Morning Thanks

Garrison Keillor once said we'd all be better off if we all started the day by giving thanks for just one thing. I'll try.

Tuesday, March 31, 2020

Day #19

Here's what's going for us in the back yard right now--spring. Only once a year are we blessed with the gift of emerging life. These little guys will flower soon and then be gone, but for a week or so in late March they're numero uno, a religious spectacle, a processional of bright green thanksgiving.

Lord knows we need 'em. Last weekend, Dr. Fauci dropped a number into the virus dialogue that may take a week or more to register--200,000 deaths, at a minimum, if we're blessed. Just for record, a reader tells me that total annual deaths from influenza average between 20 and 60 thousand.

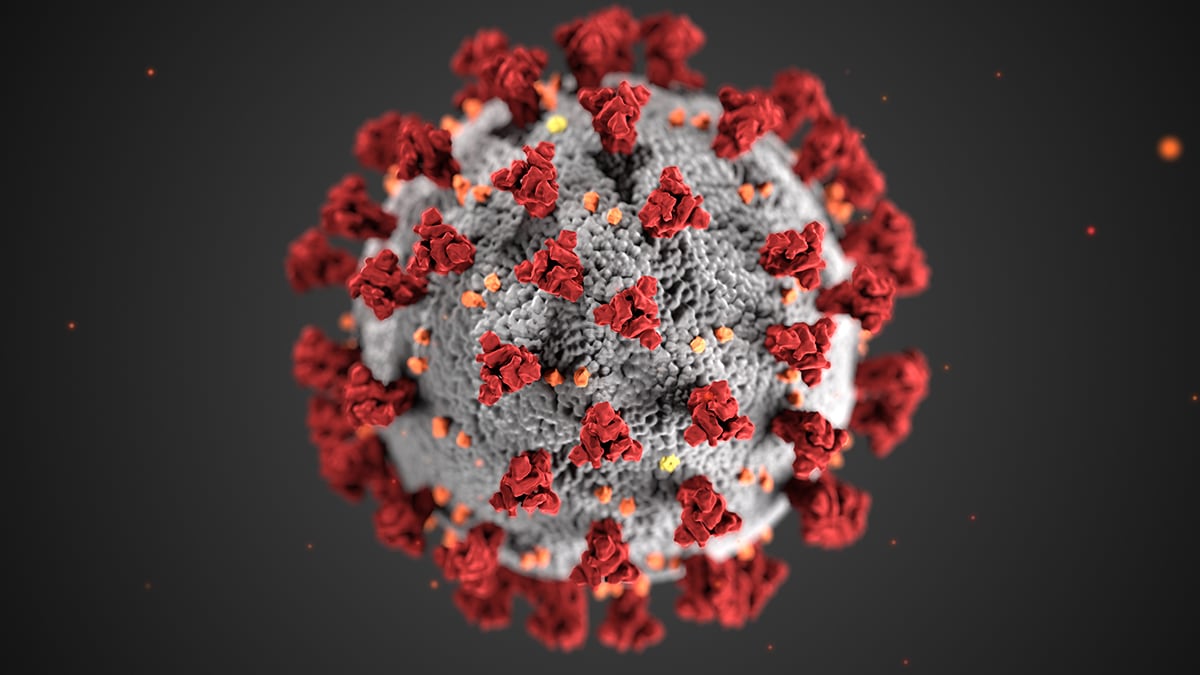

COVID-19 is a wholly different breed of cat, and 200,000 is a trial simply to imagine.

Impossible for us, a retired couple but not institution-ed. Like everyone else these days, we video-called (FaceTime) our kids just a dozen miles away. "Can we come over?" our granddaughter asked. She's in college, except she isn't right now. A soft answer turneth away wrath, I guess, but how do you say, "No, you can't" sweetly? Her brother, a high school kid, told his mother he was jumping from the roof tomorrow. Stay tuned.

For some, like us, life goes on.

We went a dozen miles south for a river walk (wonderful, but nothing like San Antonio). We'll do that again because the path was, for us at least, new and as beautiful as the sunny morning. I grew up with hardwoods on the lakeshore, but out here at the edge of the plains, I've been really taken by cottonwoods, not because they're gorgeous but because--forgive me!--they're not. Look at this car wreck.

He's a monster. But then, who knows how many floods he's seen? How much wind? How many twisters? He's as formidable as he is mangled. Maybe it's a her. Wood so soft that most farmers out here on the ocean of grass called 'em weeds. Still, in no time at all this beast will draw a quilt of emerald over most of its nakedness.

Call 'em what you want, I call 'em survivors--huge survivors whose towering ugliness is somehow astonishing.

Beating COVID-19 is going to require a level of American exceptionalism we haven't needed for many years. . .long riverwalks of patience and compassion and sorrow.

In just a couple of weeks, if that, this old cronie will blossom, God willing. Come July heat, it's old, broken arms will spread soft shade over the river walk.

That's something to look forward to too.

Monday, March 30, 2020

Day #18

I'm calling it Day #18, because the day I couldn't help thinking all of the virus-hex was deadly serious was the day the NCAA tournament was shut down, redefining "March Madness."

