Morning Thanks

Garrison Keillor once said we'd all be better off if we all started the day by giving thanks for just one thing. I'll try.

Tuesday, July 31, 2018

Walking

Horses were an unintended gift from Coronado or DeSoto, when one of the Spanish invaders left a gate open some sleepy night in New Mexico, and thus changed life forever among Native tribes from sea to shining sea. Imagine you're a 16th century Arapaho. You go all slack-jawed when one day some Comanche comes riding up on the biggest dog you'd ever seen. What a joy for a nomadic people. What a unexpected blessing.

I dare say there are more horses per capita on reservations than there are in any suburb of the nation, despite the fact that very few horse owners make a dime on 'em.

Still, you know you're on a reservation when you see random people walking--on state roads, county blacktops, or low-maintenance gravel. All those horses notwithstanding, First Nation folks just walk a whole lot more than white folks, it seems. Wealth has something to do with it, I'm sure, and some people just don't have cars. But reservation culture appears to smile at pedestrians: no one disdains men and women and children who walk to town, despite the significant distances.

There was a time when Natives weren't the only pedestrians. When a gang of Hollanders left the lakeshore in Wisconsin and struck out for the Nebraska grasslands, they were happy to leave an axe or two behind. The only way to the conquer Wisconsin woods was to fell trees. Then fell more. Then fell even more. Then dig up roots--back-breaking work. Only when you got out the trees could you put in a crop.

Nebraska, people said, was a miracle, treeless, nothing but an ocean of grass. Here and there a few cottonwoods sprouted from some wayward creek or river, but basically the world all around was as open as it was free. When some Hollanders got to a place called South Pass Precinct, they'd walked, dozens and dozens of miles.

Soon after the Civil War, a man named Huizenveldt looked to homestead Nebraska land around a new Dutch colony, only to find all kinds of stone piles marking claims others had already made. So he kept going, west, until all that land seemed free. Ten miles west of the colony he found the spaces open. The next morning he walked to Lincoln to register it as his--25 miles or so--then returned to the colony, where he was staying. Then, for a long time, he dug out a place for his family in the land he wanted to work. People in the colony were nice enough to put him up, but his claim was ten miles away. No matter. Every day he walked. There and back. Every day. Let me do the math--that's 20 miles a day.

A man named Alco Vandertook (yes, to me too the spellings seem wrong) became a good friend of a preacher named Dominie Huizenga and another man named Den Herder, both of whom were looking for Nebraska land. When Brother Alco found railroad land he thought his two friends might like, he walked to the courthouse at Lincoln to make it his--for them. That was, as I said, 25 miles. The thing is, he was so determined to get that land that he showed up at dawn.

Simply to imagine that is painful.

J. H. TeSelle left Wisconsin to homestead Nebraska prairie, determined to open up the virgin soil beneath grasses that had grown there since time began. Thing is, TeSelle lacked a plow. Blessedly, his neighbor had one, a neighbor who claimed he'd be happy lend it. Only problem was conveyance. TeSelle had no choice, so he carried it, a whole breaking plow, for the several miles that separated him from his neighbor.

In order to invest as he wanted, one father and husband worked as a hired man, walked twenty miles on Monday morning to work, then didn't return until Saturday. But before he'd come home at the end of the week, he'd pick up the groceries--flour, potatoes, what not else--and lug it all on his back to his wife and kids, twenty miles.

Alright, I'll admit it. This summer, more than once (but not more than thrice) I've taken the four-wheeler to the mailbox, which is less than a block away. That only happened after a long day out back or two-mile walk on the gravel roads all around or the Puddle Jumper, a mile away in Alton (and, yes, I take the car to get there). From our old place we would occasionally walk to the post office, a mile or so south; but that's it.

You can't help but wonder what it might have been like to walk 25 miles over open prairie, not a light on anywhere but the sky, the world a moonscape in the semi-darkness.

Sounds as beautiful as it must have been mystifying, but I think I'd take the four-wheeler.

Monday, July 30, 2018

Morning Thanks--Sabbath

Ever since we've moved, we've been, well, homeless, when it comes to church. That's neither confession nor indictment, because if it's a fair assessment, it's a condition we've created ourselves. If we are homeless, we are so by choice.

We've still got a membership, and, about half the time, we attend worship at the place we have for decades. But that church is something less than a half hour away, and I still--five years after we've moved--can't help but think it's crazy to make that pilgrimage when literally dozens of wonderfully accepting venues sit just down the road.

Still, for two people who kept the Sabbath for 65 years by attending church religiously, not once but twice every Sunday, this hit-and-miss thing we're up to is both sweet and sour. Yesterday, we stayed home in the morning. I sat outside out back and read an odd old book about the Dutch in Nebraska. Maybe sitting in the silent sunshine shouldn't be called "worship," but the word should just seems like unnecessary baggage when far more life lies behind you than ahead. If what I did with my Sunday morning yesterday wasn't worship, I don't care to hear.

Besides, we'd determined we'd still go twice: once in the home with Dad, who's 99; and once a half hour away at a place we can most safely call "home." We had a beautifully silent Sunday morning out here in the country, and still maintained the old quota.

Chapel at the Prairie Ridge Home isn't particularly exciting. A little more than half of those who attend know where they are. More often than not, visiting preachers will rehash an old sermon; but theirs is a tough job because it's as easy to talk down to the elderly as it is to fly over their heads. The good preachers try really hard, and some churches bring a whole crowd, which is a joy. Yesterday, things were, well, perfunctory. But then grace abounds simply in seeing Dad sing words he can't read but know by heart.

Afterward, we stay for coffee around a table in the dining room. The faces change almost weekly, because people come and go with startling regularity at Prairie Ridge. Residents aren't particularly happy to be there, but no one ever walks away on their own. Still, a half hour of conversation is likely more than most of them get on a good day.

Last night, I couldn't help but think one of my own colleagues, a man who had a lot to do with the design of First Church, where we went at night, wasn't right about big, roomy worship spaces, even though "with it" churches today choose bowling alleys and ex-car dealerships for sanctuaries, bringing Jesus to the world. First Church isn't an old church, but it's old school, big and roomy and resonant, so there's room for the organ, itself a relic.

It was a wonderful service, a profession of faith by a young lady, daughter of friends; congregational prayer by an old man, once a colleague; sermon by a young preacher, also a friend, a man doesn't shy away from the prophets. And, oh, yes, astonishing music from the best violinist in the county. And then, after all of that, we celebrated communion.

All tolled, not a bad Sunday at all for a couple of homeless people. Not bad at all.

This morning, I'm thankful, really thankful, for yesterday, the Sabbath.

Sunday, July 29, 2018

Sunday Morning Meds--A Good Night's Sleep

“I will lie down and sleep in peace,

for you alone, O Lord,

make me dwell in safety.”

Psalm 4 is “the evening hymn,” not because of the demands it

makes for God’s ear in the first verse, or because of the 12-step program it

outlines for those of us who don’t know the Lord (in vs. 3, 4, and 5). Psalm 4 is “the evening hymn” because of this

last line, because of David’s enviable drowsiness. Surely, one mark of the “blessedness,” which

is at the heart of Psalm 1, is the ability to turn out the lights, shut one’s

eyes, and, without a ripple of anxiety, fall off to sleep.

But there is too much blood in David’s stories to assume that what he is claiming is what he felt every last

night of his life. I’ll bet the back

forty that he wrote this song on one of his good days. In fact, Psalm 6, just two more down, sounds

like some other guy altogether (“. . .all night long I flood my bed with

weeping and drench my couch with tears,” vs. 6).

Last weekend, my son-in-law suffered something he called a

migraine. Whether or not it was remains

to be seen, but the doctor he saw for the headache calmly suggested that he cut

down on stress. We giggled when he told

us what the doctor had offered, as if cutting down on stress is as easy as

trimming toe nails. Sure, Doc, and just

exactly how do you suggest any of us do that?

There is an answer here, of course. What David tells us in this song isn’t a lie

or even a half-truth. He doesn’t just

say, “Get some rest and call me in the morning.” That’s not what’s going on here.

In truth, sleep is a precarious time because we give

ourselves up to something we can’t control.

No one wants to snore. I don’t

think I’ve ever met anyone who wishes to have nightmares or suffer bizarre,

buck naked hikes through public places.

No one would choose to do their hair in the style we daily wake up

with. I wouldn’t wish insomnia on

anyone; but all of us, at one time or another, have trouble sleeping in part because

when we’re out cold, we’re simply not in control; and if there’s one thing all

of us want in life, it’s control. You

don’t have to be a control freak to fear chaos.

We all do.

Here—on the night of this particular song—David claims he

nods off easily. You alone, Lord, he

says, allows me to check out in ease.

That out-of-controlness that

we give ourselves to every night is, in David’s mind and heart and soul, a

piece of cake because he knows (and that’s a word we employ in the biblical

sense) God’s hand is beneath him, gently rocking.

As Shakespeare might say, there’s the rub. For those of us who know the Lord,

sleeplessness shouldn’t be a problem—and we know it. We should be able to hit the sack and

fall like a rag doll into the arms of the Father. We should be able. . .we should. And saying that is itself a recipe for even

more anxiety.

But it’s the goal.

That’s the blessedness we all want and ask for in those furtive moments

when, in bed, we feel the shakiness we so much wish we didn’t have.

For that malady, David says what we all know but need to

hear time and time again. In his

testimony there is the brace of faith God himself tells us: “Be still and now

that I am God.”

Be still, then go ahead and turn out the light.

Saturday, July 28, 2018

Friday, July 27, 2018

John, Next Door*

School was less than a block away when I was a kid, so I walked, every day, sometimes out the front door, sometimes the back. I went home every noon for lunch.

That’s when I saw what I did. I was walking back to school after lunch when two men lugged a body out of John’s house. On a stretcher–that’s what I remember, the body covered with a sheet. Completely. I was maybe a fourth or fifth grade kid, something like that, a few summers away from what the church used to call “the age of discretion.”

An old couple lived there, just a man and his wife, right across the alley. I don’t remember him as jovial or even all that friendly. We knew the old folks in the neighborhood who could–which is to say couldn’t–be teased. Step anywhere close to Mrs. Lensink’s garden, and she’d be out that back door and all over you. John and his wife were only rarely visible.

John worked for the city, for a man–a relative, my mom used to say–named “Hard.” That’s all I knew. I was a kid.

But that afternoon I knew either John or his wife was dead. The body was covered on that stretcher.

My parents didn’t try to keep me from the truth. They talked about it that night at supper, in a hushed distress that made me fearful because I wasn’t accustomed to seeing my parents so distracted. Neighbor John had hung himself in the basement of his house, the house right across the alley.

Suicide.

I don’t think I’d ever heard the word suicide in a context in which the victim was someone I knew, but his being lugged out of the back door of the house and calmly carried into an ambulance, no whirling lights, has stayed with me for sixty years. That picture came with another, one I never witnessed but still see: an old man hanging from a ceiling rafter of the house just across the alley. On summer Saturdays John mowed his lawn right there on the other side of our white picket fence. I barely remember him, his personality, his character; but I’ll always see him down there where his life ended.

There are more such stories after all these years. A man, once a friend, but a guy I hadn’t seen for years, someone who will always be a smart kid with a sharp sense of humor, good-looking, Beatle haircut. He hung himself in his garage, I heard.

Years ago, I wrote a story about a young woman flirting with taking her own life. Just to get there in my imagination was really tough because it was very difficult to attain the depth of despair she would have had to reach to consider leaving life behind. I don’t remember the story or the title, and I’m sure I never finished it. But just trying to go there in my imagination darkened my soul in a way that I’ve not forgotten.

A while ago chairs and desks and tables in the recreation center at the college were strewn with cards like the one up there at the top of the page, a sweet little image/message designed to speak kindly to the students just returned to school. I picked one up.

“We keep going and we go together,” that card says on its backside, and more. “Above all else, we choose to stay. We choose to fight the darkness and the sadness, to fight the questions and the lies and the myth of all that’s missing.” Life is worth living is the simple sermon on that simple card that announces World Suicide Prevention Day.

Almost 45,000 Americans died by their own hands last year; seven of ten of them were white males.

There’s no story I’m not telling you. I didn’t lose a brother, a daughter, a relative, a really close friend, a mom or a dad. In any very close sense, I’m not a victim of suicide. But in the close-knit world around me, two men I didn’t know and never met just quit on life in the last month or so. They weren’t friends, in all likelihood didn’t know each other; but they both took their own life. For once, the little country church not so far from where we live overflowed with people, one woman told me–it was just full of mourners.

Me? I won’t forget the time two men carried John’s covered body out the back door of the house across the alley. It’s not something I choose to remember. I just do.

We’ll see you tomorrow.

________________

*An earlier version of this story appeared here in 2014.

Thursday, July 26, 2018

Morning Thanks--Sunflower

It was late in the season, almost September, and Lowe's was getting rid of it leftover greenery--fifty, maybe 75 percent off everything. I was--and still am--on the look out to add color to our acre of field grass, so I took a couple of gnarled sunflower plants, even though the tag said they were annuals. At that price, I thought, I can still get some sunlight out of 'em for a month or so.

They didn't do much last year, stayed down close to the earth, bore me a couple of big open faces, probably paid for themselves in shy showyness. So much for that, I thought. At least they didn't break the bank.

I'm coming late to tending the backyard. In what seems a previous existence altogether, I put in a garden when we lived in a house with an open space. Our last place, a sweet old "arts and craft" house, was entirely shade, but that earlier place had a backyard open to the sky.

But that was it. At 70 years old, I'm a rookie. Honestly I had no idea that anything would come back from those end-of-the-year losers no one took off the tables in the summer. They were annuals--the tag said they were annuals.

But they were sunflowers, and while their blessed roots miraculously regenerate, those old fells left seeds that got themselves christened by life itself and, viola! today I've now there's a monster out back that, soon enough, will memorialize Wilt and Stilt. Look at him. He's huge, and the kid is still growing--a dozen flowers right now and Lord knows how many other buds awaiting the call.

Just last year, South Dakota produced a billion pounds of seeds to lead the nation in sunflowers. North Dakota was second, Kansas and Colorado right behind. South Dakota farmers weathered some pretty extreme drought last year, but sunflowers, like this behemoth, barely work up a sweat.

There can be some problem with disease, I'm told, but it's not unmanageable. The toughest lesson one Kansas farmer learned when growing 160 acres for the first time was the problem with dry down--blasted plants just don't want to quit.

Doubt it? Check out that monster up top once more time. I didn't even know he existed in April. He came out of nowhere. I bought him weary and heavy-laden at a huge discount; a year later he casts a long shadow over everything. I get why some Dakotans like 'em. They refuse not to grow. Life itself is a miracle, don't you think? What a gift.

There's this too, of course. I mow my lawn and two days later the crab grass rises skyscraper-like, as if energized, as if, in its own opinion, it's angry about having spent far too much time under cover. Boom. You can almost watch it grow. Ugly stuff. Today I got to pull it out. Even if I do, it'll just come back. Life. It just won't quit.

But dawn is coming later now every morning. To say there's a chill in the air right now is overstating, but much of summer's scorching heat is safely behind us. Lots of things out back have flowered, leaving behind spindly carcasses that weeks ago, in flower, turned the backyard into an impressionist canvas. Today, almost lifeless, they remind anyone who spots their frailty of the old adage--sic transit gloria mundi.

I don't know a whole lot of Latin, but that phrase has meaning even if I don't know the words.

A guy came to visit a couple days ago. He took his fancy scooter, he said, because his wife was gone, which enabled him to sneak it out of the garage--five miles or so from his place to ours. I'd never really seen him walk before. It wasn't pretty. When he'd stand, he'd have to lean against a railing or the back of a couch simply to hold himself. He had Parkinson's, he told me. I didn't know that, but that he had something debilitating was painfully obvious.

"I'm eighty years old," he said, a kind of proud grimace across his face.

"I'm seventy," I told him--and reminded myself gamely.

Even when you stand beside a sunflower, there are moments in the life of a retired old buck, that you repeat that old Latin phrase like a mantra. Even with all that strength, all that power, all that flowery glory, you can't help but remember there'll be a winter soon. Nothing will grow.

That's sure.

No matter. This morning, I'm still thankful for the miracle of that towering sunflower. Bought it at a discount, too--or did I tell you that?

Wednesday, July 25, 2018

Worn out

Anyone who attends the words of our President is wheezing, hands down on knees, sucking breath. It's a year and a half into his reign, and I'm shot. His adoring admirers have claimed, almost since the beginning, that you only need to take his ideas seriously, not his words. No one ever believed Mexico was never going to pay for "the wall," they'll say; but at least Trump was going to do something about a million brown faces sneaking over the border and taking our jobs. That silliness about Mexico picking up the bill--that was just fun. Smile, they say. They're probably right.

Many millions still believe Trump is a big barrel of joy. Nobody lights up the cameras like he can, after all. Nobody sucks oxygen out of every darn room of the house and even the neighborhood like Donald E. He's a lion on stage, even bigger than that huge diapered balloon the Brits floated above London.

Yesterday, for no apparent reason but his own, he adopted a whole new Russia strategy. Makes your head spin. He's now believes Russia is going to mess with the 2018 election, even though they haven't before (he says). The new dispensation begins with the solid fact that Vlad hates him, even though just last week Putin told the world he wanted Donald Trump as President because Trump was going to bring back whatever glory days existed between the world's two biggest nuclear arsenals.

In fact, the White House went out of its way to expunge some of that exchange from their transcript of that Helsinki moment AND edited the official video of the exchange, as if the entire comment was never spoken, even though it was and is plainly evident in a thousand other recordings.

The man lies. Constantly.

It's ridiculously easy to be Orwellian about all of this. When is a pig not a pig? When the pig says he isn't a pig. Then who do you believe? Why, on the Animal Farm, you believe the pig.

Maybe he didn't even need to say what he did yesterday, among the cheekiest lines he's ever delivered. The American public shouldn't believe their eyes and ears, he told the cheering VFW crowd. "What you're seeing and what you're hearing is not what's happening." Don't believe what you see and hear. Believe me. Hmm.

Welcome to the Twilight Zone.

The most powerful man in the world has us knee-deep, maybe deeper, in the barnyard, and you just can't walk around too long in that level of excrement before you get really, really tired.

The flat, business-like quality of the taped conversation between the man-who-would-be-President and Lieutenant Cohen suggests an ongoing relationship between Trump and his hit man designated to take care of poisonous or inflamed incidentals, suggests also that there are more such incidents.

Clearly, Donald Trump had a relationship with a woman he swore he'd never met.

So did Clinton, you say? Yes, and Clinton got impeached. Nowadays, good Christians won't let that happen.

The truth is, we're all wasted, out of breath, and tired of the never-ending string of breaking news stories. Donald Trump beat the libs in the last election, but he's now beaten all of us because every last Trumpian moment, and they are legion, is a muddy four-inch headline.

Tuesday, July 24, 2018

Small Wonder(s)--the great killer of the Great War

When Edgar Hartman came down with the mumps, it laid him up for a month. That may seem unlikely. Mumps? Hartman was a 26-year-old soldier who'd just completed basic training and was actually aboard the ship and awaiting departure when he got hit with what most of us think of a simple childhood disease.

But for a month, my great uncle Edgar lay in an army hospital, flat on his back, fighting a monster. "I was a sick boy last week," he told his sister in a letter, among the last he would ever write and she would ever read, "but I'm feeling a little better now but am very weak guess you can see that on by [sic] writing."

Chances are, he wasn't alone in that army hospital. While others may well have suffered from the mumps, in all likelihood, the infirmary was swamped with sick doughboys, victims of what no one understood right then to be the pandemic it became, a virus often referred to as Spanish flu, an illness that had little to do with Spain and killed millions.

One hundred years ago, the United States of America lost thousands on European battlefields when we entered "the Great War" to help Allied powers defeat the Kaiser's entrenched hosts. It's probably fair to say that the U.S. came to Flanders Field with a strain of naivete that other countries shared, glorious undying patriotism, banners unfurled, war as manly duty.

All of that changed. The war killed 116 thousand young Americans, but it sickened many thousand more, emotionally and spiritually--and physically.

As unlikely as this may sound, ten thousand more doughboys succumbed to illness than died in combat. Amazing. My uncle died on on the Vesle River, in what his obituary calls "the great drive." He took shrapnel in the side, one of this country's 53,000 combat deaths--63 thousand died from disease. You read that right.

War preparation was a recipe for disaster. Training camps like his, Camp Greene, Charlotte, N.C., brought together boys from rural Wisconsin and far away South Carolina, from the plains of western Kansas to the boroughs of New York, each guys potentially carrying hybrid viruses and varied immunities that training camps thus blessed into breeding grounds for new and robust germ enemies.

Troop ships were jungles, hot houses of disease. Lock up a thousand boys on a long cruise to Europe, and it's altogether reasonable to expect strains of influenza to move into and through all those bodies, forming its own horrifying wave. Measles and mumps prospered among young men weakened by flu. Just as training camps had, troop ships mixed up men from all over the states, each of them carrying varying flu strains. Fighting disease was even more difficult in close, wet quarters.

Writing in the Atlantic in 1918, Henry A. May described a troop ship's atmospheric recipe for disaster: "The absolute lassitude of those becoming ill caused them to lie in their bunks without complaint until their infection had become profound and pneumonia had begun." Nose bleeds were wholesale.

The severe epistaxis which ushered in the disease in a very large proportion of cases caused a lowering of resisting powers which was added to by fright, by the confined space, and the motion of the ship. When pneumonia set in, not one man was in condition to make a fight for life.Still today throughout Siouxland, old cemeteries include whole flights of stone markers over graves of men and women and children--especially children--who died in 1918 and 1919 from successive waves of influenza that took down and laid up one quarter of the entire American population and dropped our national life expectancy by a dozen years, killing 675 thousand. Worldwide, Spanish flu killed 50 million.

My great uncle Edgar missed his company's departure for Europe, spent an additional month fighting instead a cruel bout with the mumps. He got to France a month before being killed in a gully in an open field in France.

Odd as it may seem, the real killer, the mass murderer of the era wasn't "the Great War," "the war to end all wars."

It was a bug, a virus. The flu far more ruthless killer.

Monday, July 23, 2018

Morning Thanks--prairie purple coneflowers

Haven't a clue who discovers such things, but I read somewhere that the petals of the purple cone flower do wonders on sunburn. Haven't tried it, but the idea has feel of authenticity and may well be one of those old wives' tales as worthy of attention as the old wives themselves.

True or false, coneflowers are greatly welcome in our garden, not simply because they set the place ablaze in a pinkish purple that's sweetly becoming, but also because they're home out here. Against a bed of grasses, when they bloom as they can and do, they do so with true native dignity because this is where they're supposed to be, where they belong, where the Creator, himself a fair-to-middlin' gardener, destined them a place.

Long ago I was told you can't expect native flowers to be as showy as their pampered greenhouse cousins. Take a walk in a meadow and you must needs define beauty in a whole different way, smiling at what seems something less than profusion. Getting more with less--that sort of thing, you know.

This confusing weather year--way too much water, a ton too much heat, and the whole growing season begun with an out-of-the-blue record freeze back in April--has nonetheless blessed our coneflowers, both the ordinary garden variety, as well as their more rural cousins, the pale purple ones out back. All around our place, they're doing better than well.

They're bee magnets, too. They rely on long-tongued bees, I'm told, to propagate. Bring on the bees, I say, the more coneflowers the merrier around here. Go ahead and burst forth in purple profusion. They're the joy that all that blasted weeding is about. Go ahead and shine, boys and girls.

Come on out and play. Come on out and do your own thing. Carpe diem.

This morning, consider the purple prairie cornflowers. They toil, neither do they spin; and I'm thankful for 'em, every last one, yours and mine.

Sunday, July 22, 2018

Sunday Morning Meds--You're covered

“Blessed is he. . .whose sins are covered”

After far too much traveling, I

have come to the conclusion that motel rooms are not designed for people my

age; they are decorated with entirely too many mirrors. Wherever you look, full length panels of

reflective glass offer you entirely unbidden views of your own sad and sagging mortality.

One of the reasons English TV comedies are more fun than American

sitcoms is that English audiences, it seems, don’t demand physical perfection. English comedies regularly feature unhandsome

people; but American television offers a persistent diet of perfect shapes,

both male and female, so many, in fact, that one begins to believe that such

pulchritude is the norm. Given all that

gorgeous flesh, suddenly seeing your self bare naked on a six-foot wall is an

epiphany of horrific proportions. A few

weeks ago I came home and told my wife I would never eat again.

I suppose I shouldn’t be equating sin with the body. Someone

told me recently of a new study which maintains that John Calvin’s despairing views

of the sins of the flesh was attributable, in part, to the revulsion he felt

about the debilitating hemorrhoids he fought through most of his adult

life. If that’s true, it’s something I

wish I didn’t know.

But there is a link here in this verse from Psalm 32, at

least in my mind. The exuberance of the

line bursts from the realization that something repulsive is wholly taken care

of, covered up, covered over, out of sight and, better yet, out of mind, even

out of soul. That something isn’t

nakedness, but it’s close.

Sin isn’t so much an act as it is a condition, like dandruff

or flat feet. Sin is something we never stop fighting. There’s no truth, says

the Apostle Paul, in those who claim they have none.

But the blissful joy of the opening lines of Psalm 32—or so

it seems to me—is not the blessed realization that our sinful condition is gone, but instead our

blessed assurance that God’s forgiveness has it covered—as in, “not to worry,

fella, I got you covered.” Our greed, our neglect, our thievery, our hate, our

drunkenness, our adultery, our pathetic pride, our green-eyed jealousy, even

our pride—sin in all its pathetic naked horror, even the one we can’t forget,

the one that haunts us, makes us sick unto death, that sin is covered because

He’s got our back.

David’s sins were legendary in the unsavory mess created

when he couldn’t keep his royal hands off someone else’s wife, and then“covering”

that sin by the sleazy murder of her beloved.

All of that is gone, David himself testifies here in Psalm

32. It’s history. All that’s left is grace. Even though I should cut back on the snacking, it's a blessing to remember that, with grace, we're forever more than what we see in a mirror. We're covered--that way too.

That’s the story, David says. Praise the Lord.

Friday, July 20, 2018

Won't You Be My Neighbor? -- a review

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/59991295/neighborcover.0.jpg)

There may be other teachings more central to the Christian gospel--I don't care to fight or argue. But I can't help thinking that no tenet is so radical, so "out there," so impossible, as this one: every last human being, not some but all, even the villains and most vile, have somewhere within them an authentic fragment of the the Most High, the likeness, the very image, of God. We are all image-bearers. All. Every last one.

Its corollary is equally unreasonable: because we carry that image, we deserve respect, even love. All of us. "Do unto others as you would have them do unto you"; "love your neighbor as yourself."

Really? Get serious.

I spent time in front of the TV when our kids were little. In the morning I watched my share of Sesame Street because they did. It was the eighties, and every afternoon Fred Rogers would walk into his cheap, utilitarian set, take his jacket off his shoulders, pull on a cardigan, feed the fish, and sing some silly ditty. Our kids were mesmerized.

And I giggled because Fred Rogers' TV presence was totally absurd. He should not have had millions of viewers. Nothing happened in his blessed neighborhood. No fireworks. No pratfalls. None. No conflict. No Oscar the Grouch. Just a few neighbors who dropped by and a couple of hand puppets leaning out from the same old holes in the wall.

I never gave him mind really, but I often sat there in astonishment at my kids' astonishment. By any measure at all Mr. Rogers' Neighborhood shouldn't have even been on the tube. Fred Rogers had to have been the only person in TV land who believed that helping kids understand themselves and the world around them meant quiet reassurance in the repetition of ordinary things accomplished in love and tolerance. He should not have had so many viewers. My kids wouldn't miss it.

Right now, it's difficult to imagine a more worthy contemporary beatitude than Won't You Be My Neighbor?, a documentary film on the life of Mr. Fred Rogers. It's a wonderful testimony, as beautiful and moving a sermon as Michael Curry's remarkable address recently at the royal wedding, a shocking reminder, seriously, that the Truth of the Gospel is as stunning as it ever was.

The Christian world would do itself and its Lord a favor next Sunday to simply forget worship for a week and gather instead to watch this movie because Won't You Be My Neighbor? delivers the goods in a fashion that preaches a gospel beyond words.

Fred Rogers was as human as any of us; Won't You Be My Neighbor doesn't skimp on his weaknesses. But it directs us all toward the central value of his life and work, the doctrine of Jesus that insists we are all image-bearers, all of us, even the least of us.

Behold, I have a dream--that all of God's children, evangelicals and Catholics, Mormons and Pentecostals, Trumps and No-Trumps, evolutionists and creationists, black and white and red and every hue between, gather in churches some Sunday morning soon and, all together, watch a movie about a strange guy who tried to live the gospel truth. Forget liturgy and music and performance. Every believer from every tribe and nation simply watch, together, "Won't You Be My Neighbor?"

Oh, happy day.

Thursday, July 19, 2018

Morning Thanks--?????

This shot stays on the shelf. Down here in the basement, the walls are full of canvas photographs. In a spare room behind us, a couple dozen wait to rotate into the lineup next time I change the set. In the last 15 years, I've taken hundreds, even thousands of shots, just like everyone else with a cellphone.

But this shot, now 17 years old, stays in a frame on the shelf, not because it's the best photograph I've ever taken, but because the moment was so profound and so unique, that like the photo itself the moment stays, front and center, in my memory.

We'd been adequately warned. People had told us we'd go stark raving mad being grandparents. Time and time again people would say it. I wasn't a Doubting Thomas exactly--I didn't pooh-pooh their obvious joy. I just smiled as they were braying and waited for the conversation to steer itself elsewhere.

Then it happened. Sure enough, they'd spoken the unvarnished truth: there are no words to describe what it felt like to see my daughter hold her own baby, my own--our own--first grandchild. That picture conjures the thrill of that moment. I'd been warned, but I was still unprepared for the flood of whatever grand emotion washed through me.

And now there's this one.

The truth is, we've already got a hundred pictures of this little dear. They flow magically into an on-line album full of precious shots I've never touched; but here the two of them are on a double-wide screen in front of me, an image of yet another firstborn, my son's. Like I said, I've got a hundred pictures already, and she's barely six months old.

But this one does me in. This one is special, not because it is clearly some talented photographer's creative genius, but because my daughter-in-law's cellphone-shot from the bathroom fills the screen with joy. He's vacuuming, he's smiling, and that darling grandbaby couldn't be happier.

Gorgeous.

If I knew exactly how to say it, I'd give thanks this morning for what last night's new picture does to my soul, filling it with an emotion that's as fully human as it is gloriously divine. It's life. And life itself is such a gift.

Wednesday, July 18, 2018

When Hitler wasn't Hitler

Hitler, you know, wasn't always Hitler.

His boyhood wasn't ideal. The old man used to beat on him, used to think his son didn't have a clue about life. When Adolf told him about wanting to do art, the old man sent him to technical school, where he became, quite predictably, a failure.

During the war, the First World War, he was a hero. He suffered significantly, gaining the Iron Cross, the German equivalent of a purple heart, and more. He loved the war with an affection that isn't wholly unusual among some vets--nothing in life, after all, tests the spirits like the actuality and immediacy of death. And he came back angry, confident Germany lost the "war to end all wars" because pointy-headed intellectuals--Jews and Marxists and whoever else--signed the damned armistice.

He took on his anti-Semitism despite the fact that his wartime commander, the man who had recommended he be decorated for bravery, was Jewish. But he wasn't alone. Anti-Semitism in Europe--and America--wasn't rare. As early as 1919, historians claim he held the belief that Germany's problems began somewhere inside its Jewish population. But Hitler still wasn't Hitler.

He took up with the fledgling Nazi political party when he left the military in 1920. That infamous red Nazi flag with the swastika against a white background in the center?--Adolph Hitler, the artist, designed it. The party itself inflated its rolls to make it appear much bigger than it was. In the political system post-war Germany, it wasn't really much of a player.

He started doing some public speaking when party official noticed his oratorical skills. When conflicts arose in the party, Adolph told the others he was leaving the Nazis. His superiors knew very well that no one else had Hitler's speaking skills. They capitulated, and Hitler took over the party. That's when Hitler began to be Hitler. People--in significant numbers--began listening when his fiery oratory played on nationalist themes, when he derided the scapegoats who kept Germany down, when he appealed to people's sense that they were being left out of the game altogether.

President Donald E. Trump is not Adolph Hitler. There are no plans in his desk drawer for crematoriums going up behind forests, human death camps. He isn't about to invade Canada and Mexico, our neighbors. He isn't thinking seriously about ruling the world.

But unlike any President in memory, he has an ego that seems insatiable. His absurd apology yesterday was as well-meant as any other falsehood he's fabricated, thousands of them. His performances throughout last week--NATO to Helsinki--made clear that he respects only one person, Vladimar Putin, for reasons no one understands.

You can say what you'd like about any past President, from Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who wanted to pack the Supreme Court, on down to Barack Obama. What you won't find is anyone so willing to consistently bend the truth as President Donald E. Trump. No one comes anywhere close in sheer voluminous ego. I think Donald Trump would believe, if he thought about it, that he, like no one else, could rule the world.

That's new in the pantheon of Presidents. Time alone will tell if its truly scary.

Right now, there are moments when it's risky not to believe it is.

Tuesday, July 17, 2018

Small Wonder(s)--Freedom

Seems easy enough, doesn't it?--simple and true: once you're free, there's no going back. You're free, free at last. Makes sense. Even a kid would understand.

Well, not so. In the case of more than one slave and former slave, being free for a time, or having been free for months or even years, was not a ticket to ride because, by law in these United States, it was altogether possible and perfectly legal for a free man or woman to be locked up in slavery once more, improbable as that may seem.

And yes, in case you're wondering, I'm talking like a white man. To describe this change--from freedom back into the slavery--as improbable is unfeeling, even racist. Slavery was not a condition, like athlete's foot. It was evil, inhuman.

In the 1830s, historical records make clear that Minnesota's Fort Snelling was home to a dozen slaves, maybe more, people who cooked and cleaned and did whatever work white military brass, their masters, deemed beneath them. Technically, they weren't slaves at Ft. Snelling; in the Wisconsin Territory, slavery was banned. But when officers were reassigned, they took their help along; and, if they went south, those free men and women once again, by law, became slaves.

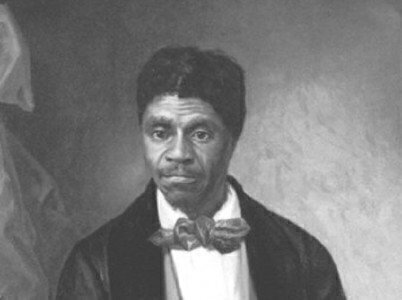

Dr. John Emerson, a physician, owned slaves, two in fact, a married couple, Dred and Harriet Scott, whose basement apartment you can visit if you stop sometime at Ft. Snelling. It's not a hovel--it's tiny, but then, in the 1830s, Ft. Snelling wasn't the Hilton.

It wasn't there where Mr. and Mrs. Scott started down the long road toward freedom, but it was where they two of them met and married. For the record, Mr. Dred married Harriet, but Dr. Emerson bought Harriet Robinson. (Stunning kind of sentence, isn't it? Dr. Emerson bought Harriet Robinson.)

Slave genealogies get complicated, so stay with me. Dr. Emerson died when they were all in St. Louis. By law, his wife inherited her husband's property, including their slaves. When she chose to hire them out, Dred Scott tried to buy his freedom, to pay to be free, but the widow Emerson wouldn't sell him to himself, or them to themselves. They were slaves.

It was 1843. To call slavery an issue back then understates too. Even though the American Civil War was still 17 years off, true believers on both sides of the issue of slavery were ready to die. Dred and Harriet Scott, slaves once more, took their case for freedom to the courts.

But for them, justice was neither speedy nor justice at all. The Dred Scott decision, handed down from the U. S. Supreme Court on March 6, 1857, denied freedom to the Scotts and their two daughters, when Justice Roger B. Taney, writing for the majority, determined that Dred and Harriet Scott and their daughters, Eliza and Lizzie, were, simply stated, not human.

It's not complicated. Dred Scott and his family were kept in slavery because fourteen years after the Scotts began to suit for their freedom, seven U. S. Supreme Court justices ruled that black people could not be citizens of the United States of America because in 1787 the U. S. Constitution maintained that Black people were not citizens.

It's not complicated. Dred Scott and his family were kept in slavery because fourteen years after the Scotts began to suit for their freedom, seven U. S. Supreme Court justices ruled that black people could not be citizens of the United States of America because in 1787 the U. S. Constitution maintained that Black people were not citizens. There are a ton of reasons to visit Minnesota's Ft. Snelling. It's a huge place with canons that still rock the stone walls when lit and fired. There's eats and treats galore on any weekend. Visit the hospital, the officer's quarters, or take a stroll on the grass of the parade grounds. The Mall of America isn't far away.

But it will do your soul well to step into a little basement apartment--it's neat and clean, the walls adorned with utensils of the age. It's the place where a slave couple lived, long ago, in another age, a man and a woman who spent fourteen years fighting to be free, only to be denied by the most appalling verdict ever laid down by the highest court of our land: "no, you can't be free."

There's a tour guide who'll tell you about Dred and Harriet Scott. She'll tell you the story. She does a good job. Get the kids to listen.

Seriously, get the kids to listen.

Monday, July 16, 2018

Dreams and sweat

Things were more loosey-goosey back then. What I remember is that he was there for just a week or so before announcing he had to go to a funeral or something, not just across town but out in Idaho or Montana, halfway across the country. He'd be gone for a couple days.

Must have been a long funeral. He didn't get back for a month--which meant I was stuck with his students--me, the student teacher. His leaving me alone like that would be unthinkable today.

I must have been cocky because I don't remember going pink or anything. He told me what needed to be done, and the task must not have seemed particularly daunting: teach high school juniors and seniors something or other or speech and theater--theater history. That was a half century ago.

I didn't need a supervisor to know I was doing okay as a teacher. I knew I was okay because students thought I was okay. Their attention, their caring, clearly registered. By the time the guy came back, I'd learned what student teaching should teach--that I could do it and like it.

Six months later, when I stood in front of my own classroom for the first time, I was more nervous than scared. I sort of knew that teaching was something I could do.

It became something I did for the next 42 years. Only twice in that time did I consider leaving the classroom, and not once in all that time did I feel trapped; and, for 37 of those years I was in the same place. You'd have thought I'd rot. I don't think I did.

For some reason, it's not easy to type out this sentence, but I'm going to: I loved teaching.

Did I know that going in? No. I had to learn to teach and learn to love it.

Carol Dweck, a psych prof at Stanford, claims that one the phrase "find your passion" appears nine times more often in speech and writing these days than it did a quarter century ago. "Find your passion" has become, she explains, the clarion call of career councilors, who tell kids looking for a place in life that finding a profession is something you'll know when you see it, something, well, like falling in love.

Dweck and her research buddies claim that's hooey. People get good at something, become experts, not by some vision, some unsolicited epiphany. Interests develop by use and experience. Passions bud and flower from curiosity and plain old experience. I think I learned to love teaching by teaching. Whether or not teaching was "in me," was less determining than my standing up there, day after day, having to get the job done.

In those early years, we lived just a few blocks from campus, close enough to walk, which I did, often with a colleague and friend. We were both young, both writers, both people who loved literature. More than once as we were telling each other stories about what had happened that day in the classroom, one of us would bring it up. "Just think," we'd say, snickering, "we get paid to do this."

Not much, but a salary was icing on the cake.

I think Professor Dweck is right: Loving teaching, at least for me, was not an instinct. I learned to love it. I found my passion by going back, day after day, into the classroom.

Passions aren't discovered; they're developed.

Sunday, July 15, 2018

Sunday Morning Meds--Wants and Needs

“I shall not want” Psalm 23:1

My friend

Diet Eman, who spent more than anyone’s fair share of time in a concentration

camp in the occupied Netherlands

Food. There was so little of it, that when what

little of it emerged, the guards stood by closely. She describes those moments in Things We

Couldn’t Say:

The only time they watched us closely was when we got our bread because resentments could grow and tempers flare. If you were assigned the duty of cutting margarine, you had to be very careful that all the lumps were exactly the same size. Margarine was all we had—no jam, no marmalade, no nothing—just bread and a little pad of margarine. You had to be very careful slicing it because the others would watch very closely to be sure that no one pad was any thicker than the other. If one slice would have been a bit thicker chunk of margarine, there would be bickering for sure; when you’re hungry, such bickering comes up easily.I don’t need to document the extremes to which good human beings will go when hungry. Reason gets tossed like cheap wrapping paper in the face of real human need.

Truthfully, I’ve never been hungry. Neither have my parents, although, during the Great Depression, they came much closer than I ever did. My mother told me about my grandfather, a squat big-shouldered blacksmith, crying at supper because during the Depression neither he nor his farmer customers had any money. There were times when he didn’t know where his next dollar was coming from. My father, whose father was a preacher, remembers his parent’s cupboards being filled only by the largesse of his congregation. There was no money for a salary.

In my life, “I shall not want” seems a given. I don’t need a God--I’ve got an Amazon Rewards Card. In the many years of our marriage, our economic problems have arisen not because of lack of money but because of too much: if our kids need something—our adult kids—should we buy it for them, or make sure they learn some basic lessons in economics? Sometimes—often—our hearts lean a direction our heads tells us isn't smart. That still happens. Most the time our toughest questions concern what to do with extra.

I just now horribly misspoke, of course. We have money all right, but our cushioned pocketbooks don’t mean we don’t need God. If we'd like, every week we can eat the America's finest steak (we live in beef country, after all); what’s more, Sioux County has the finest pork loin in the world. Food is no problem.

But we want—good Lord, do we want. We want our kids happy. We want a deeply fractured nation healed somehow.

We want to ease into old age. We want another good year for ourselves, a good life for our kids and grandkids, strength and patience and grace for our dad who's 99 years old.

“I shall not want” may be the most audacious claim in all of scripture because, good Lord, do we ever.

Good Lord, do what you can to help us not to.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)