There was no good reason for General George Armstrong Custer

to ride into the Black Hills in 1874, but nefarious reasons abounded, including the determination of military higher-ups’ to set yet another fort in the Hills to

make sure untoward things didn’t happen to the multitude of white folks on their

way west.

Truth is, the Sioux reverenced the place. Think of it this way—if you vacation often in the Black Hills, the place begins to conjure memories of joy and love. Wander back sometime and you’ll suffer almost crippling nostalgia.

The Lakota held the place in even greater reverence because a spirit lived in residence therein, an old bearded man in a mountain cave that actually breathed. Paha Sapa wasn’t just a nice place to visit; it was divine.

To Custer, the only thing divine in them thar’ hills was gold. Hence, the 7th Calvary.

The generals knew it would be difficult to come into the Hills from the south, by way of the lands of Red Cloud and Spotted Tail, so they directed Custer and to sneak the 7th in from the north, a thousand strong, from Fort Abraham Lincoln.

The idea was not to fight, even though Custer bragged he could “whip all the Indians in the northwest.” Their mission was to find a place for a fort. Sure it was.

Three newspaper reporters and President Grant’s son Fred were along for the ride, as were two “practical miners” whose way was paid by Custer himself. In Augustof 1874, the "practical miners" were the real reason Custer was there.

Once the 7th Cavalry stopped to let them pan, it took five days to find gold; and what they found wasn’t a whole lot.

No matter. When Custer himself sent a cable, people heard the word gold and hopped the next ride west. "Gold fever" lit a prairie fire like none other. "Gold Fever"--a country just a century old suffered yet another full-fledged epidemic.

The 1848 California Gold Rush was—and remains—the largest mass movement of population in American history—300,000 people swarmed west even though there were no roads and no fast food.

Custer’s find, 25 years later, didn’t create the numbers that had left for California; but the sheer mass of money-mad folks changed the course of American history because white folks determined, then and there, that the Black Hills were a way too valuable to be left in the hands of the heathen Sioux. Just like that, another treaty bit the dust—not gold dust either.

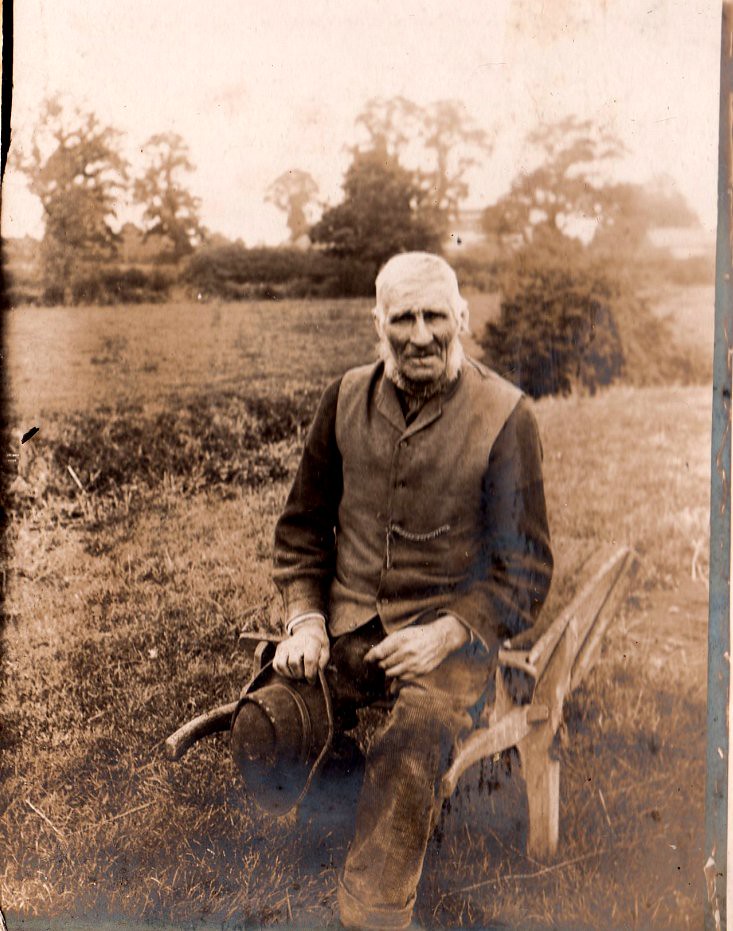

It's hard to believe anyone moving west in the hysteria people called “gold fever” ever considered the story of poor old D. C. Jenkins The many thousands saw nothing but a shiny nugget sifted from a pan of wet sand and, thus, themselves thereafter in the money.

D. C. Jenkins came east and homesteaded in Nebraska, after leaving the gold fields behind. He was entirely bereft of the fever he'd once suffered, pockets were empty, not even a gold tooth flashing from what few smiles he could muster.

Get this. Mr. D. C. Jenkins walked all the way from Pike’s Peak to Nebraska, lugging everything he owned in his wheelbarrow. Just imagine. Mr. Jenkins pushed that thing a couple hundred miles to Jefferson County, Nebraska, and started ranching.

Maybe a picture of D. C. on a post office poster could have prompted some to think twice about chasing gold dreams. Maybe a video: a grizzled old cowboy pushing a loaded wheelbarrow down the mountain and all the way to Nebraska.

Maybe.

Then again, probably not.

Get this. Mr. D. C. Jenkins walked all the way from Pike’s Peak to Nebraska, lugging everything he owned in his wheelbarrow. Just imagine. Mr. Jenkins pushed that thing a couple hundred miles to Jefferson County, Nebraska, and started ranching.

Maybe a picture of D. C. on a post office poster could have prompted some to think twice about chasing gold dreams. Maybe a video: a grizzled old cowboy pushing a loaded wheelbarrow down the mountain and all the way to Nebraska.

Maybe.

Then again, probably not.

No comments:

Post a Comment