|

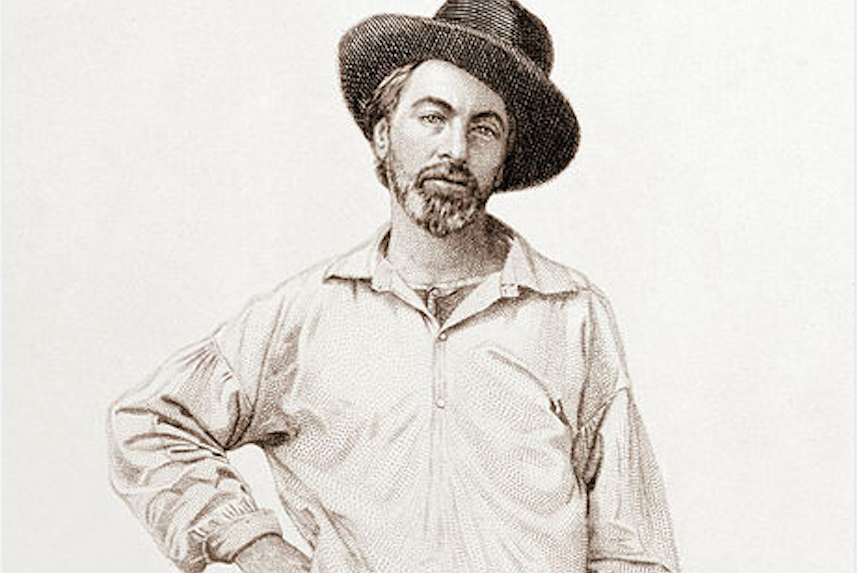

| Whitman, the pose he loved |

Take a deep breath. This single sentence ambles along for a decade or so.

For years past, thousands of people in New York, in Brooklyn, in Boston, in New Orleans, and latterly in Washington, have seen, even as I saw two hours ago, tallying, one might say, the streets of our American cities, and fit to have for his background and accessories their streaming populations and ample and rich façades, a man of striking masculine beauty—a poet—powerful and venerable in appearance; large, calm, superbly formed; oftenest clad in the careless, rough, and always picturesque costume of the common people; resembling, and generally taken by strangers for some great mechanic or stevedore, or seaman, or grand laborer of one kind or another; and passing slowly in this guise, with nonchalant and haughty step along the pavement, with the sunlight and shadows falling around him.Supposedly, it's from the pen of a man named William Douglas O'Connor, who is defending the American poet Walt Whitman, the character described in that book-length sentence. There lies a tale.

Whitman, who shook my timbers when I took American Literature in my sophomore year in college, was, well, "an outfit," as my mother-in-law used to say about those who wandered substantively from the norm. And Whitman did every way.

The atmosphere is not a perfume, it has no taste of the distillation, it is odorless,Dozens of such lines (from "Song of Myself") weren't standard poetic fare in 1865. Shoot, they're hardly standard today. I doubt they've ever been printed on a Hallmark Card, despite the fact that most every kid who's ever taken American Lit had to read them, as I did, at one time or another--and as I assigned them to be read for forty classroom years.

It is for my mouth forever, I am in love with it,

I will go to the bank by the wood and become undisguised and naked,

I am mad for it to be in contact with me.

Such weird swagger was sacrilege to some--to Willa Cather, for instance, half a century later, in fact. Yet today, I'm guessing some parents would rather that Whitman be politely passed over during classroom discussion. How many people you know howl about how much he enjoys the scent of his own armpits.

It's understandable why a senator, from Iowa no less, and Mr. James Harlan, would go ballistic when he discovered that unrighteous Walt Whitman was working for the government of the United States, a low-level clerk in the Department of the Interior to be sure, but just the same--that hedonist on the government payroll? Say it ain't so, Sen. Harlan screamed. Something has to be done.

And something was. Didn't take long and Sen. James Harlan, he of the Tall Corn State, had Walt Whitman fired.

That's when William Douglas O'Connor--he of that long gracious sentence above--came to the poet's defense, both in words--

He has given his thought, his life, to this beautiful ambition, and, still young, he has grown gray in its service. He has never married; like Giordano Bruno, he has made Thought in the service of his fellow-creatures his bella donna, his best beloved, his bride. His patriotism is boundless. It is no intellectual sentiment; it is a personal passion.--as well as in action, getting Whitman yet another low-level position in the office of the Attorney General. "The Good Gray Poet," a long essay O'Connor penned, slowly altered the view of Walt Whitman held by thousands of Americans.

(A secret? There are those who think O'Connor never touched a pen to paper. There are those who believe the man who wrote all that puffery was named Whitman. Hey, mum's the word.)

And Whitman? --I can't imagine he changed a bit, eccentric, yet personable, outrageous yet oddly reverent about the whole idea, the promise of democracy, of America. Whether you like him or even understand him, Leaves in Grass is in every last American Lit anthology, and deservedly so.

About James Harlan I don't know much. I'll look him up.

And Whitman? --I can't imagine he changed a bit, eccentric, yet personable, outrageous yet oddly reverent about the whole idea, the promise of democracy, of America. Whether you like him or even understand him, Leaves in Grass is in every last American Lit anthology, and deservedly so.

About James Harlan I don't know much. I'll look him up.

Give him this at least--the Senator from the Tall Corn State at least made the history books--a footnote maybe, but he's there, 150 years later, still in the wardrobe of a prune.

Today is Whitman's birthday.

Just sayin'.