Let's give them this much. American Christians didn't really understand the guy. After all, here he was, a George peanut farmer with honest-to-goodness rural roots, but he still hung on to political positions you better understood when they were uttered by politicians from San Francisco or Harvard Yard. He was a Southerner, by heritage and accent, but he talked about justice and freedom as if he was aboard one of those buses full of trouble-makers.

How do you reckon a man who brings duplicate photographs of the men in the talks he created at Camp David and, in one fell swoop, thereby saved the diplomacy he'd originated from utter disaster, actually did something about the madness in the middle east. Jimmy Carter did incredible things, then next Sunday, taught Sunday School at a little Baptist church in Plains, Georgia? Really.

American evangelicals either didn't know a verifiable Christian when they saw him or her, or else they just didn't care.

And, honestly, why should they? In any election, no one is voting for a pastor; they're all voting for a President. So, if you have a choice between this Baptist peanut farmer and, this round, a big guy with bad hair and big bucks, a bad-ass jerk who runs a court system like a mob boss, you take the bad-ass.

If you want a great preacher who lives by commandments, go to church. If you want a great President, recruit some monster who writes his own rules.

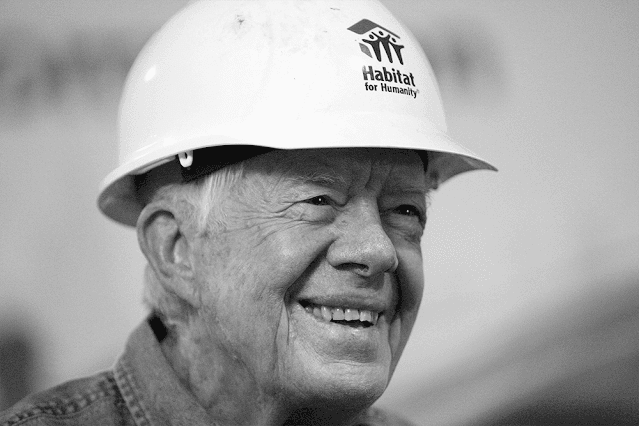

Jimmy Carter died yesterday. He was 100 years old. He was a testimony to God's love, a man who tried to make and bring peace on earth. Inflation got way out of hand, hostages stayed far too long in hostile Iran, and the American electorate began to suspect that they could do better than a Sunday School teacher. So he was voted out after one term and forever after known as a loser. But that was the election of 1980. The Carters--you couldn't really separate them--went back to rural Georgia and determined they'd do what they could, with the help of the Almighty, to bring peace to places they'd never been.

So they did. Their story is a moral lesson in the days of Donald Trump. In the county where I live, where there are more devout Christians per square mile than almost anywhere in America, 85 percent of the populace voted for our incoming President.

It's impossible to imagine two people more decidedly different than those two Presidents. In 1980, 76 percent of the county voted for Ronald Reagan, 19 percent for Jimmy Carter. In November of this year, let me say it again, 85 percent of county voters chose Donald J. Trump.

Some wonder whether the country is moving in the right direction. Really, some do.