Morning Thanks

Friday, May 31, 2024

The Chronicles of Trump--chapter 45,786*

Wednesday, May 29, 2024

Monday, May 27, 2024

A story for Memorial Day

In the spring of 1942 he'd gone into flight school after graduation from a small Iowa college, spent a year in series of special schools, then took orders to Norfolk for duty in the North Atlantic. During his years keeping Nazi U-boats away from Allied shipping lanes, his unit of fighter pilots knocked off nine subs. "They didn't give you credit unless there was a heckuva oil stain on the water," he told me, a bowl of soup set on a couple of towels draped over his lap--lime chicken from his daughter in North Carolina. He says they know how to cook in North Carolina.

He should know. He married a North Carolina girl himself.

He's 94 years old, and everything you say has to be heavily amplified. We took a bad turn when we determined ear horns were ridiculous. All afternoon I could have used one, which is to say he could have. Honestly, I didn't say much at all for two hours while he told me about his life, but when I left I was pooped just from yelling the very few questions I did.

But what a joy it was to hear a story he probably doesn't tell all that often anymore, if in fact he ever did.

What brewed the tears was his remembering how that carrier sailed into the harbor and how right there on the pier in front of him coming closer and closer and closer was his brand new wife standing among the others gathered there. That happened 72 years ago. Just seeing her there in his memory still brought tears.

When the Nazis began to recharge their batteries at night on the North Atlantic, he and his fighter plane buddies had to learn whole new technologies for going after subs in the dark. Where there was once a bomb in the hold, the Navy now installed a flood light. To learn the new flying tricks, the whole bunch of them were sent to Florida. He told his sweetheart to take a train down with the other women. "But, honey," she told him, "we're not married."

"Then that'll have to change," he told her.

The next time that carrier and its nine planes and crews turned away from combat on the high seas and returned to port for resupply was the time he spotted her on the pier waiting for him--that's the moment he'll never forget. He's 94, and he doesn't walk well, but the memory of seeing her waiting on the pier brought tears from someplace so deep inside we all probably wish we held such a treasure.

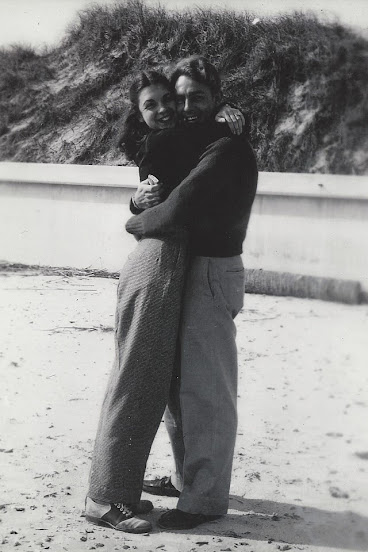

That's them in the picture. He'd met her at a dance in Norfolk, asked her to dance three times in a row, then asked her if next time he was in port he could date her. She said yes. He wrote her address on his sharp white cuff.

Look at that picture. It's just about the most beautiful thing, isn't it?

But he broke just enough for me to see an edge of tears in his eyes one other time too when he told me about his life. Land prices skyrocketed in 70s and early 80s; and when they did, farmers loaded up on everything--on land, on machinery, on cattle. As long as their paper worth was out of sight, so was reason.

But the market didn't hold, and when land prices fell off the table the whole works buckled like a house of cards. Good people, hard-working people, people who prayed to the Almighty, suddenly found themselves so far gone in debt there was no way out except to somehow cut losses and dreams.

"That was a bad time, wasn't it?" I asked him.

That's when he cried again.

He'd become a banker, a good one, a man of prayer. "The Board met everyday at six in the morning and we'd go over loans," he told me, his lips shivering in the overheated apartment.

Twice he cried this afternoon, this precious old man who, once upon a time in the inky dark over a cold ocean operated a joystick with a trigger that wasn't a game at all.

Twice he cried. I saw it. Once in joy and once in misery. All in life.

So go ahead and ask me about my day yesterday. I'll be happy to tell you.

It couldn't have been richer. I'm thankful for being there.

Sunday, May 26, 2024

Sunday Morning Meds--from Psalm 84

“Hear my prayer, O LORD God Almighty;

listen to me, O God of Jacob."

In Match Point, or

so it seems to me, Allen’s interests are metaphysical, as they often are. In

fact, the film is not so subtly crafted, prompting one to think the story is an

object lesson in grace—amazing grace, in fact, but perverse grace, certainly

not the species that prompted one-time slave-trader John Newton to write the famous

hymn.

Relatively ordinary potboiler, until the surprisingly metaphysical last few moments of the film. By sheer luck—a series of coincidences the murderer doesn’t even know himself Wilton gets away with his heinous crimes. As Allen makes visually (and somewhat painfully) clear throughout the film, fate is simply a matter of where the ball bounces. The trajectory of our lives has less to do with our designs than plain old luck.

