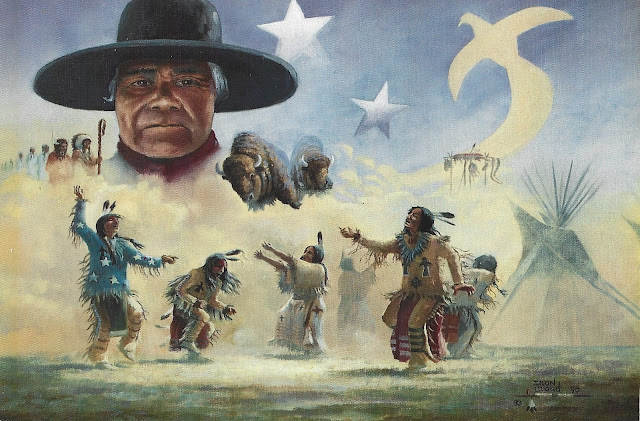

The Ghost Dance, one of the saddest religions of all time, a frenetic hobgoblin of Christianity, mysticism, Native ritual, and sheer

desperation, swept up Native life throughout the west in the final

years of the 19th century.

Then dance—women and men together—dance around that sapling, dance and dance and dance and don’t stop until you fall from physical exhaustion and spiritual plenitude, dance until the mind numbs and the spirit emerges. Dance into frenzy. Dance into religious ecstasy.

“The great underlying principle of the Ghost dance doctrine,” says James Mooney, “is that the whole Indian race, living and dead, will be reunited upon a regenerated earth, to live a life of aboriginal happiness, forever free from death, disease, and misery.” It was that simple and that compelling a heavenly vision.

As a white Christian, I am ashamed to admit that in the summer of 1890, the desperation of Native people, fueled by poverty, malnutrition, and the death of a culture, created a religion that played a tragic role in the massacre at Wounded Knee.

It’s easy for many of us to read the opening two verses of Psalm 42, the song of man or woman in exile, as if we’ve actually felt the thirst David is talking about. But it’s helpful for me, a white Christian, to know the story of the Ghost Dance, to understand how thirstily Native people looked to a God who had seemingly left them behind. They were dying, both spiritually and physically. They felt that abandoned.

Thirsty four-leggeds in the opening lines of the song would make sense to Native people; they would have understood the opening bars of David’s song.

What’s at the bottom of this lament is God’s horrific absence. Humankind has all too abundant a history of abject, dire need.

I’m not at all thankful for the story of the Ghost Dance, or even of David’s desperation recorded here in this memorable psalm. But I am comforted in the knowledge that when my bootless cries seem to disappear into the wide-open spaces of the plains where I live, I know I’m not the first to feel abandoned--even a poet/King "closest to God's heart" felt the strangling clutches of despair. We are not alone--

The gift of grace in the near despair of the opening lines of Psalm 42, or so it seems to me, is, once again, that neither you nor I nor the person down the street suffering far more than we are is ever really alone.

No comments:

Post a Comment