|

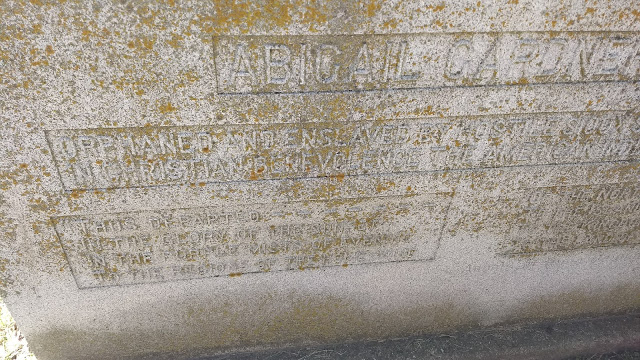

| Del Iron Cloud Going Home |

What both illustrations of the Fool Soldiers' rescue share is the single horse and travois, and a warrior--in this case, two warriors--looking behind them. Even though they'd argued successfully and given up whatever they'd brought with them in exchange--horses, blankets, guns; even though they had the hostages with them, even though they were well on their way back to Ft. Pierre, they were scared to death that White Lodge and his band would catch up with them, take back the captives, and get rid of "the boys."

The most reasonable explanation for their behavior is a dream/vision one of them swore came to him unbidden. A herd of elk arose and the biggest one approached and spoke to him, a young warrior named Kills Game. “There will be ten of you,” that elk told him. “You must be strong and respected.” It was neither odd or strange for a warrior to hear that directive, bravery and courage being foremost among the attributes of warriors.

Charger called the others together to consider what the elk’s prophecy might mean for the warrior society they had named, the Strong Heart Society. His interpretation began with something his father had told him, that being that dreams are often “contrary” visions, meant to be understood in opposite ways to what they might explain themselves to be.

No one will ever know, of course. However "the boys" described their motivations is buried in an unreachable past by this time. What remains is simply the story of their foolish heroism. The accepted motivation for what they did is the dream--and its interpretation to do the opposite of what that big elk spoke.

But there is another. When her nine children were out and on their own, Josephine Waggoner, a Hunkpapa Sioux from Standing Rock reservation, went on a mission. What was happening all around was the deaths of the old ones, who remembered the days before the white man, the old ways. They were dying.

She'd learned English at Hampton. When she returned to Standing Rock, she translated sermons for both the Episcopalians and the Roman Catholics, as well as letters Sitting Bull, also a Hunkpapa, received from lots of fans (he'd become something of a celebrity). When Sitting Bull was killed, she'd helped lay his body out in traditional ways for his burial.

What resulted is a sprawling series of narratives taken directly from the heart and the lips of the old ones. The manuscript she put together took years to get published because oral history--the only kind of history the old ones knew--had no footnotes. It couldn't be documented, as white man's history must be. However can we trust the veracity, the truth, of what some old people say? some publishers told her. It's impossible.

So Josephine Waggoner's Witness: A Hunkpapa Historian's Strong-Heart Song of the Lakota wasn't published until 2014, long after her death.

Amazingly, there's another story of origins in Witness, an explanation for the almost insane foolishness of the Fool Soldiers, an explanation that is real soul food.

That story, tomorrow.

|

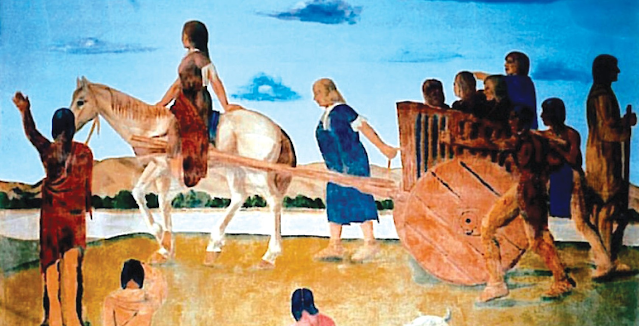

| The Shetek hostages |