All of which reminds me, in a way, of a famous Allen quote: “If it turns out that there is a God, I don't think that he's evil. The worst that you can say about him is that basically he's an underachiever.” Don’t look for moral order in the universe, Allen maintains, just deal the cards.

In an opening scene, Wilton is reading Crime and Punishment, a set up that’s irresistible, as if Allen is taking great delight in revising Dostoyevsky’s famous tale, taking the novel to task for its clear suggestion of the importance of faith and salvation.

And yet, perhaps, differences are merely a matter of degree. After all, it’s Dostoyevsky who once wrote, “It is not as a child that I believe and confess Jesus Christ. My hosanna is born of a furnace of doubt.”

Woody Allen has his own furnaces, I believe. Match Point is as memorable as it is because it takes on cosmic issues, the way Allen’s work always does. If we aren’t in charge, who is? Is anyone? Is there a God? If there is, is he an underachiever? Not many films ask such questions so openly; that he can’t untangle himself from the messy mysteries of existence suggests an eternal battle, here as elsewhere in his work.

Faith may well seem the opposite of doubt, but I doubt it. In Psalm 84, the seemingly boundless faith of the psalmist is undercut, even deconstructed by the command form he employs, the vehemence, the raised pointer of his begging. “Listen to me, God!” he says, suggesting that the Creator of heaven and earth hasn’t always kept his end of the bargain. There are almost equal portions of faith and doubt in the words of this verse, as much joy in the promise of God’s presence as there is stiff fear of his absence.

Isn’t it amazing that a single line can hold so much tension, so much humanity, so much of what we recognize ourselves to be?

So much of who we are.

Friday, May 24, 2024

Alice Munro 103

"If I had been making a proper story out of this,I would have ended it, I think, with my mother not answering and going ahead of me across the pasture."

So begins the last paragraph of this altogether Munro-ish story, "The Ottawa Valley," and if you stayed with the story all the way through, you might be a little resentful because she's telling us--last darn paragraph--what this trip to the Ottawa Valley was all about--it was about this unnamed woman who is a ton like Alice Munro, taking us along on a nostalgic trip into her mother's past in order to write a story? Are you kidding me?

Well, let's start here. To Munro, writing a story is a calling . Furthermore, she most certainly wants us to take to heart what her narrator is undertaking--it's a quest, on her part, for understanding, for understanding herself in fact, by understanding her mother. She believes that writing about her mother will further advance her own understanding of herself--and so do I, by the way.

She goes on thusly:

That would have done. I didn't stop there, I suppose, because I wanted to find out more, remember more. I wanted to bring back all I could. Now I look at what I have done and it is like a series of snapshots, like the brownish snapshots with fancy borders that my parents' old camera used to take. In these snapshots Aunt Dodie and Uncle James and even Aunt Lena, even her children, come out clear enough. (All these people dead now except the children; who have turned into decent friendly wage earners, not a criminal among them).

And that's what she's done in the story--given us pictures--postcards--little narratives that open up a image of her mother that her daughter hadn't before seen or examined.

Like the central comedy of "The Ottawa Valley," a darling little anecdote about Aunt Dodie and her mother pulling a fast one on Allen Durand (who has become a somebody in town) by, when they were just kids, sewing up his fly, then feeding him a half gallon of lemonade (he was in the mow during haying), then waiting from behind a wall with a knothole, until nature drew its course. Aunt Dodie thinks the whole revealing event an absolute hoot; the narrator's mother isn't quite so coarse, she giggles and claims she didn't look. Aunt Dodie tells her she laughed just as hard and looked just as long as her cousin did.

What has that whole long and delightful story have to do with "The Ottawa Valley," the story itself? For the narrator, who, at the end of the story tells us she's trying to understand her mother, the trip was a treasure because it offers her another view of her mother, not just the do-good sister or Aunt Dodie, a ball of fun, but also someone who had a past that included enjoying full frontal nudity of a man worth looking at. That "mom" has not been a mother she knew. And she is dying.

With what purpose," Alice Munro's narrator says in that surprising last paragraph. "With what purpose? To mark her off, to describe, to illumine, to celebrate, to get rid of her; and it did not work, for she looms too close, just as she always did."

To understand her mother--and her own relationship to her--is something that seems beyond the story-teller. She goes home with her, meets her sister whose shenanigans are nothing at all like her stoic mother, then comes back to a typewriter and confesses that all that new info, those new images she's collected haven't really helped her understand.

She is heavy as always, she weighs everything down, and yet--she is indistinct, her edges melt and flow. Which means she has stuck to me as close as ever and refused to all away and I would go on and on, applying what skills I have, u sing whatever I know, and it would always be the same.

It seems to me that what Alice Munro is saying here is she'll never pin her mother down as grade-schoolers pin down spiders and grasshoppers. She'll never understand her fully, which is to say, by extension, that she'll really never quite get the whole of humanity in one of the snapshots she takes--why? because her mom is too complex, which is to say, all human beings are.

As true as that may be, it's really worth the chase. She still writes the story, and we know more about "The Ottawa Valley."

