I remember a certain species of goosebumps, my first. I was twelve years old maybe, part of a choir festival a half century ago in a small town in Wisconsin, dozens of kids drawn from a dozen Christian schools. The music was Bach—“Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring.” For almost fifty years I’ve not been able to hear that piece without remembering that day. My entire self—heart, soul, mind, and strength—reacted to the beauty.

Those goosebumps arrived in an afternoon rehearsal before the big concert that night. I remember what that gym looked like, which step I occupied on the bleachers, and some of the kids who stood around me; and I remember being embarrassed because this unmanly tearful impulse, this odd soul tremor was a threat that required whatever testosterone I had to stifle. Something weird in me made tears arise.

The music was gorgeous. I didn't know Bach from Beethoven, but I knew what we were singing was glorious. But my girlfriend was there, and I haven’t forgotten that either. She stood a row or two beneath me in the choir, and her being there was part of this odd emotional seizure. The music alone would not have raised such a visceral reaction. My seeing her, a row or two beneath me was part of the moment too.

And faith played a role too—we were singing about Jesus, of course, and we were all kids from Christian schools; and then there was the beautiful music—we couldn’t do much better than Bach; and my girlfriend—well, I suppose most of us experience love long before we can define it. Being part of something so much bigger than myself had to play a role too—all these kids were making a beautiful, joyful noise.

Psalm 147 says, first thing out of the box, how pleasant it is praise him—how pleasant. It’s an amazingly human assertion: "Sheesh, praising God feels good." The first declaration of this psalm has nothing to do with duty (“we should praise him”) or his wanting our praise. Instead, the psalm starts with all of us from the Me Generation: hey, praising God just plain feels good. And, oh yeah, it’s fitting too.

I wonder whether my skin turned inside out and my tears ducts threatened because, maybe for the first time, my “self” disappeared. I got lost in the music, lost in affection, lost in the joyful affirmation of group love that is choral music, lost in all those things, lost in plain beauty, just flat-out lost, lost in praise.

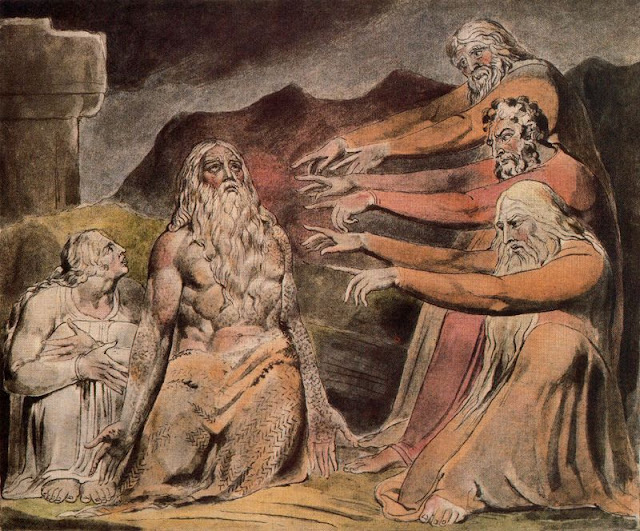

Just about every great religion maintains that self-lessness is a good, good thing. Love is selfless. Heroism is selfless. Vivid spiritual experience is always selfless. When Mariane Pearl heard of her husband Danny’s brutal execution at the hands of terrorists some years ago, she said she was able to handle it because she’d been chanting. She’s Hindu. “The real benefit of having practiced and chanted was that at that moment was that I was so clear on what was going on. This is a time when I didn’t think about myself at all,” she says. And that was a gift.

Sometimes it’s just good to lose yourself. It’s good to praise, to give yourself to God. It’s good to love, to give yourself away. Praise—whether it’s evoked by a Bach chorale or bright new dawn—gives us a chance to empty ourselves.

And that’s good, and it’s pleasant,

and it’s fitting before the King—our King, the joy of man’s desiring.