I have no memories of a short speech given by a stocky

African-American woman named Fannie Lou Hamer, a woman who was pleading the

case of a delegation of Mississippians, most of them black, asking for voting

credentials at the 1964 Democratic convention. Our family television wouldn’t

have been on. We were, after all, Republicans.

Hamer had a sixth-grade education and no more because her little hands

were needed in the cottonfields, where her family tried to make a life from

sharecropping. She started picking cotton when she was six years old.

When Fannie Lou Hamer told the 1964 Democratic Convention what she'd suffered--a horrible beating while jailed in Winona, Mississippi on some ridiculous charge--delegates were stunned. Lyndon Baines Johnson, who had been President for less than a year and who, down the road, distinguished himself boldly and wonderfully for the cause of civil rights in this country, was scared to death he'd lose the votes of the Dixiecrats to the Republicans if they heard Hamer's go on and on about racism down South.

Johnson was so scared he called the networks to interrupt the Ms.

Hamer's testimony to tell them he was having an unscheduled news conference. So

they simply turned out the lights on Fannie Lou Hamer and started broadcasting

from the Oval Office, where LBJ told the nation it was, at that moment, nine

months since the death of President Kennedy. That's all he said because there

was no news, only subterfuge.

Johnson kept Fannie Lou Hamer's testimony from a national

audience. That happened. That actually happened.

I never knew any of that until I read James H. Cone's The Cross and the Lynching Tree, a reprimand, an indictment against "Christian" America. Cone's book is a Jeremiad that's wilting in every way possible--culturally, morally, spiritually--to the white folks at whom he aims, most specifically those who confess the name of Jesus.

Cone makes you weep, makes you wonder where you were in 1964, where you were for a half-century or more of terrifying bloodletting when white racists, church-going folks, pulled out ropes from their sheds and hung black men--and some black women to keep n______s in their place.

If you're a white and Christian, The Cross and the Lynching Tree will teach you things you didn't know, things you can't help but wonder how you missed. It will make you wonder where you've been.

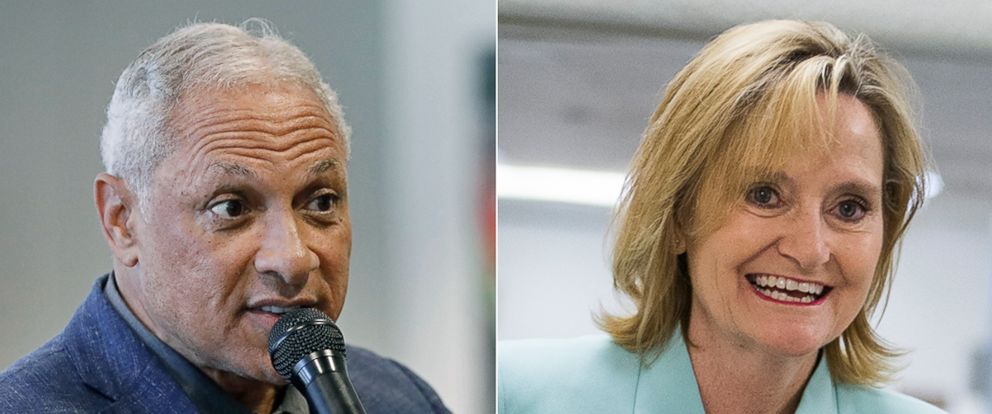

Doubtless, Cone made me more sensitive to the

effects of the strange line Senator Cindy Hyde-Smith used in describing her

appreciation of a donor: "If he invited me to a public hanging," Hyde Smith

said to the supporter, "I'd be on the front row."

No mention of race in that word picture, right? It’s just

the Senator and that donor, front and center of a crowd gathered before a dead man hanging in front of them.

But what she knows only too well is that such things happened in

her neighborhood with some horrifying regularity. Mississippi had the highest number

of lynchings from 1882-1968 with 581. Almost 80 per cent of the 4373 lynching happened

in the South; of them, 3446 victims were black.

I don’t consider myself a foot soldier in the PC army, but Cone’s The Cross and the Lynching Tree has made this old, white Yankee sensitive enough to understand the furor over

what I might have otherwise considered Ms. Hyde-Smith’s casual, off-hand aside.

You can’t conjure an image of a public hanging in Mississippi without

blackening the face of the victim. The idea of that donor and the Senator in

the front row prompts too much of a horror story that’s not been forgotten--and shouldn't be.

Whether Mississippians vote for Cindy Hyde-Smith or Mike Espy, her

African-American opponent, isn’t my call. But without a doubt, she did the

right thing by apologizing. It's the least she could do.

I do not remember reading about Fannie Lou Hamer in Robert A. Caro's books. LBJ is portrayed as a psycopath, but too much got left out. Maybe I can get my money back.

ReplyDeletethanks,

Jerry