Thursday, May 23, 2024

Commencement

|

| Grandson Ian, Class of '04 |

Yesterday, a new physical therapist introduced herself to me by saying that I didn't need any introduction because long, long ago I'd been her grade school graduation speaker. She even remembered some things. "You were saying something about nachos," she told me. I honestly can't imagine what that must have been, but she remembered. Not the moral lesson--just the nachos. No matter, I was honored. Sort of.

Truth is, I've been a graduation speaker at more events than I could list--maybe ten grade school grads (including my daughter's and my granddaughter's), three or four high schools (my poor daughter's), even a college commencement speaker. That's a lot of nachos. What I'm saying is, I know how tough a job it is or was. That the physical therapist remembered a line from her grade school grad speaker is a wonder because I don't remember a thing about any of them because, honestly, the evening belongs to the grads.

Last night it did. We attended our last grandson's grade school graduation at a huge church in Sioux Center, Iowa, and it was just plain grand. No speaker. None. No one specially chosen to deliver wisdom to the grads. Just them. It was wonderful.

First, videos--each of the 70 kids featured, then an intro from the "head of school," then prayer and a praise band (actual singable music). A few warm-hearted reminiscences from teachers ("How can we forget COVID!!" from Mrs. Vander Kooi, fourth grade), the long processional for diplomas, a marvelous duet from two teachers--and Casey's chocolate chip cookies afterwards.

The evening featured the students, put them out front, gave them the laurels, even by way of the evening's liturgy. No outside speaker, no valedictory, just bunches of students contributing. I couldn't help thinking that authority gave way to community. It was warm, personal, greatly student-centered, a sweet departure from the old way.

This proud grandpa says it was a grand evening.

Wednesday, May 22, 2024

The Unsung Heroes of the West

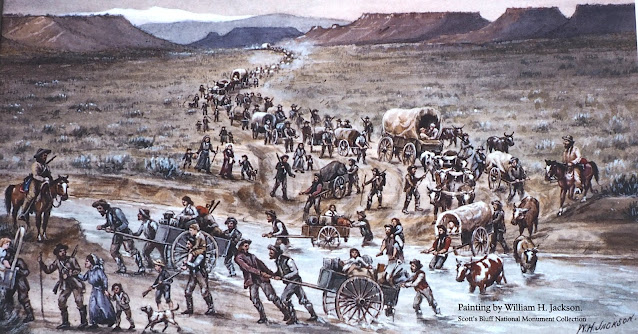

With the taste of gold in the air, thousands of men went wild-goose-ing for bright and shiny dreams. One freighter (a truck-driver, basically, long-distance wagon-eer) remembered working the Bozeman Trail back then, when it was broad as a four-lane highway. He wasn't panning or picking, just hauling freight, tons of it. It's 1854. Just loads of traffic.

Tuesday, May 21, 2024

Alice Munro 102

"Postcards," from her first collection of stories, Dance of the Happy Shades, is much lighter fare than "Friend of My Youth," but it's drawn from the same quarry. It's female, powerfully so, and features a beleaguered young woman who is trying to determine what it means to be a woman in the world of a small town named Jubilee, Ontario.

She's given herself away, never a particularly good idea, even if the odds are in your favor. She's made a habit of sleeping with a son of the town's meager aristocracy, and been promised, tacitly, that she will be the man's bride once his crochety old lady finally leaves the upstairs bedroom and the planet.

She has reason to doubt him--a reaction others of her friends and family share; but this man, Clare, is what Munro calls a "public man," perhaps of no greater significance than anyone else, but a man who comes from an echelon of small-town nobility that is somehow superior to others. In short his "public" character, a kindly disposition, makes people fall in love with him, including Helen, or at least treasure his company.

It's a fit that does her well, or so she reasons, sex for his promises, until Clare's promise crash and burn. He marries someone on a warm week in the cold winter, someone from Nebraska, someone he met in Florida, where he's been vacationing. The news hits poor Helen where it hurts . What she doesn't know (at one point she tells the reader she was anxious to hear what she was going to say to the man) is how to react, and in the single scene which dominates the story, she parks her car (a gift from him by the way) on the street just outside his home and lays on the horn time after time, yelling at Clare to get is butt out of his marital bed to talk to her.

She's been jilted, and every last soul old enough to understand knows very well that she has, which only increases her pain.

I'm not doing the story credit, but I'm assuming that few who read these words know or remember the story. The fact of the matter is the story is a hoot, and while we feel for poor Helen, the doggone story itself is hilarious. Poor Helen captures our sympathies, but mostly she's a cartoon.

So let's return, for a minute, to blasted thesis that got me into this: Alice Munro, who died at 92 years old last week, was the finest short story writer in Canada, in North America, and--who knows?--the world!

Why and how? Those questions made a teacher out of me again after so many years. "Postcards" is wonderfully entertaining, as her earliest stories tended to be. They require little reflection and introspection, and, like "Postcards" can be downright hilarious.