If it's Day #18, then it seems fair to say that the last 14, have been, here at least, awful weather-wise. Not wicked, just awful--wind and clouds and gloom. But yesterday we caught a break: it was a very real Sun-day. The wind abated, and the Puddle Jumper Trail was full of people (keeping their distance). When I got out there, it seemed far warmer than I thought it would be. I couldn't help thinking that what we'd missed in that cloudy cold was the actual death of a season. There's actually green stubble out back, gorgeous stubby stands of emerald. I can't remember ever being surprised by new growth before. Amid the dark cold, what was lost to winter grabbed a wholesome jump start. It's still kind of dark out. Later, I'll grab a picture of that green goodness.

Yesterday, Fauci the flu guru bare-knuckled a somber prophecy: we could lose one hundred to two hundred thousand before this vampire virus gets laid to rest. Astounding. I want badly not to believe him. That was a conservative estimate too, assuming we all keep our distance.

Honestly, no one's got it as good as we do, a couple of retired folks out here alone in the country, rour schedule less than bare-minimum-ed. We worry about our kids, especially the little Oklahoma cowgirl about to be born.

Want to know how many options a person had to attend worship yesterday?--just as many as one has any ordinary Sabbath. Everybody's worshiping on line. Yesterday, we had church in the basement again, week #2; but someone had taken note of the bare naked look behind the preacher last Sunday and thusly put up some props that definitely improved what we might call "the set."

I'm guessing that setting change illustrates community-wide adoption of the demands experts and the Pres claim must be followed. We're learning to adjust to the isolation, sheltered in place. It's not fun.

In a half-hour or so, I'll be on the radio, talking about the Spanish Flu a century ago. I don't want to listen.

Time to quit. Out east, the morning sky is a bit carmelized beneath an azure bowl that promises good things. It's beautifully calm and clear. Look for yourself.

That'll do. This morning, I'm thankful for another dawn.

Sunday, March 29, 2020

Reading Mother Teresa--"I thirst"

“I am thirsty.” John 19:28

Sometimes people here in the upper Midwest claim we’re blessed with only two seasons: winter and Fourth of July. The line works, I think, for two reasons: one, winters can be brutal; and two, so can Fourth of July.

When we moved to Iowa from Arizona, we didn’t expect to be clobbered by heat, but we were. The house we rented was not air-conditioned, and, that first July, we nearly died – that’s overstatement. What we’d left was higher temps, but what we’d discovered was thick, dank humidity.

Right about now, mid-summer, nothing dispatches thirst like lemonade. Pink, white, raspberry – no matter. It’s a reminder of a boyhood bucking bales when icy canning jars full of the stuff were the only antidote to heat stroke. That’s overstatement too. You just get thirsty, really thirsty, in July haymows.

We just finished a sojourn in New Mexico, where we hiked over murky lava flows and through elegant sandstone at elevations that sucked your body dry. Always pack water. Drink it--parks and trails at 7000 feet don’t pussyfoot; their signs use the command form. Water is life. I drank buckets.

I’ve spent most of my adult life believing that if we underplay anything at all about Jesus Christ it’s his human side. The great mystery of his existence is that he was, at once, both God and man. Impossible, yet there he is, both. Where we underestimate him, I’ve often thought, is in his humanity. We like him as Lord and Savior, but he could be almost unfeeling at times – witness his seeming disregard for his own mother when he started out on his own in the temple. If you want to follow me, he told his disciples, forget Mom and Dad – actions he modeled himself.

He was human. Jesus Christ was human, too, not just Lord and Maker and King and Redeemer. He pulled human flesh as if it were spandex, for Pete’s sake – and mine.

Therefore, “I am thirsty” is an utterance I’ve often considered to be a clear indication of his humanity. The physical agony of the cross, far beyond my imagination, prompted very human needs – he got thirsty, horrifically so. He was human. Be careful, I might have said – and still would – about over-spiritualizing him.

Then there’s Mother Teresa, whose very ministry was created – by her own account – by her immense interpretive vision of that very Good Friday utterance – “I thirst” (41).

Why does Jesus say “I thirst”? What does it mean? Something so hard to explain in words – . . . “I thirst” is something much deeper than just Jesus saying “I love you.” Until you know, deep inside that Jesus thirsts for you – you can’t begin to know who He wants to be for you. Or who He wants you to be for Him. (42)

That’s what MT believed.

Jesus Christ was Mother Teresa’s sole motivational speaker, and his words, especially those uttered in his agony, were her rallying cry. She transformed his thirst into a metaphor and spent her life working to quench the emptiness he felt at Calvary, an emptiness satisfied only by the poor – their love and their souls. His thirst for them became her soul’s motivation.

She saw Jesus dehydrated, wearied, nearly dead; and she sought to bring him relief on the streets of Calcutta by satisfying his thirst for those poor he loved so greatly.

It may well be I’ve been wrong for all these years. Perhaps in stressing his humanity, I’ve neglected his divinity. Perhaps in taking him literally, I’ve not seen him spiritually, up there on the cross at Golgotha, body and soul dehydrated, his heart overworking to pump his dehydrated blood because he wants, more than anything, not just water but, as MT might say it, those he loves, his people, splashing over him, gushing with love.

That’s the way she read it, and that’s the way she lived in Calcutta.

Something to consider, even in our muggiest July.

Friday, March 27, 2020

It's precious

My memory has him at second base. I don't know if that's right or not, and if my memory fails me, I'd not be surprised. I just remember him showing up out of nowhere with the whole gang of public school kids, coming up the hill to the east diamond on the playground cross from our school, the Christian school.

There were no adults. Just kids. Sixth graders, I think. And he and the public school kids came over in a wave, kids we knew but mostly hated because they were the enemy, not Satan's minions, but ball players with some ringers who made them tough to beat. The whole bunch of us--Christians and publics--were on our own. Not a teacher to be seen, not a parent either--just kids playing ball.

I haven't a clue who won, but it seems to me that's the moment I remember seeing this tall kid with skinny legs, the kid my friends said was the new Reformed church preacher's son. Somehow it seemed unfair. First Reformed calls a new guy and some great ball player, his kid, comes along like a free-bee.

Seems to me it had to be spring. If it was fall, we wouldn't have faced off on a diamond. If I'm right, then it didn't take long at all for that kid to become a friend because the town where we grew up, Oostburg, Wisconsin, had baseball teams I'd already been a part of for at least a year. Once our two schools shut their doors for summer, enemies became teammates, buddies.

And the two of us stayed friends for the next half-dozen years, very good buddies all through high school--football (he was the quarterback, I was a grunt), basketball (him underneath, me outside), track (he was a runner, those long legs started somewhere right beneath his ribs--I was a "weight man" in every sense), and, yes, baseball (first base, third base) because when the Christian school kids got together with the public school boys, we were good. We were very good. We won championships.

In high school, we both went over to the real enemy--Cedar Grove, another Dutch town--for girlfriends. But at OHS we took the same classes, lived in the same gym. We were good kids, the kind parents dream of. I don't remember fighting with my parents; I'm sure the preacher's kid got along with his just as well. High school halls are full of horror for millions; back then, we'd have called it a blast.

One of the most perplexing mysteries of my life with my friend Bob was why we both decided to go to college in Iowa, to Christian colleges 500 miles west but only a dozen miles apart. The only possible reason is tribalism, not Christian vs. public, but Christian vs. Christian. So deep was our devotion to our respective Dutch Reformed denominations that neither set of our God-fearing families even considered sending us--good, good friends, best friends--to the other's college, couldn't even think of it.

So off we went, and so ended, in a way, our friendship. For two years we met when the two colleges played basketball and baseball, but neither of us lasted long on the hardwood when the handwriting on the wall spelled out the end. I remember smiling, shaking hands, and then moving on.

In my life, Vietnam finally dominated. I didn't go (a weird heart, 4-F), and neither did he (287 in the draft lottery). I marched into a late Sixties rebel thing--long hair, bell bottoms, and anti-war activism--just about the time I quit basketball, discovered literature, and began dreaming about being right here with my fingers on the keys.

Bob stayed in the gym, coached at a couple of area high schools, then returned to the college where he'd graduated as a head bb coach when he was barely any older than the kids. And he was good. He was terrific. He was a great coach, which meant he went up in the coaching ranks until, a few years later, he walked away, not because he didn't like coaching but because he recognized in himself that his whole-hearted commitment made coaching hazardous to body, mind, and soul. He found his way into sports administration and loved it.

Now, in his retirement, he joined an adult writing class, where he followed the coach's game plan and created--and it wasn't always easy--his own story, so that, he told me, his great-grandkids would know who he was and, most specifically, what it was like for him to grow up. Hence, the title Things Were Different Then.

You can buy it on Amazon, but that's not what he's after. He just wanted to put it all down, his life--or as much of it as he remembers and wants to share--for his kids and theirs.

Strangely enough, real friendships seem not to require a lot of work. They can often go for years without having to be watered or weeded. Male friendships, some say, are especially hearty. They'll make it though anything. I think that's true of the two of us.

But then we do have our moments, like a couple of magical mystery tours back to Oostburg for high school reunions, a nine-hour drive that, the first time, became so rich with reminiscence that it locked us in the past, so much so that we went to Cedar Grove to drive past our old girlfriends' places even before we made it to Oostburg.

And then there was this. When my dad died, we had the visitation just before the funeral, all of it on a Saturday. And there he was, my friend Bob, on his way to Green Bay he said because one of his sons was playing for the Packers. All I knew--all I had to know--was that there he was in line to give me his sympathies, a hug.

I'm sure I was a little weepy when my dad died, but fifteen years later I don't remember crying at any particular time during that long weekend, but that one, when my old friend Bob walked up, tall and thin, in the reception line. That did me in.

It's precious--his book, I mean. To me, it's precious.

Thursday, March 26, 2020

Seven Deadlies--Pride

"In reality there is, perhaps no one of our natural passions so hard to subdue as pride. Disguise it, struggle with it, stifle it, mortify it as much as one pleases, it is still alive and will every now and then peep out and show itself; you will see it, perhaps, often in this history. For even if I could conceive that I had completely overcome it, I should probably be proud of my humility."Anyone who has ever read his autobiography, an all-American classic, can't help feel stunned to discover the man who penned the passage above is none other than our paunchy first ambassador to France, a most memorable member of the Constitutional Convention of 1787, a randy gentleman who, by his own confession, loved the ladies, not all of whom were, well, ladies.

That's right--it's none other than Ben Franklin writing about pride, if you can believe it--the man who virtually birthed the rags-to-riches saga, the man who came to Philly with nothing but a couple of hard rolls, and left this earth among this world's most esteemed. A man who wanted so badly to tell his own story that he created a genre and let everyone know. Ben Franklin on pride is something akin to Donald J. Trump on same--unlikely, impossible, even unimaginable. But there it is.

