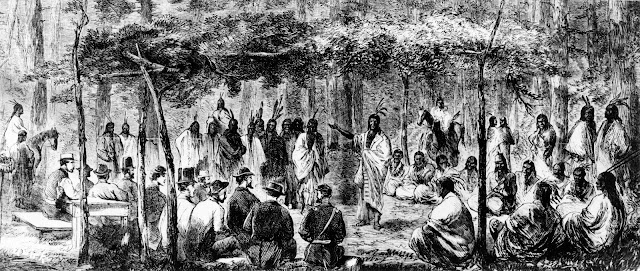

Did I mention the army? Add to that 15,000 an additional 500 men in blue to protect the peace commissioners out there at the confluence of Medicine Lodge and Elm Rivers, all of them determined to settle the mess created by a mad rush of Euro-Americans to occupy every last stretch of fertile land--and even some not-so-fertile--that they could call their own, even though that land had its own people with their own history and culture, the Kiowa, Comanche, Arapahoe, Apache, and Cheyenne. Those people were at Medicine Lodge--15,000 of them, in fact, close to the border of Kansas and what was then Indian Territory, today is Oklahoma.

The Historical Marker right there at the spot has it right: "While the treaties did not bring immediate peace," the sign says, "they made possible the coming of the railroads and eventual settlement." Sure. That's like saying that 9/11 was a plane crash.

The Medicine Lodge Treaties are almost always spoken of as plural because when those peace commissioners and the Native headmen signed them, there were more than one--three, in fact. The whole gathering was much ballyhooed because any multitude of that size--and almost all of the folks there gathered in their own colors--was going to draw attention. The Medicine Lodge Treaties certainly did, newspapermen all the way from New York City. Seriously.

For years already, blood had flowed throughout the region, our world, the world of the Great Plains. The Peace Commission, full of righteousness, determined to end bloodshed by treaties that established extensive land concessions and defined the boundaries of a reservation that covered most of what is today southwestern Oklahoma. Those Natives who signed thereby surrendered their claims to more than 140,000 square miles of land. In return, they were sentenced to a measly 5,500, but--listen to this!--they'd receive payments of $25,000 per year for 30 years, or so they were promised, and annuities--food, supplies, seeds, and farming equipment that never came, and oh, yes, the promise of schools and churches.

The Medicine Lodge Treaties, white people got the land and Natives got what white people called a holy book. Oh my, they should be grateful.

The Medicine Lodge Treaties of 1867 opened up all that land for settlement by American dreamers and an bellowing iron horse that miraculously linked East coast business interests with gold fields and a burgeoning West coast world once impossibly far away.

After the treaties, the only impediment to burgeoning national business interests was this lousy, stinky crowd of smelly, scruffy monsters, the American buffalo. When men like our own General Dodge, Council Bluffs' most famous founder and a railroad genius, looked at those lousy buffalo on and just off his precious Union Pacific tracks, there arose a great thought in the minds of the railroad people--kill the buffalo, make it a sport, and we'll simultaneously destroy the menace of that Native world.

In the early years of the 19th century, 30 to 40 million bison were here in our world. Lewis and Clark spotted their very first herd from the top of Spirit Mound, not even an hour away. Astonishingly, by 1895, only a thousand were left. In 1873 alone, the hide yard in Dodge City, close to the Medicine Lodge River, shipped 200,000 hides and had another 80,000 in their warehouse.

"While the treaties did not bring immediate peace," the sign says, "they made possible the railroads and eventual settlement."

Did they ever.

In 1867, 15 thousand Native Americans gathered at the confluence of the Medicine Lodge and Elm Rivers in southern Kansas to hammer out a lasting treaty that would establish peace on the plains.

Didn't. Nope.

I can't help but think that this is the kind of story nice white kids aren't supposed to hear. What underlies this entire narrative is--be careful now!--Critical Race Theory.

Can you imagine shooting buffalo right out of the open windows of a passenger car on the Union Pacific? What a hoot!