Which is not to say Munro doesn't have something serious to say, in this case, once again about being female in (at least) Jubilee, Ontario. Here's Helen's summary as she second-guesses her fate:

If I had really thought about what he was like, Clare MacQuarrie, if I had paid attention, I would have started out much differently with him and maybe felt differently too, though heaven knows that would have mattered, in the end.

So, all of this trauma, whose fault is it?

Hers. Maybe.

Than again, maybe not.

Is there a warning in this story for young women? Maybe. But that's not what Munro is about. She's not trying to change behavior, only to examine it--for its sadness and its humor--and hope we enjoy the examination.

___________________

If you would like to know Munro's work better, go to your library and ask for Select Stories (Vintage, 1996). You may have to get it on inter-library loan, but your friendly librarian will be glad to do that. I'll take the stories I talk about (maybe ten or so) from that collection. Next class, let's try "The Ottawa Valley."

Monday, May 20, 2024

Alice Munro 101

There's something elitist about that classification, but what I mean to say is her "literary-ness" means she wasn't, nor could she be, "popular." It is a measure of her abilities as a writer that while her stories make demands on readers, she was immensely popular anyway, largely because--as you can well imagine--the payoff finally was well worth the depth her stories reached. She is demanding, not always easy.

Always there is plot, but never is it linear--a + b = c. "In Friend of My Youth," three stories telescope. One is the narrator's--what she wants to do in writing this story; a second conflict/plot involves her mother's needs, never clearly defined; and the third, the one that demands most of our time as readers, a lifelong plot that seems only tangential to the narrator's story or her mother's, an almost gothic tale about a family committed to an old-time religion that keeps them entirely separate from the society around them. Three plots, three conflicts, three settings, three dilemmas, linked as the writer/narrator tries to measure them for meaning to her own life.

The story, like so many others, goes deep into motivations and decisions not always understandable nor planned. "Friend" is literary fiction.

Her characters are never fully knowable, even though they're fascinating. She loved mystery, but if there are any murder victims in her stories, I don't remember them. Often some mystery is involved in the deaths she records, but of greater interest to Alice Munro than the death themselves is the effects--long term, even generational--on descendants or neighbors or attending community.

What was of greatest joy to her was the ordinary mysteries of our lives. It's as if she wielded a darning needle and not a pen, not because everything in her stories seemed hand-woven, but also because that needle was ever capable of pulling apart nothing less than life itself.

When you finish the story, you don't simply turn the page--she wants you fully taken by what it might have been that made a trip to the five-and-dime as incredible as it somehow was to a woman who can't quite forget nor understands why.

The real matters of "Friend" are a broken engagement, an unwanted pregnancy, an early death, an unlikely second marriage. What weds those events is the gracious, committed joy of her mother's friend, severely wounded but never, seemingly, hurt, a woman held in place by her commitment to a faith whose parameters seem dolefully out-of-fashion--and are.

Munro's women--and most all of her protagonists were (no! are) women--are, often as not, trying their best to figure something out about identity, about who they are and why they are who they are.

Not all of us are engaged in the quest to know ourselves--not all, but most. And most of our pilgrimages into the our own histories take us into areas we can only vaguely ascertain. Alice Munro's "literary" fiction will read best if you tell yourself ahead of time that there are mysteries beyond our ken, even if and when we suffer them ourselves.

It's not knowing answers that ring true to life; it's determining, after passionate pursuit, that the pursuit itself is the human story. To Munro life is as mysterious as it is delightful, or, even better, delightful because it's mysterious.

Let's start there, or so saith this old teacher. Let's begin with the thesis that in Munro's world (often rural Ontario) no answers are cheap or forthcoming, and, isn't that a wonderful thing?

I used to dream abut my mother, and though the details in the dream varied, the surprise in it was always the same. The dream stopped, I suppose, because it was too transparent in its hopefulness, too easy in its forgiveness.

That's the first line of "Friend of My Youth." It could easily be the last. It's the whole blessed tale. It's where we end and where we began.

And in that circle is life itself.

That's where Alice Munro finds her stories--in the middle of what we are.

The old teacher in me is going to page through some of Alice Munro's greatest hits, even though I'm quite sure I'm not going to be talking to people who know the stories. If you would like to read along, go to your local library and pick up a copy of Munro's Selected Stories (1996). I'll pull them all from that collection.

Next time--"Postcard."

Sunday, May 19, 2024

Sunday Morning Meds--from Psalm 84

These Sunday Morning meditations were penned years ago, one after another, until I'd done 365, just for my own edification really. This one should really have a sequel because my teaching gig at the home turned into one of the highlights of my life. The joy is almost too great to pass along, but it turned the old folks home into "a place of springs." Their honesty and joy was a rich blessing.

These days, I'm almost one of the 'em.

"As they pass through the

The word got out. The good folks at Elim Home got the news of their being visited by a writer, who was going to read something he’d written, the man who’d written things so often in their church magazine. “You know him, maybe, eh? He’s from a long ways away—from Iowa, in the States—and he’s coming to Elim Home. Ja, sure.”

