Morning Thanks

Garrison Keillor once said we'd all be better off if we all started the day by giving thanks for just one thing. I'll try.

Friday, March 15, 2019

The Whiz--a story (i)

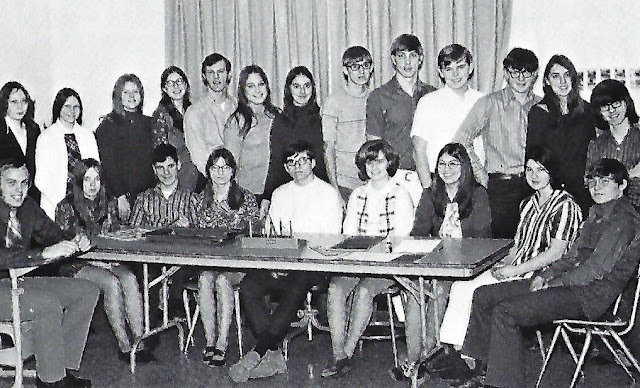

For the week, a story, this one drawn from a my teaching days (that's me--far, far left, in the tie). The story fiction, but the story line shadows an experience I remember well, not because I was ever a part of it, but because what happened between a student and a teacher happened just an hour before that whole class of kids showed up in my classroom. That hour I've not forgotten. It's a kind of "Me-Too" story that took place almost 50 years ago.

_____________________________

Poor Jessica. Her sun-streaked auburn hair was wonderfully wavy, but ironed flatness was still all the rage back then. She had dark, clear skin, but her glasses rather unpleasantly magnified her otherwise beautiful brown eyes and became a symbol of her isolation from the other kids: she loved to read, which, back then, just as today, is something of a social handicap in high school. A beautician might have trimmed her eyebrows, but I thought that heavy line drew maturity into her face.

To students, she was bookish and slightly overweight. To most faculty, including me, she was beautiful.

Poor Jessica. She came to me after school to get out of an essay: "React to Sir Francis Bacon's 'On Marriage and Single Life.'" It's odd to think that I ever assigned something like that, but that was years ago.

She couldn't do the assignment, she said, not with the math contest staring her down. Poor Jessica. Valedictorian. Stage manager for my first play. Editor of the newspaper. Did everything in high school except play basketball.

"That's okay," I told her. "Hand it in when you get time. Get yourself ready for math."

"I hate math," she said right away.

"You do not," I told her.

"I do too," she snapped.

"You're our only hope," I said. "Walters says--"

"I don't want to be the 'only hope,''' she said. "Who wants to be somebody's 'only hope,' Mr. Soerens?" She turned her face into a sickly smile.

"Okay then," I said, "don’t go."

"Sure," she said, "and do you realize what people would say?"

I was working on a mimeo master, scratching in the last few feathers on the portrait of the Indian warrior we used on the newspaper's masthead. I never even looked up as I remember. "Since when do you care what people think, Jess?" I said.

"Well thanks," she said.

''I'm pulling your leg," I told her. "Can't you tell when I'm kidding? Get it in when you can—now go fiddle with a slide rule or something."

I was single, four years older than she was; it was my first year teaching, and a young mature woman like Jessica, even though I don't think I understood it then, made me nervous.

She picked up a piece of chalk from the blackboard gutter and drew a cartoon tree on the board. "You don't want to talk to me," she said.

That's when I looked up. Her line was purely junior high, not typically Jessica, a senior, the smartest kid in school.

"What's the deal?” I said.

"I love math," she said suddenly, "I do." She shrugged her shoulders. "You think I'm crazy, don't you? You said in class that you always hated it and you didn't understand how people-"

"Jess," I said, "I don't think you're crazy for liking math." I picked up the master I was working on and held it up to the light to check my work. "Hey, listen--how about I put a goatee on the warrior?" It wasn't time for a joke.

“’On Marriage and Single Life,’” she said, "--right? That's the assignment? Well, here's my essay, ‘I'm getting married.’ That's my essay. You always say that we should make a commitment to what we write. I'm getting married.”

"Do I know the guy?" I said.

"You never met him."

It was unlike her to come to talk to me. She was nervous--agitated, clearly, and I was young. I thought immediately that she was telling me she was pregnant. And it all made sense. In a moment, I had written the entire story: smart girl, lonely, no dates, not bad looking. She picks up some farm kid, maybe an older guy looking for someone to come live out on that acreage his old man wants to buy. She fools around because she's curious, and besides, she wants to be loved more than anything.

In a minute I had it all figured out, so I spit it out, half in jest, allowing her the convenience to respond in whatever voice she wanted.

"You're pregnant," I said.

"I wish! Miss Goody Two-shoes?" she mocked.

I swung my chair around and stuck the tool away. "Jess," I said, "have you got something you want to tell me, or what?"

I think most students, male or female, would have just spit it out after standing there that long, but Jessica had brains enough to fight off her emotions.

"Can we go outside or something?" she said.

_____________________

Tomorrow: the story slowly emerges.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment