. He'd never known his own history, never been taught much about millions like him who'd been here long before Europeans swarmed the continent. In 20 years of education, much of it in Christian schools, no one had ever laid out his own racial and cultural past.

He laughs when he tells the story now, forty years later, not because that anger was trifling but because he is very much at home with himself and his history; but Native American History, a three-week course, an elective, pushed him to see the world around him, on the reservation, in a way no other class ever had.

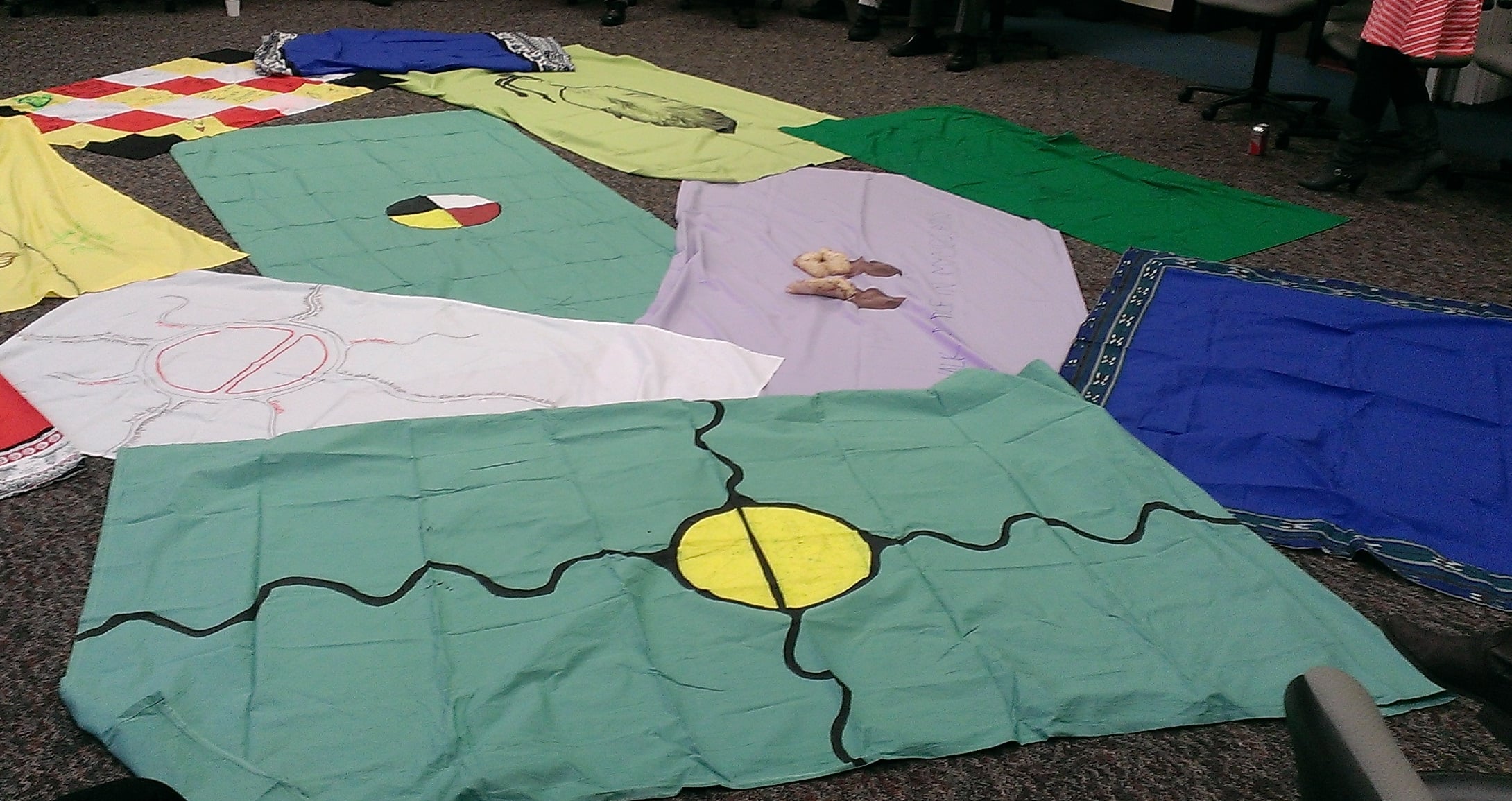

Last Sunday at a local church we learned something about Native American history in a simulation titled "The Loss of Turtle Island." As everyone knows, the winners gain the rights to tell the story, and that's clearly evident in the way history comes to most of us. Most Minnesotans probably knew very little about the Dakota War of 1862 until the 150th anniversary just a few years ago, even though the massive bloodshed on both sides of that conflict created an event staggeringly important in the state's early history.

Most of us would rather not know those things. Where I live, we'd rather call the region we live in "Siouxland" than know about the Sioux. Most white folks are saturated with the notion of our own vaunted sovereignty. It's even a religious thing: we are, after all, "a city on a hill," awash in happy talk of "American exceptionalism."

"The Loss of Turtle Island" is a sobering examination of our national past that modestly lays out a history which begins, at least legislatively, with a papal bull drawn up in 1452, a doctrine which encourages Christians like Columbus to

…invade, search out, capture, vanquish, and subdue all Saracens and pagans whatsoever, and other enemies of Christ wheresoever placed, and the kingdoms, dukedoms, principalities, dominions, possessions, and all movable and immovable goods whatsoever held and possessed by them and to reduce their persons to perpetual slavery, and to apply and appropriate to himself and his successors the kingdoms, dukedoms, counties, principalities, dominions, possessions, and goods, and to convert them to his and their use and profit. (Pope Nicholas V)That's where it starts--the Doctrine of Discover--and it ends, presently at least, with an actual national apology slipped surreptitiously into “House Resolution 3326, 111th Congress, Department of Defense Appropriations Act, 2010, a seven bullet-point apology to Native people that contains no reference to any specific tribe or treaty or injustice, then concludes with a disclaimer stating that nothing in the resolution is legally binding.