But there's this. That deft turn of phrase at the end is as much joke as it proverb, probably more. Even in confession, he loves to be cute.

The image up top is Pieter Bruegel's moralistic nightmare depiction of the very first of the Seven Deadlies, the sin of Pride. I'd like to be able to guide you through the mess, interpreting Bruegel's score of memorable images, but I'm not 16th century Flemish. Besides, here as elsewhere in his work, Bruegel sees and offers outlandish, even distasteful visions meant to leave you gasping. Maybe sometimes it's better you don't know.

Some need no interpretation at all. At the bottom center is a Bruegel monster perusing the beauty of his own underside as he sees it in a standup mirror reflecting what no one but he would like to see. There's a peacock, the animal icon of the sin of pride--that gorgeous tail on a bird only God could love. Beside the bird is Pride's central figure--all of Bruegel's Seven Deadlies have a central figure or embodiment. In the case of Pride, she's dressed for a ball of some type, dressed fashionably at least. Like the beast loving his buttocks, she's obsessed with her looks. There are mirrors in this phantasmagorical Pride, lots of them, as well there should be. The haughty are singularly obsessed.

And let me hazard a guess about the naked woman just to the left of Dame Pride, a woman surrounded by others. There has to be an Eve here somewhere. Bruegel could not have forgotten her or left her behind. No one knows his own religious associations, but the operating mythology of the world in which he lived are all Western and Christian. He knew Eve as well as he knew evil.

But to sit here and giggle at Pride seems its own kind of perversion, its own sin, its own selfishness. "Isn't this all just so cute?"

My mother would have to discover a Bible verse here to use the word, but I'm tempted to pull out of mothballs an old Dutch word that stayed in usage in the Schaap house even when the old language had been left behind two generations earlier. That word, as some know, is spotten, to make fun or sport of what should be sacred, to sing "Old Hundredth" with a clothespin on your nose.

Pride is heart of all sin. It is putting yourself first, wanting the knowledge only God can have or wield. Pride is the beginning of all sin and misdirection. Pride is what C. S. Lewis called "the anti-God."

And we all have it. Those who don't are only kidding themselves.

Which means I'm here somewhere. This cartoon nightmare of Bruegel's is a gas, isn't it? They all are. So much fun.

But somewhere in this horror I am too. Somewhere among the monsters, I have a place. Somewhere amid the misshapen, I am, ugly as sin. Here we are--Ben Franklin and me--hard as it is to admit--here we are, all of us, in dire need of forgiveness.

Amazing grace.

__________________

I started a little series on the Bruegel Seven Deadlies several years ago because I've always loved his startling work. I found the others lately, going through all the old posts, and I remembered that I'd done six but never finished. The only one I missed was the most deadly of all--Pride. Here it is. Now I've got them all.

Wednesday, March 25, 2020

Spanish Flu--a difficult look back

Or so said the editor of the Maurice Times, Maurice, Iowa, on Thursday, October 17, 1918. The worst was yet to come. He had no idea. My guess is that, in just a couple of days, he would have liked to take that lousy lynching reference out and burn it. People died in October, 1918, lots and lots of them. No one pushed them to flatten the curve.

Of course, the world was a different place. Maurice had a daily newspaper; today it hasn't much of a downtown. Many more people lived "on the land" back then, and they did so on small family farms, the pride of America, the exemplar of a faith that those who stayed close to the land were somehow blessedly pure of heart and mind. Food cost more back then--generally one-third of a family's income, twice as much as today. Nine out of ten babies were born at home; ten percent of all infants never made it to a year. Generally, we walked or rode horses.

In comparison to today, we had very limited scientific knowledge, and we were at war, the Great War. War, in fact, was greatly responsible for what came to be called Spanish Flu. It's origins are still being debated, but one of its sources was Fort Riley, Kansas, where 100 doughboys caught the new strain of influenza in one week. That number quadrupled the next. That was March of 1918.

Army camps--and there were 32 of them--were breeding grounds for a contagion that no one saw coming and ended with a death toll that seems unimaginable--50 million deaths worldwide. Here, in the U. S., 675,000 died out of a population of 100 million, as if all of Nebraska and South Dakota, today, were to be wiped out, in the U.S. over two million of us, gone.

When it comes to the stats from the Spanish Flu of 1918, it's hard not to read 'em and weep. And it came--this isn't nice to hear--in waves. The first, that spring, was virulent and contagious like nothing anyone had seen; but it didn't kill, at least not in the volume the second wave did. Spanish Flu got in the way of the war, then, in summer, drifted away until fall, when it returned with a vengeance, spread around by troop movements. Whatever mutation had occurred that summer made that new edition an unforgiving killer.

In three months, September through November, 1918, the rate of death simply took off. In October alone--remember, this was a second wave--almost 200,000 of us died.

Just one of them was Johanna Brinks Van Roekel, who was 26 years old and pregnant with the couple's first child. She and her husband, Otto, had been married at First Reformed Church, Orange City in January of 1915. There she is. Just one.

