I came upon News of the World the old way, by reading the novel, which I liked very much, by the way, didn't quite love it, but liked it a heckuva lot.

[It's only in theaters right now, so you've got to brave Covid. There were, I think, six of us there on Monday night, social distance wasn't a problem.)

It's a very simple story. In fact, most things about the story are simple. The devotion Captain Jefferson Kyle Kidd (Tom Hanks) pays to Johanna Leonberger (Helena Zengel), the child who's become his charge, is simple. He determines to bring her to her people, German immigrants somewhere near the the Texas Hill Country. No law makes him do that, no force is applied other than his conscience. He's not making a dime either. What pushes him is the sure knowledge that if he doesn't do it, no one will and the unspoken conviction that it's not just a good thing, but the right thing to do.

Despite her beach blonde hair, Johanna is a far cry more Native than she is German-American. Some years before, her parents were killed by the Kiowas who kept her, brought her up, and obviously took care to love her. She'd much prefer them to whatever awaits her at the end of a pilgrimage she neither chose nor, at least initially, desires--and knows nothing of.

But what she slowly begins to understand--even though she speaks only Kiowa and then not much of that either--is that this odd old Civil War hero is no beast in a world where there is shortage of beasts, many of them in fact in the post-war Reconstruction era. Lawlessness on the frontier is the rule, which the movie and the book make clear from the very start. Johanna, who has no recollection of her former life, has no future worth living outside the protection of Captain Kidd. She's savvy enough to know it.

News of the World is not complex. Through some very difficult times, the Captain brings his stoic, silent charge back to an uncle and aunt who are surprised she's alive, but are as heavy on the justice as they are short on the mercy.

Spoiler Alert. When I say it's a simple story, I also mean to say it has few plot surprises. The Captain brings her to a home that really isn't a home and thus ends up with her, a kind of daughter, which is fitting for a man who lost a great deal in war that's just concluded.

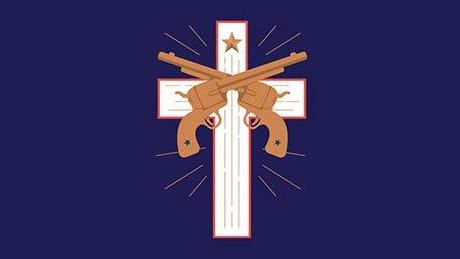

Let's not be shy here--News of the World is a Western, an old-fashioned Western with horses and wagons and Indians and outlaws. It's dusty and woebegone out there in the Texas no-man's land, where the man with the biggest guns wins. But it's a Western in today's cultural world: the Kiowa are a far better people than the white men, who are gravely addled by a long, bloody war they just lost.

When the two of them find their way into a camp of buffalo hunters, Johanna is distraught surrounded as she is by carcasses being stripped, by the wanton, bloody slaughter of an animal her Kiowa family taught her to respect. She is not just stunned, she's mortified, as if a statue of Mary was defiled. Quietly, in Kiowa, she sings her misery because her Native family has blessed Johanna with their ways. She's a wonder. Helena Zengel will likely never have another beautiful, starring role in which she says so very, very little.

Tom Hanks is this Western's John Wayne, but the savages in News of the World are white men. And, truth be told, the Captain, who ranges through frontier Texas reading news from around the world, is a traveling national magazine who brings his own bit of culture to a world where what little there is is dispicable. He comes to bring peace to frontier towns, not a sword.

The weakness of the novel and the film is that it doesn't offer any surprise. All turns out for the best when the credits role.

But I say, that's reason enough to walk through the turnstiles. 2020 was no winner. News of the World is. Goodness, truth, mercy, commitment, love--they're are the heart of the News of the World, a healthy bromide as a truly love-starved year--thank goodness!--fades into well-earned oblivion.

flat

flat