Lots of Dutch brogues in this place.

One of them phoned the man who arranged my schedule on this visit.

“’Ve was yust now talking,” he told him, “and ‘ve ‘vere ‘vondering whethder Mr. Schaap might yust come a little early ant’ help us learn to write our own stories.”

Some requests simply aren’t to be denied.

It ought to be a kick. I’m sure I’ll live through it and have plenty of laughs along the way.

I’m not sure why, but that polite request makes me smile. Maybe it’s because I just finished another couple of semesters of teaching. Sometimes—not all the time, and I don’t want to overstate—coming into class can be like walking into a wake. Not a student in the room is really interested in Ralph Waldo Emerson. But this Vancouver class, this gaggle of seniors, they want more time, not less, and more attention, not less. They want real teaching. They want to learn. I know, I know, I sound really whiny.

But the possibility of assuaging my wounded pride is not the only reason the Elim Home request has made my week. The other is what it is those old folks are demanding: they want help writing their stories. Good night, they’re all seniors, and they’re just now getting started thinking seriously about writing their life stories. “How can ‘ve do dat best?” they’ll say, I’m sure. There’s just something so good, so strong, so hearty about a home full of old folks wanting to learn. Whether they can is a good question; that they want to is unmitigated blessing.

It seems the older I get, the more I have to learn to pay attention to those kinds of blessings or I miss them altogether. Honestly, the prospect of visiting a couple dozen retired Dutch immigrants who want to write their life stories—it’s sheer joy to consider. It’s a peppermint in a snoozy sermon. It’s enough to make you smile.

I don’t know that anyone has a clue about the Valley of Baca, although I’d guess that some biblical scholars will be happy to hazard a theory. But then, I’m not sure that the relative glories of that place are all that important to understanding the psalm. What’s at the heart of these verses of Psalm 84 is a tribute to people who pay attention to joy, who let it fill them, who let it carry them over the dark places. These are people of pilgrimage, who take their strength from God, whose very footsteps make the desert bloom. These are people who sing in the rain.

And Thursday I’ll be blest by being among ‘em.

Friday, May 17, 2024

Old McDonald

It's in me too, even though as far back as I can reach there are no farmers--well, there were no farmers who knew and loved what they were doing. Doesn't matter really. In this country at least, there's enough of Jefferson in the national psyche to recognize that, this time of year, it's only right and fitting to plant seeds in the ground. It's simply what we do, like breathing. "People who don't plant seeds don't know God," an old friend used to quip, only half-jokingly.

So I shouldn't be surprised that our granddaughter has seemingly taken it up and done so so splendidly. "Do you think we could possibly use some space in your vegetable boxes--just some?" In this life, generally grandparents don't say no to such requests. What's a few tomatoes anyway? You know how it goes: by early October it's just work to anything with them. As much as you know how much you'll miss 'em come February, it's easier to let them go, then annoint a special Saturday to mopping up the shards left from the season.

"Sure," we said. "We're getting old. We don't need all that space."

And thus it began.

She has sisters-in-law who rekindle memories of Old McDonald. She'll have the world's best training in the world's best soil, and--guess what?--we'll have them around our place. They'll be here, in our house, in our backyard. We know people who move hundreds of miles to be anywhere close to their grandchildren. My word--ours will spend a goodly chunk of this summer in our backyard.

Besides, it's cute to watch them, busy as ground squirrels, measuring inches and plopping beans into furrows--and there are onion sets, some vegetably stuff I never heard of, even broccoli--they're not holding back for a couple of rookies.

Get this: we get to watch. How many grandparents aren't at this moment going seasonably green with envy?

And then there's this too. Sometime this fall, when mopping up will be the only thing going on out back, there'll be more, much more than there ever was because next fall sometime the two of them will be joined by one of their very own, a roly-poly miracle the two of them have nurtured into life, a brand new baby.

It's impossible to imagine that, but go ahead and try. We'll be great-grandparents, amazing as that may sound.

You can bet I won't let them out of mopping up. It's the duty of every last gardener on the planet. When the northwest winds set up for winter, flecked with snow, somebody's got to clean up.

"Dad's got most the work done," great-Grandma will say. "But come on by--just be sure you bring the family."

Thursday, May 16, 2024

New Heavens and a New Earth

Yesterday's note from Frederick Buechner created a scene I can't help but live with. I'm not sure of his or its sheer orthodoxy, or whoever's orthodoxy we're driven by these days; but his resolution of a view of the afterlife seems warmfully offered here, and I say, quite forcefully, that I like it.

It would be advantageous to have him offer a comment himself right now, having passed away some years ago. He's a far more trustworthy officer of the truth these days, I'd suppose, at least when it comes to what he's offering here.

|

Heaven |

|

|

|

|

|

“AND I SAW THE HOLY CITY, new Jerusalem, coming down out of

heaven from God, prepared as a bride adorned for her husband; and I heard a

great voice from the throne saying . . . 'Behold, I make all things new'

" (Revelation 21:2-5). Everything is gone that ever made Jerusalem, like all cities,

torn apart, dangerous, heartbreaking, seamy. You walk the streets in peace

now. Small children play unattended in the parks. No stranger goes by whom

you can't imagine a fast friend. The city has become what those who loved it

always dreamed and what in their dreams it always was. The new Jerusalem.