Just one of them was Johanna Brinks Van Roekel, who was 26 years old and pregnant with the couple's first child. She and her husband, Otto, had been married at First Reformed Church, Orange City in January of 1915. There she is. Just one.There are some parallels. There was lots of fake news. War-time censorship barred any reports of sicknesses and death in the training camps and on the battlefield; in England and France and America, journalists were not permitted to write about sickness, about flu, about contagion. The only newspapers who did stories were from Spain. Hence, even though Spain was no seed bed, the world came to know the truth through Spanish journalists.

Business interests kept quarantines down in large part because war machinery was so absolutely essential to war effort. Keeping that war's Rosy the Riveter from her job at the munitions factory meant undercutting our boys overseas. You can't tell people they can't come to work if what they're making is keeping U.S. troops alive. A century ago, balancing needs was far, far more difficult.

In one twelve-hour period at Camp Dodge in Des Moines, 1000 new cases of the Spanish influenza occured--that was October 8. When finally the curve flattened at Camp Dodge, 10 thousand soldiers were hospitalized, 700 died.

The Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918 didn't officially end until 1920. Its devastation was greatly enhanced by the Great War, millions of troops moving all over the world. Twenty million military and civilian people died in the "war to end all wars." Some say 50 million, world-wide, died of the flu.

We live in a different age. We know more than our ancestors did a century ago. We're staying away from each other now, not going out, and we've ended anything that draws more than a few of us together. We're all self-quarantined.

And, finally, remember this too: the Spanish flu ended. It quit, its powers gone. While no one has ever found a cure, we have successful inoculations.

It's easy to despair when you make the comparison. We're not the same. The coronavirus is not the Spanish Flu.

Some may choose not to read the story, not to make the comparison. But they do at their peril--and ours.

Tuesday, March 24, 2020

Morning Thanks--Comayagua church bells

You read that right--1636. Today, the Church of Mercy may well be the most significant colonial monument in Comayagua, Honduras, the country's very first capitol.

Its ancient clock--a Moor clock--still rings out the time every fifteen minutes, as it has since 1636. Get this--back then the clock was already 500 years old. Comayagua got it as a gift from Phillip II of Spain, when Honduras was a Spanish colony. It's old age, people say, is written on its face: the four is IIII, not IV, which, I'm told, is a much more modern form of Roman numeral.

Pigeons love the place, but then so do tourists because for a buck, if you're skinny enough, you can climb the well-worn cement steps all the way to the top of the belfry and not only look out on the city and the Honduran countryside, but also see, up close and personal, the assembly that keeps time in Comayagua, a mechanism created by Moors in the 12th century. Like I said, that clock was 500 years old when Phillip II gave it to the city in 1636.

What that old clock trips, of course, is the bells, none of which were built yesterday either, as is obvious, up close and personal.

It's impossible, really, to imagine yourself in a time and place so far removed from this distance, from the small town on the edge of the American Great Plains where we live, almost 400 years later, or, even more of a stretch, eight long centuries before some able Islamic workmen set together the mechanism of a clock that, even today, still sends out timely beauty to an old city Honduran city.

But I couldn't help thinking about the tower and the church and that old town when reading Olivia Hawker's The Ragged Edge of Night, a novel set in rural Germany in 1943 among men and women who have come to believe that what der Fuhrer is doing is in every possible way despicable, in their words, sin.

Anton Starzman is an ex-friar plagued by guilt that has accrued from what he didn't do to protect children once in his care. Anton meets a local priest, who operates in the German resistance. When the two of them take their first treacherous steps toward opening up, Father Emil tells Anton of the level of doubt, not faith, a man of the cloth can have--and he has. He tells the story of his own failure.

"Emil," Anton says, "how can you continue to lead a congregation?"

Father Emil points at the bells in the church he serves. Just then, just as every fifteen minutes, the bells ring out. “They’re beautiful, aren’t they?” Father Emil says. “The bells. They’ve hung in that tower for hundreds of years; imagine the things they have seen, the worlds they have known. When my thoughts are at their darkest, I listen to the bells and I remember that Germany hasn’t always been what it is now. Those bells remember it—the way we were before.” Father Emil is fully capable of irony. “I know I sound like a fool," he says, "—perhaps I am one. They are only bells, yet I can’t help but think of them as something more. . .Every time I hear them, I hear the past singing, too. I can’t help but remember all the people who came before."

But Anton reminds Father Emil of what it was that raised that inescapable doubt in his soul.

But Father Emil says he's learned to live it. “I took each day as it came. I still do—what else can any man do? I can’t worry about what might happen in the future; I can only tend to my small flock here and now, today, hour by hour, and pray that what I do is what God wills. . .Trust that everything is in God’s hands.”

The Honduran gentleman at far right is our Cathedral guide, the man who took our dollars. The woman beside him is Barbara, who loved all that ancient mechanism. I took the picture, making sure to get that can of WD-40 down in the corner, a kind of joke really.

The truth is, I liked the place--being up there, the ancient clock and bells, the can of WD-40 and the cardboard stuck in the corner to keep the pigeons from nesting; but not until I was back home again, not until I read a passage in a novel did the upper-room museum come alive.

So this morning I'm thankful for having squeezed my ample body up that skinny staircase to see all the history gathered above the city, I'm even more thankful for seeing it today in light of the confession of a Catholic priest in rural Germany in a novel set in the darkness of the Third Reich, a man who trusts in God by way of old church bells in what otherwise would be silent agony all around.

It was a priest in a novel that made the place come alive.

