His reasoning went something like this: what the white men will teach you isn't necessarily right, but it's good--and those who believe it at the Rehoboth mission are good; therefore what they teach may well bring you into "the beauty way," the way of love and respect.

So, decades ago, still a boy, he went off to the school at the mission. Today, he's a believer, a Christian.

2. We're walking around the village, strangers to be sure, two of us white and American in the middle of a busy Mali village of 500 souls, maybe more, in a rural area where most villages are little more than extended family compounds. Sheep and goats, chickens and dogs wander everywhere. In rural, sub-Saharan Africa, people sleep under roofs and within walls but generally live outside.

We're walking along a street and passing the mosque--you can't miss it because it's kept up well by Khadafi's oil billions--when out walks the imam. Go ahead and imagine him. He looks exactly like you might think, bearded, capped, shawled, long and colorful robes. He stops us. We hadn't knocked or tried to sneak into the mosque.

Out he comes. "Let me tell you about him," the imam says, and points at our tour guide, the head of the medical clinic just outside the village. The mullah came out to meet us because he needed to be sure we knew what a tremendous blessing this man, a Christian, has been to the whole village. May Allah be praised.

3. It's the house of the senator of the region, something like that. The political position doesn't really have an equivalent here, but in Niger he's the official representative of the national government; and we're there at his house, his compound, eating his food and drinking his bottled water because he's very proud to tell us that the man we're with, the man who, with his wife, has created a medical clinic in town, is a wonderful man who is doing great work.

It's been a holiday, the Feast of Tabaski, and everywhere there are picnics, barbeques, family reunions. People are adorned in their finery, their most outlandish jewelry and brand new colorful dresses. It's a festival of biblical proportions. Everyone in the city, save just a few, is Muslim--everyone. As is the senator, his wife, the house guests who happen to be visiting when we drop by, the servants who bring us food and drink, and the armed military parked just outside his place. But the politician makes very sure we know that this Christian medical man is a great gift, even though he is, by definition, a heathen.

4. In a Sunday op-ed, Nicholas Kristof, who is not an evangelical, offers some remarkable testimony about evangelicals: "I must say that a disproportionate share of the aid workers I’ve met in the wildest places over the years, long after anyone sensible had evacuated, have been evangelicals, nuns or priests.

Case in point, Kristof says, Dr. Stephen Foster, 65, the son and grandson of African missionaries, who has himself spent his lifetime caring for Angolans who, in his region especially, suffer horrendous infant mortality rates. He's white, he's Christian, and he's been there forever.

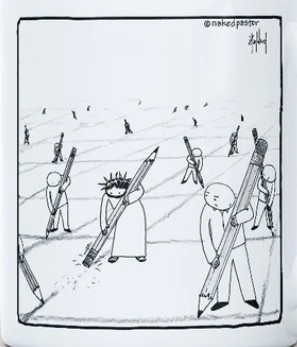

5. Holy Week, begins with a parade, the Lord of life, the King of Heaven and earth, coming into a town a celebrity. But long before the parade began, he determined that this triumphal entry was something he'd do on a donkey, a braying ass. That's how he came to us.

That's what he was, a servant.