That seems to be the secret of heaven. The new Chicago, Leningrad, Hiroshima,

Baghdad. The new bus driver, hot-dog man, seamstress, hairdresser. The new

you, me, everybody. It was always buried there like treasure in all of us—the best

we had it in us to become—and there were times you could almost see it. Even

the least likely face, asleep, bore traces of it. Even the bombed-out city

after nightfall with the public squares in a shambles and moonlight silvering

the broken pavement. To speak of heavenly music or a heavenly day isn't

always to gush but sometimes to catch a glimpse of something. "Death

shall be no more, neither shall there be mourning nor crying nor pain any

more," the book of Revelation says (21:4). You can catch a glimpse of

that too in almost anybody's eyes if you choose the right moment to look,

even in animals' eyes. If the new is to be born, though, the old has to die. It is the

law of the place. For the best to happen, the worst must stop happening—the

worst we are, the worst we do. But maybe it isn't as difficult as it sounds.

It was a hardened criminal within minutes of death, after all, who said only,

"Jesus, remember me," and that turned out to be enough. "This

day you will be with me in paradise" was the answer he just managed to

hear. -Originally published in Whistling in the

Dark and later in Beyond Words

|

Wednesday, May 15, 2024

Alice Munro (1931-2024)

I didn't know I'd be drawn into Native American history. I didn't know we'd come to live in a brand new house with an entire acre of land between us and the Floyd River. I had no idea that acre and that land would employ us, spring 'till fall. I thought I'd pay golf just up the road and drown worms in nearby ponds, and the river, of course. The truth is I didn't know what retirement was or would be.

I'd created mandates, from what little I knew. I'd get myself a definitive edition of Emily Dickinson (accomplished!) and go through the poems (begun. . .) as closely as I could, knowing that often a meaning would be elusive. "Read Emily Dickinson."

I took along, from school, thirty or forty books from my teaching library, just a few books that I treasured--Jane Smiley's A Thousand Acres, every last Ray Carver I had, Toni Morrison's Beloved, a few more. I've never been a person who reads a book twice--I'm not that good of a reader. Honestly, I've been envious for most of my days of the instinctual love of reading some people have. I don't have it--I wish I did. There are books I took along simply because I didn't know if I could honestly live without them all around, but I've never read a book twice--that takes a real reader.

I took with us my entire collection of Alice Munro. Having read maybe three or four of them and used many individual stories in classes, I knew her work (she was only a short story writer) were perfectly wonderful. When I retire, I told myself, "I'm going to read the entire library of Alice Munro, eight or ten books of her short stories, because I loved so much of what I'd read.

See that picture above?--that's the first row of the upper bookcase standing in front of my desk. Haven't been touched until this morning, when I opened Friend of My Youth and was once again reminded how I learned to love reading, an act that, as I said, didn't come natural to me. I am--I'm baring my soul here--an analyzer, not simply a listener, and while there are advantages to what I do, there are disadvantages too. Just look at what happens to the bare page. Who do you know that scribbles up a page like that?

And now she's gone. For a long time, there has been no new Alice Munro collection--I would suppose that's part of it too. But the announcement seemed almost a missive from outer space--"Alice Munro--dead?"

Let me just say this quickly: she was (and is: "literature lives") nothing less than the best short story writer of all time.

I won't say anymore, but don't be surprised if you read more about her on these pages because I really ought to make it a solemn vow now, a resolution, to read all I have of Alice Munro.

There she is, still alive, right down front of the desk where I'm sitting now. See her? Top of the page.

Tuesday, May 14, 2024

Morning Thanks--the little climber

Including the climbers. We've got a wonderful stony retaining wall running on both sides of our backyard. I made it--just about the only thing about this place in the country that I constructed--not the rocks, of course; they took millions of years, but the wall itself--think Robert Frost maybe.

Several years ago, I bought a darling little climber from the plant store, not because I knew a thing about its identity, but because the idea of some climbing plant inching its way up the stone walls, a vine-like creation--sounded perfectly beautiful--no, let me change that, "looked" perfectly beautiful in the magic garden my imagination creates every April. Bought it--complete with its own little ladder to remind itself of what it is and why it does what it does--planted it (following directions) then waited for it to begin to fulfill the promises it had registered in my mind.

Let's just say whatever arose from the good Iowa soil was pitiful, not worth mentioning. The plant itself did make clear in packaging that it was a perennial, but it's first year's show was so meager that whether or not it cared to show its face the second spring, to me, completely was to me a decision it along would make. (Meanwhile, I bought a cheap little trellis, more for the birds than that little climber.