Monday, March 23, 2020

Morning Thanks--Grandpa's sermon

|

| The Rev. John C. and Gertrude Hemkes Schaap |

Some time ago, I unearthed an old cassette tape, on it a sermon my grandfather preached in December of 1951, Oostburg, Wisconsin, the town where I was born and reared. Years ago, my uncle gave it to me, a man who himself has been gone for decades.

That sermon was delivered in my home town, in the church where I spent my first seven years or so; I knew it when, halfway through, a train went by on the tracks just a few hundred yards west of where that church once stood. It was an evening service.

I plugged it into an old Walkman when I took a walk. It was terribly cold out, but I walked three miles, warmed by an ancient sermon that sounded almost exactly like I would have guessed it would have. I never heard my grandfather preach, at least not that I remember. He baptized me—that much I know. I was just six years old when he died.

But the moment I heard his voice, I recognized it--honestly, somehow I knew. I have no clue where the reservoir of memories is in the brain or how wide and encompassing it is, nor what specific function stands guard to let exactly which specific memories in or out, for that matter. But the pitch and timber of my grandpa's voice was there somehow, even though I thought I had no memory. Very strange. Almost eerie.

After I listened, I decided that Grandpa was no stemwinder, no Billy Graham, no "pulpiteer," as some might say. That night in old Oostburg, he didn't light the place up. Still, I don’t think I could

have enjoyed that hour more than I did, listening to an old man hold forth in a

voice I somehow recognized, in some ways, to be something of my very own.

And for that I’m thankful.

And for that I’m thankful.

Sunday, March 22, 2020

Reading Mother Teresa--Knowing God's Will

Do not conform to the pattern of this world,

but be transformed by the renewing of your mind.

Then you will be able to test and approve what God’s will is

– his good, pleasing and perfect will. Romans 12:2

Probably the most famous line in all of theater belongs to Prince Hamlet: “To be or not to be.” Won’t be long and I’ll be going through Hamlet again, and it’ll be my job, for the last time, to try to explain why that ubiquitous question of his is somehow timeless, arising formidably in all our lives, as it does, with sometimes alarming frequency, although the context is always different, thank goodness, few of us struggling with suicide or revenge for a murdered father.

Really difficult decisions about what to do are made more trying, or so it seems, by a transcendent, even eternal dimension to our decision-making, something we call “God’s will.” Joel Nederhood, in his book of devotions, The Forever People, claims that what Jesus himself gives us in the single petition of the Lord’s Prayer is the wish that we human beings would become more like the angels, simply taking God’s orders without question. “The reference to heaven in the perfect prayer,” he says (“Your will be done on earth as it is in heaven”), “reminds us that there is a realm where the will of God is absolutely supreme.” Therefore, he says, “Those who want to live eternal life beginning now realize that God’s will must be supreme,” a realization and commitment that should make Hamlet’s indecision silly, if not, dare I say it? – sinful.

Emphasis on should. If only complete submission to the will of God were that simple. In my life at least, determining God’s will has never been a piece of cake. Am I alone here?

Mother Teresa, on the other hand, had no such problem. When, occasionally, she was accused of acting without thinking, she excused herself on the basis of her commitment, her vow, to do God’s will always. Always.

She had to have been blessed with a mind cleansed of filtering agents, nor could she have a dime’s worth of cynicism. She never heard that still small voice that says, so frequently (at least to me and Hamlet), “well, hold on just a minute here.”

I once wrote an article about a retired missionary who lit up my day with jubilant recitations of the abundantly good life on the mission field. I came away from that interview truly blessed. The woman breathed joy.

Sometime later, another old missionary told me that the woman who’d blessed me with her stories had been indefatigable on the mission field, but her overflowing energy sometimes got her into trouble. If she was scheduled for a meeting, she’d forget in a heartbeat if, on the way, she spotted some children playing under a tree. She felt compelled to tell them about Jesus. Meetings be hanged.

She knew God’s will.

I couldn’t help think of her when I read that Mother Teresa “developed the habit of responding immediately to the demands of the present moment,” something she did so regularly that “this swiftness to act was misinterpreted and taken for impetuousness or lack of prudence” (34). Maybe that caliber of commitment is packaged with any call to mission work – you simply and wholeheartedly equate your mission with God’s will. End of subject.

As for me and my house, we’re more Hamlet-like, forever between a rock and hard place. I probably think too much; and, right now, smarting under Nederhood’s admonition, I’ll probably not repeat that petition from the Lord’s prayer again without seeing my own ink-faced sin in the mirror – “thy will be done.” Sounds so stinkin’ easy. Just like that – no brooding, no worrying, no sleepless nights. Just do it.

One of the few theological words with earthy Anglo-Saxon roots is atonement, which means, as it says, to be “at one” with God. I know two now-deceased women, missionaries both, who obviously got closer than I am to being at one with God.

But my cynical mind says so did David Koresh and Harold Camping and a thousand other cultists who thought they were abundantly “at one,” but were not.

There I go questioning again. I’m hopeless.

May God have mercy on me. And Hamlet.

Friday, March 20, 2020

Outbreak

Few among us are as totally untouched by the virus than we are. We live well apart from the madding crowd, out here with nothing behind us but flood plain. We're stocked and ready, and the house is warm, even after last night's blasted March blizzard. In a while, I'll crawl back into a warm bed and attempt the impossible--to wake my wife, who is and has always been a world-class sleeper, my toughest job on March 20, 2020.