This formal apology--it's part of the Congressional Record--was never announced, read, or publicized by either the White House or Congress.

Once upon a time, President Andrew Jackson ordered thousands of Native people from the American South to march west for a thousand miles to what he created as Indian Territory, the territory of Oklahoma. Many thousands died, and many thousands afterward. "The Trail of Tears" is not just a national tragedy; it was sheer horror. No white folks walking around barefoot on bunch of rugs in the fellowship hall of a church are ever going to know what it must have been like for those Cherokee, those Choctaw, all those men and women and children who were taken from long-established homes and sent to an ocean of dry grass.

Maybe we were kidding ourselves. We can't know.

But we can learn. And learn we did. By the time the game was over, most of the blankets were gone. Those which were not were bunched up into chunks a foot or two long and wide and separate from each other, like reservations. Most of the barefoot participants were off Turtle Island.

When my great-grandfather came to America in 1848, he and his wife experienced "the

hardships and trials of the early pioneer," his obituary says. They had "very

little to eat, not much clothing, and scarcely any of the comforts of life." In the forests of eastern Wisconsin where he lived, the obit says, "the

red men were still numerous. . ., but were not troublesome to the

white settlers, except as beggars."

Of course I have a role in this history. Of course, I do.

It's impossible to participate in "The Loss of Turtle Island" and not wonder what can I do? What do I owe?

I owe this much at least, I believe--to listen to those stories we rarely tell.

This morning I'm thankful for "'The Blanket Exercise" and stories it so vividly tells.

Of course I have a role in this history. Of course, I do.

It's impossible to participate in "The Loss of Turtle Island" and not wonder what can I do? What do I owe?

I owe this much at least, I believe--to listen to those stories we rarely tell.

This morning I'm thankful for "'The Blanket Exercise" and stories it so vividly tells.

3 comments:

Excellent piece.

I just came across this piece. Can you tell me who facilitated the "Loss of Turtle Island" simulation? Thanks!

supreme new york

yeezy 700

supreme

supreme official

yeezy gap

kevin durant shoes

off white

jordan outlet

jordan outlet

supreme clothing

Post a Comment