What happened? Nothing. Perfectly nothing. Meanwhile the bushes my wife had chosen were prospering with such abundance that whatever it was I'd planted, that little oh-so-cute climber, for instance, simply lost their standing, which is a nice way of saying, I suppose, that they lost their square corner of creation.

Last year, amazingly, that little climber inched up healthily, as if out of nowhere, but, once again lost its standing when the bushes beside it just shouldered it out of the way. By September, I thought it was gone until I started cleaning up and realized that what it had eventually spun out was quite considerable--but definitely overshadowed by the healthy perennial bushes all around.

And now's the time to look back at that picture at the top of the page because that's our unnamed climbing plant, purchased as many as a half-dozen years ago, but this spring off to the kind of start any major leaguer would be happy about, already climbing the old rickety trellis I stuck when I actually had dreams for what that climber could do or be.

Now rather than create the sermon out of all of this, I'll let you fellow Calvinists write your own, although in this case the sermon writes itself, and does so beautifully too, even if I can't name the climber, because this year the climber is going to establish a presence, a standing. Who knows how it'll flower?--or if it will at all. Who knows, I may just put my phone to work and find out who it is.

The climber deserves a name.

End of sermon.

Monday, May 13, 2024

I'm thinking, "Mothers' Day, hmmm. . ."

Seems downright amazing today, but in the years just following the Civil War, two activist groups determined to get women the right to vote, went toe-to-toe for reasons that, in retrospect, seem as lightweight as their skirmishing. The National Women’s Suffrage Association (NWSA) actually opposed the passing of the 15th amendment to the U. S. Constitution (prohibiting states from denying male citizens the right to vote, thus admitting African-American men). The NWSA was not the least bit racist. The grounds for their opposition was that admitting the newly-freed slaves to vote seemed wrong if women of all races weren’t given the same right.

On the other hand, the American Women’s Suffrage Association (AWSA) supported the passage of the 15th amendment, arguing that even if women did not gain enfranchisement at this particular time, excluding African-American men from gaining their freedom would perpetuate injustice and be, quite simply, flat-out wrong.

‘Twas a fierce rivalry, as political battles are, even though both organizations laid claim to the same mission—to gain a woman’s right to vote—in the land of the free and the home of the brave. The battle was waged about how.

We tend to think of change coming to rural areas like our own only when winds blow hard from either coast. In this case, however, it’s simply not true. When the two warring women’s groups pulled themselves back together, it was here, in Nebraska, in 1890, at the bidding of locals who had, for the most part, kept themselves above fracas.

Erasmus Correll, who edited the Hebron Journal, and his wife—together the two of them created the greatly successful Western Women’s Journal—were tireless voices for the women’s suffrage, writing extensively themselves but also bringing suffrage notables to the rural heartland, women like Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, who gave speeches to packed houses in small towns.

Mr. Correll was rewarded by the AWSA for his pioneering work by being chosen as its President in 1881. He was indefatigable. "It affords me much pleasure to thankfully accept the position and its duties,” he said, “and divide the honor among the earnest men and women who are. . .seeking the highest political welfare of humanity." Correll noted that "Having devoted my life to the cause of Equal Rights, no labor will be avoided.” Presumably, none was.

Just a year later the warring factions signed a peace accord to combine forces in the quest for women’s suffrage. Local folks played peacemakers and, at the same time, roused the newly conformed army for battle.

Hard as it is to believe, getting women the vote was almost impossible, even here, despite the activism. One of the most prominent advocates in Nebraska told his daughter in a private letter that the fight for women’s rights was no cakewalk. “Between ourselves--there is no more hope for carrying woman suffrage in Nebraska than of the millennium coming next year,” he told her. “. . .We don’t want to discourage the workers, . . .but don't publish my predictions.”

And it wouldn’t be a short war. Thirty-five years would have to pass before Nebraska passed women’s suffrage in 1917, Iowa and South Dakota in 1919, with the passage of the 19th amendment.

Great power in that crusade began here, not far away in rural America. Why? One reason might well be the difficult lives homesteaders went through to establish house and home. Man or woman, husband or wife—no one sat on their laurels. If a living were to be made, if a claim were to be improved, a life to be lived—if a loving home in the middle of all that openness were to be created, responsibilities had to be shared, equally. Equally.

Male and female created He them.

Saturday, May 11, 2024

Sunday Morning Meds --from Psalm 84

[An entire week off, not by my choice. I was kept away. Pain mostly. I think I'm on the way to recovery, but it'll be a long haul, I'm sure. Anyway, this Psalm meditation dates itself. If you know me at all, you can likely guess how old it is--we celebrated our 50th anniversary a couple of years ago.

Be back soon, I hope!)

“Blessed are those whose strength is in you,

who have set

their hearts on pilgrimage.”

I admire their idealism, what seems even their estimable foolhardiness, simply in tying the knot. Getting married is a good thing, the right thing to do, even if their second cousin (me) is likely to fumble through the ceremony In Protestant tradition marriage not a sacrament; but, Lord knows, it’s a big, big deal.