There's nowhere we have to go. Both of us get along fairly well with solitude; this isn't Walden and we're not recluses, but being alone isn't chilling to either of us. We've got wi-fi and Netflix and enough toys to stay connected.

Not so with our kids. Our oldest has to go to the office, and when she does she leaves three kids at home, the oldest a college student on her own right now, dorms having been shut down. She and her brothers get assignments on-line, but when our daughter goes off to work she has a right to worry about whether all that work gets done without supervision. I can't imagine kids can go home-school over night and by themselves.

At the office, when the crew has coffee, they sit, as prescribed, six feet apart. Lots of businesses have closed. Restaurants serve up warm meals in microwavable containers and deliver them from drive-up windows. Sunday-go-to-meetin' means tuning in on sofas already overused. She worries. I can't imagine that she's any more anxious than gadzillions others here and around the world. But she's my daughter, and there's a certain tone of voice that's anxious because right now she's not at home with "at home."

Our son the fireman is anxious too. His beloved wife is a few weeks from the much-anticipated delivery of another daughter, a sister to their two-year-old beauty queen. COVID-19, he knows, could make the hospital a great deal less comforting than it is or certainly was, two weeks ago. His department has altered protocol, and he's enough of a news freak to know the dire predictions a dozen governors have asserted. Life just isn't the same at home or at the station, and it's scary--and the parent in me can hear it in his voice, in their voices.

There isn't much we can do about that, the two of us here on our island in the storm. For us to help our daughter at their place is simply not advisable. Maybe that'll change.

Maybe two weeks from now, we'll view the whole vista of present and future through new glasses. Maybe something will happen, something big. China's curve has flattened. So has South Korea's.

What's clear right now is that as of this morning no masked man on a white horse is coming over the hill to make the world a better place. The best we can do is stay in touch with each other and the One who has always promised deliverance.

I don't know that I could tell them as much right now or if they could hear it from a father whose burdens are far less weightier than theirs, but what I'd like to say is not just "fear not," as biblical as that line is. It's humanly impossible not to be anxious.

I don't have a cigar like Churchill, but what I'd like to say and what I believe is that, the Lord willing, this whole mad mess just could be our finest hour. Really.

Let us know if there's anything we can do, and promise us you'll remember this: you are loved.

Thursday, March 19, 2020

Morning Thanks--an expectant mom

In some ancient cultures, I once read, soon-to-be fathers lie

down beside their spouses and howl as their wives give birth, thereby taking

upon themselves some mysterious dose of their lover's pain and travail.

I don't know

that's true--it's just what I read.

I did no moaning myself. At the birth of our two children, to

call myself involved would be a stretch. Even

though we'd done all the Lamaze exercises--pillows and breathing and timing and

soothsaying--when the moment finally came and I stood there beside her, I think I held her hand in mine but I certainly didn't feel like a participant, more like a criminal.

An old friend--female!--once said in my presence that if men would really

like to know what childbirth is like, it's not all that difficult: just take

your upper lip, she said, and pull it back over your forehead. That's all I

need to know.

Some warm and wonderful couples manage to share the

pain and joy, the pangs of childbirth, and do so triumphantly, dutiful hubby

recording every last glorious moment on his phone.

Some beloved husbands are teammates, guides, honey-throated sweet-talkers; but

when my wife had our two children, any perception of the two of us being one

flesh was just so much hooey. I was useless, like some say, as teats on a bull.

Very soon, God willing, I'll be a grandfather again. It's a little girl,

and we pray she's got all her fingers and toes. I won't be sitting on pins and

needles as I was that day in Phoenix when my daughter, our first born, decided to leave the stronghold, nor will I be

as anxious as I was when my daughter's first--our first grandchild--made her

worrisome debut in Bellingham, Washington. Right now I'm still, well,

expectant, I guess I might say--expectant and worried--after all, there's this complicating matter of a novel virus.

So this morning's thanks is for my daughter-in-law, whose last few

weeks haven't been any more sweet than those unending early nauseous ones. She's about to do something half the world knows absolutely nothing of,

something profoundly primary and vastly beyond my imagination, something that

literally will change all our lives forever--she'll have a baby- they will--she

and her husband, our son. He'll be there too, probably just as much a spectator

as I ever was--and just as humbled.

This morning, I'm thankful for our daughter-in-law. And worried. And

anxious. And expectant.

What a great word--we're all prayerfully expectant.

Wednesday, March 18, 2020

Morning Thanks--and blessings

A few meetings scratched. No toilet paper--we're loaded anyway if you need a roll. No hamburger, but we buy quarters. On Monday, Fareway was out of eggs, but Barb says we're stocked. Sunday, like a million others, we did church from the couch. Went fine.

The gym is closed. That's a bummer.

I'm sentenced to hours and hours at the keyboard, but two MAJOR projects would have me here anyway, even if a certain blooming suction-cupped virus weren't roaring about like a lunatic Sherman tank. We don't live in a major urban area, so the elbow room country life affords makes social distancing a breeze.

Retired folks like us are in the cross hairs, I'm told, but, right now at least, our time and place leaves us pretty much untouched. I miss the gym. Badly. But to be honest, I can't think of another way in which I'm inconvenienced, as long as we don't somehow catch the dang bug.

