This illustration was standing proudly in the Heard Museum, Phoenix, Arizona, this summer, when we stopped by. I took out my phone and took a picture because the source of the image--it is an illustration--is a book I recognized immediately, a collection of stories by Francis LeFlesche, who grew up on the Omaha Reservation and did incredibly admirable work in documenting the traditional lives of his Omaha people, including their songs.

|

| Francis La Flesche |

I'd read Francis LeFlesche's The Middle Five, and read it appreciatively as a contribution to the peculiar American story of kid raised in an era when straddling two cultures--his own Omaha heritage and the powerful colonial interests of the white culture--was a way of life none really could sidestep. Encroaching from every corner of the reservation was a Euro-American world with different values and different sins. Not that long before his birth, the white man had been little more than a rumor. Francis LeFlesche--like his sisters--had attended a Presbyterian boarding school on the reservation, where he'd learned things most Omaha boys hadn't, things about the white man's world, both from curriculum and not at all.

The Middle Five is a collection of interwoven stories that follow the lives of the Native boys who attend that school--not all Omaha boys do. As such, it sheds light on the whole boarding school experience/phenomenon, although in Francis's case his boarding school education did not move him far, far away from his home, as many Native kids so educated were. What the stories capture--and the best ones are a treasure--is the disconnect all Native kids and their parents went through in the last half of the 19th century particularly, specifically a powerful push to assimilate into the dominant white culture, something they could do, it seemed, only by rejecting traditional tribal ways.

I snapped the picture only because I'd read the book that contained the illustration. I don't remember that I even read the name of the artist. It was a picture I remembered from the book, from the story of a little Winnebago boy sort of lost on the Omaha reservation.

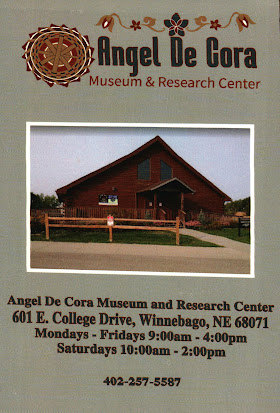

Just this week, during a trip around the Omaha and Winnebago reservations, we stopped at the Angel De Cora Museum and Research Center in Winnebago, Nebraska, where I discovered that the woman who had done that illustration in the Heard Museum was from just south of here and that she almost certainly knew Francis LaFlesche, who grew up just down the road, an Omaha.What's more, the two of them, contemporaries, struggled, each in their own way, to create a new culture amid the strewn wreckage of what was old and dear, and would or could never return. Both of them effectively made their way in a new world, but never reneged on their belief in and commitments to the old ways. Both worked hard to reclaim a heritage they loved. They were, in a way, cross-cultural operatives, as maybe all of us are, some of us simply strung on far sharper opposites.

It's less amazing than it is gratifying to know that both of them, long after their respective deaths, continue to bless the cultural heritage of their respective communities in such public ways.

I want to learn more.

No comments:

Post a Comment