But I’m of the age when their sweet resolve to plunge into a legal and (somewhat) binding contract seems, well, dreamy in an adolescent way. The whole thing seems scary. They are so young and they are, really, so dumb. They’ve been dating seven years, which has the sound of something biblical. No matter: to the mind of any oldster, they don’t know squat.

In their mid-80s, my parents suddenly turned into scrappers, even though I don’t remember their ever being particularly cross with each other before, at least in my presence. They got in each others’ hair something awful. At the very end, do we really go it alone, like the medieval play Everyman so fearfully promises? Do even our closest relationships fail us? I don’t know.

What I know is this. Last night my wife and I skipped an end-of year gala and stayed home by ourselves, in part because we’re becoming less social, but also because in our 35-year marriage, right now nothing seems more blessed than being alone, just the two of us. Playing hooky on a gala was low-stakes. Couch potatoes get bad press.

I could try to explain all of that to this young couple—I’ve got to give a homily; I could tell them how we stayed home and simply enjoyed each other. I could try, but their being 22 means they wouldn’t begin to understand.

They’ve got their individual pilgrimage(s) ahead of them, just as we did, and my parents before us. Those two kids will be starting out on Sunday, and all the diagrams, the how-tos, all the counseling sessions we can offer will mean little to them because they’ll have to create their own map as they go, just as we did.

Marriages are a big, big deal for all of us really. Every cow-eyed young couple carries all our hopes with them when they recite their vows; because our hope, like theirs, is for nothing more or less than the first word of Psalm 85: 5—to be blessed.

I cannot imagine life without faith. Faith was the soul of our solitary night together, even though we didn’t recite bible verses. The two of us have spent hours and hours in prayer in our lives together, hours of pleading that sometimes seemed fruitless, but wasn’t. Guess what?--we’ll keep praying because faith isn’t something one wears like a tux; and we are blessed—as the psalmist says—by putting our faith in God. I know that’s true. Our pilgrimage, begun so long ago, continues. Our story continues to unfold.

I hope somewhere down the line we don’t start to carp at each other, but then, my mother would roll her eyes if I brought up the subject. “What do you know, really, about pilgrimage, young as you are?” she’d say. And she’d probably be right.

Sunday, May 05, 2024

Sunday Morning Meds--from Psalm 84

My mother thought the world of the college where I spent most of my professional life, and it’s right that she did—all three of her children went here and many of her grandchildren. She remembered the college’s founder fondly, as well as its second president. Her son taught here for thirty years. She believed in Dordt College. But let’s be clear: she lived 500 miles away.

Absence can make the heart grow fonder in institutions, just as in love. And—not to empty the cliché bin—familiarity has been known to breed some feisty contempt.

Benedictine monasteries are trendy places these days, in part because fine writers like Kathleen Norris make them seem a bromide to the desperation of our lives. But her own work makes clear that people don’t check their sin at the door when they walk into the abbey. I know churches where preachers on staff can barely speak to each other. The average term of office for a youth pastor today is little more than a fortnight, I’m told, in part because so many of them can’t get along with their often less cool superiors. Churches are not heaven.

Distance is sometimes delightful, comfortable. Landscapes can be beautiful; close-ups can be brutal. I’m not all that sure the Psalmist is talking about a building—that’s what I’m saying.

If what this verse emphasis were true, what do we do with Eli, the priest at the door of the temple? By all accounts, he was a fine man, but he couldn’t control his boys, who dallied indecorously with the women who worked right there. Neither Hophni and Phinehas, nor their paramours, despite the immediacy of their temple tasks, were “ever praising” God, as the Psalmist so dreamily envisions here in verse three.

Psalm 84 is an exile psalm, and its exaltation of the temple is, in a way, but a mirror image of the horrific emotional deficit the psalmist feels when he’s not where he wants to be. So he wants what he can’t have. He longs to return to a place far away, a place where he can’t go, where everything is perfect, where the pious are all praising God.

Is there such a place? Only in your dreams.

I don’t know what Hebrew word Bible translators located in this verse and then converted into our dwell, but that choice feels right to me because the roots of the word dwell in Old English and Old Frisian are, oddly enough, in wandering. To dwell is a phrase that has buried within it a history of having wandered, of having been apart. That’s precisely the position of the psalmist. He wants badly what he can’t have.

And it’s us too, even though there’s no sacred temple locked up in my memory. Three- count ‘em, three—women we know well are doing very poorly right now, trying to fight the cancer that not only threatens but already cripples. They’re not just skirmishing. We’re talking all-out war.

A man who sat here not twenty feet from this chair not long ago took a nap a week or so ago and never woke up. Sixty killed yesterday when a suicide bomber did his thing in Baghdad. Hundreds of Cubans are in Panama, trying to hike to the U.S., whole families, darling little kids. Millions are fleeing Syria.

Sometimes we feel horribly exiled and we wish so badly to dwell in the House of the Lord.

“Blessed are those who dwell in your house; they are ever praising you.”

Lord Jesus, come quickly.

.JPG)