The fact is, this morning I'm right where I normally am, in the basement. The cat is out so the house is still. There's nothing beyond the big windows to my right but darkness and pinprick farm lights. There's barely any traffic on Hwy. 60. Trains pass unnoticed. If we wouldn't watch the news, it would be hard to imagine we're under siege.

But we are. All of us.

We live, cheek by jowl, beside two colleges where life is a wild scramble. Yesterday, a Facebook friend/prof said after two hours of home schooling that she had determined the whole quarantined arrangement was not going to be sustainable. I wish I could help.

My grandson, with a furrowed brow, told his mother he was worried about us because he heard the elderly were in big trouble.

Really, Ian, so far, so good. These elderly, at least, are just fine. Don't know that I'm ready for two long months, but we're blessed.

This morning I'm thankful for Dr. Fauci, and thousands of others who carry the burden of getting the rest of us out there beyond the curve, the doctors and scientists who dare to tell us what we need to hear and see and do, experts who explain how we can arrive safely once again at nothing more or less than ordinary life. Oh, yes, and nurses--my word, nurses--who every hour of every day smile at those of us who aren't safe-and-sound.

Blessings for the journey.

Tuesday, March 17, 2020

Unimaginable Italy

A year and a half later, I'm left with two lasting memories of our trip to Italy--first, the endless parade of astonishing museums and art. To witness what we and so many others have did in the cradle of Western art and literature is far more wonderful than anyone can describe--or show, for that matter. You've got to be there.

I could go on endlessly.

But the memory that comes in, in a not-close second is immense crowds. People were everywhere--like us, tourists bobbing cameras on their chests, their phones up and about catching a gadzillion images every hour.

Oops. That one shouldn't have been there.

We went to Italy in September to avoid crowds. I don't want to think about what it must be like to be there in July or August. When you put your billfold away, you had to be sure that you weren't in another guy's pocket.

Let me foul the air a bit. Thinking about Rome or Venice without crowds is unimaginable, as unimaginable as Wall Drug at the Rapture (assuming a kind of universalism most post-mills wouldn't buy). I happened by not long ago, the Lone Tourist.

It's flat-out impossible to imagine St. Mark's immense piazza without a throng. Impossible.

because of respiratory droplets carrying minuscule pathogens so minute they can't even be photographed.

Humbling. All of it, immensely humbling.

Monday, March 16, 2020

Doomsday

MONDAY, MARCH 09, 2009

Look at the date--I left it on. I am going through old blog posts, found this one I wrote eleven years ago. Scary. That we're stressed right now goes without saying, but it's always a good idea to be wary of well-meaning end-timers.

Like Ezekiel, I guess, the man saw a vision and now has to tell others. What he saw ain't pretty--cities in flames, all manner of looting and licentiousness, a Mad Max world of mayhem that utterly horrified him, kept him sleepless, a world so rich in grotesque detail that he just had to tell the world. So he blogged. "An earth-shattering calamity is about to happen," he wrote. "It is going to be so frightening, we are all going to tremble – even the godliest among us."

_______________________

Like Ezekiel, I guess, the man saw a vision and now has to tell others. What he saw ain't pretty--cities in flames, all manner of looting and licentiousness, a Mad Max world of mayhem that utterly horrified him, kept him sleepless, a world so rich in grotesque detail that he just had to tell the world. So he blogged. "An earth-shattering calamity is about to happen," he wrote. "It is going to be so frightening, we are all going to tremble – even the godliest among us."

The prophet is no garden-variety madman. This is David Wilkerson, author of The Cross and Switchblade, a former highly successful youth minister in New York City. He's not just some Repent!-the-end-of-the-world-is-at-hand nut case naked beneath a sandwich board. Just look at his perfect hair.

That's why his apocalyptic vision made Matt Drudge take note this morning, and hence this blog's attention. Already the doom is echoing around the world millions of times.

And he may be right.

"It will engulf the whole megaplex, including areas of New Jersey and Connecticut. Major cities all across America will experience riots and blazing fires – such as we saw in Watts, Los Angeles, years ago," he explains. "There will be riots and fires in cities worldwide. There will be looting – including Times Square, New York City. What we are experiencing now is not a recession, not even a depression. We are under God’s wrath. In Psalm 11 it is written, "If the foundations are destroyed, what can the righteous do?"

He may be right. Thank goodness I live in Sioux County, Iowa, where, good moral thinking has it that the foundations have not yet been destroyed. But then, if he'd tune in to Google Earth, maybe he'd see fires way out here too--I don't know.

He may be right.

But if he's wrong, a year or two from now, will Drudge remember? will anyone?

Maybe I'm just jealous because I don't hear from the Lord in streaming video.

Don't touch that dial.

That having been said, this morning--cool and overcast, a mossy fog uncharacteristic of the region this time of year is hanging in the branches of the lindens. This morning for the very first time since last fall, a chorus of robins is piping through the trees. They're back. Couldn't see a one of them, but I heard, in the semi-darkness, yet another prophetic voice, a voice I truly believe.

______________________

Found this just this morning. Listen in to a couple minutes.

Wilkerson is talking to the Rev. Jimmy Bakker, who spent time in the pen for fraud. Wilkerson died in 2011. Bakker, by the way, out of prison and back in a TV ministry, was recently sued by the state of Missouri, where he lives, for "misrepresentations about the effectiveness of 'Silver Solution' as a treatment for 2019 novel coronavirus."

I'm not making this up.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)