My mother loved me--didn't hate me. My mother rewarded me, especially when I practiced piano. She spanked me once, although years later, when I wrote about that summer morning, she denied it (one of us was dreaming). I didn't grow up with a witch of a mother like Philip Yancey's, although I don't know that spiritually the two of them were much different. Had they ever met, their conversations would have joyfully carried references to the Lord's great love and their great love for Him.

Yancey's Where the Light Fell is his personal memoir of growing up, and it's rife with his mother's abuse of the boys she raised alone after the early death of her husband. The recitation is a horror, really, her behavior so vicious at times that you can't help but wonder how that woman could have raised a child who would become the world's most prominent advocate of grace. My mother--and maybe his--would stake out a claim for the Holy Spirit.

Yancey's story has givens that made me smile--like a reference to Watchman Nee. I remember something of the story from Christian school a hundred years ago. Nee, a Christian preacher, was imprisoned in his native China. He suffered for his faith, a martyr for our time. Philip and I, Christian kids on both sides of the Mason-Dixon, heard the same Sunday School lessons.

And those lessons included a now soundly rejected takeaway from the Old Testament, the story of Noah's sons, who pulled a fast one on him when he passed out from the Devil's brew. One of those sons, the Bible says--or so both Yancey and I were taught--was Ham, who was sentenced to Africa and a lifetime of servitude. Down South, where Yancey grew up, the theory of Ham was, for many, a biblical warrant for institutional slavery. How could you deny it?--the Bible said black people were sentenced to servitude. Can there be any doubt?

If I can go back to my own fifth or sixth grade--as well as nightly family devotions--"the theory of Ham" wasn't used to rescue slavery as an institution but as a means of understanding how poverty came to show itself in "colored" neighborhoods. Noah's son Ham--he's the one to blame, the guy who made it happen.

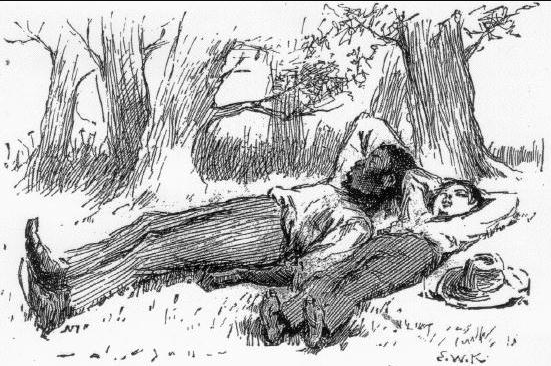

It's lost some steam now because of the frequent use of the n-word, but Mark Twain's great novel, Huck Finn, ends (or at least reaches a climax) when Huck tries to figure out what he's supposed to do with the runaway slave, Jim, someone he's grown to love. Should he turn Jim in to the sheriff or just keep moving on the river toward his freedom. What Huck's rugged, innocent soul is battling is a biblical injunction he picked up somewhere in "civilization," to wit, that obeying the law was somehow the same as obeying God. Somewhere down there in his soul was "the theory of Ham." Helping Jim run away was taking on the Bible itself, God Himself.

And that's why the most precious line in 19th century American literature is belongs to Huckleberry Finn: "All right, then, I'll go to hell."

One of the grandest moments of my college teaching career happened during my first two years, when I taught American Literature and had the class read Huck Finn. The class was huge back then, when it was required. I scrambled to find a copy of Catharine Vos's The Children's Story Bible, the one my parents used for family devotions, the one my teachers in Christian school used throughout those years.

And found it. There it was. The theory of Ham. Right there on the page. I made copies, handed them out--everybody got one--because I was sure that my students (late '70s) didn't understand the meaning of the blistering critique Huck lays on the society all along the river. "Well, then, I'll go to hell," is very much a theological declaration, a statement of faith and damnation of bigotry, racism.

I was just plain thrilled that I'd found it. I remember handing it out and going through the explanation I've just now been writing.

I don't know what I expected. What I remember of the moment, more than anything, was a sea of faces that showed little of my fascination, my joy. It was just, well, school--"is-this-going-to-be-on- the-test?"

I don't know that my mother would have been proud of what I did in class that day, breaking into student's psyches and souls to establish a beachhead for toleration they would have had trouble creating in themselves. I don't know that I was reflecting my parents' values that day; they might well have been, well, concerned. I'm sure Philip Yancey's mother wouldn't have bought in.

I have no idea if any of my students, so long ago, remember "the theory of Ham" from that a survey course in American Lit. The Children's Story Bible is still published, but no longer distinguishes the reference, thank goodness.

Right now, as the words appear on the screen before me, I can't help thinking my joy that day rises from my own pilgrimage as a very sweet epiphany.

"Want to understand what might be the most memorable line in 19th century American literature?--let me tell you a story from the time when I was a boy."

It was, I think, the kind of moment lots of righteous Republican legislatures these days think shouldn't occur in our schools because what happens in the classroom should reflect their students' parents' values.

Well, maybe--but then again, maybe not.

No comments:

Post a Comment