["From the museum"--11/11/10. Occasional old posts from yesteryear. Life has changed; some stories endure.]

I was never formally introduced to my great uncle Edgar Hartman. He was dead long before I was born, even before my mother was born, in fact. But I knew of him by way of his only sibling, my grandmother, who used to tell me the same story, over and over, whenever I, as a boy, mowed her lawn.

A single ice-cube floated around at the top of a glass of lemonade she’d always bring out when I’d finish the grass on the north side of her house. She’d set that lemonade out, wave me to the porch beside her, then push that glass at me with a warning.

“You drink that slowly now,” she’d say. “Years ago, I brought my brother Edgar a quart jar of lemonade when he was working in the canning factory–one of those hot summer nights.” Her head would rise slightly, her eyes lose focus as she’d bring back the incident. “Edgar drank it in one gulp–never even brought it down,” she’d say, not without some admiration. “When he was finished he took one look at that empty jar and passed out–right then and there, flat on the floor.” She’d point at the lemonade. “Not so fast now.”

That was just about all I knew of this great uncle Edgar. I knew he was dead, of course, and that the local American Legion Post was named after him–Hartman-Lammers Post–and that he’d died in the Great War, World War I.

I was a kid then–maybe ten–and a half a century had passed since Uncle Edgar took leave from this vale of tears. He died somewhere in France, maybe in a scene like this—I don’t know—but for years the only story I knew about him featured a bout of heavy lemonade chugging and a quick trip to the cement floor at Oostburg Canning Factory, circa 1910.

Years later, my grandma passed along fistfulls of old scrapbook stuff to me, thinking, I suppose, that of her grandchildren, I seemed most fascinated by her stories of the past. Those old pictures and documents continued to yellow in a box I’d come heir to, each dutifully described in her chicken-scratch writing so I’d remember who was who and what was what.

When Grandma died, I dug into that box and found a bunch of things having to do with her brother Edgar. Odd. I was 500 miles from the Oostburg Canning Company and American Legion hall, but here I was, fated to be the sole caretaker of a life most everyone else had forgotten.

Edgar Hartman was not married when he was killed instantly by what his commanding officer called a German “one-pounder.” He was just one of millions killed in the endless horror of trench warfare that came to define the military madness of World War I. My mother never knew him; she’d been born a month and a half after his death. As far as I knew, no one alive knew my uncle Edgar.

I suppose that’s why I put all those Uncle Edgar documents, photographs, and letters my grandmother had given me into a scrapbook with “Photo Album” embossed in gold across a non-descript, tan cover. There’s no picture of him sprawled out on the floor of the Oostburg Canning Company here, but there is, quite frankly, everything else anyone on earth knows of him. I’ve got all of that here in this scrapbook, so when I hold it, as I am now, I have in my hands every last shred of the life of a real human being, a man who happened to be my great uncle. You might say, I’ve got the book on Uncle Edgar.

Had I known him, I suppose I would feel slightly different than I do. Had I known him, grief would certainly play a role in way I feel when I sit here, paging through the photographs. Honestly, I don’t feel the grief my grandma certainly must have when he didn’t come back from France. For years, my mother says, our family’s attendance at the Oostburg Memorial Day cemetary “doings,” as Grandma herself used to call them, was mandatory. After all, her only brother had died in “the war to end all wars.”

In fact, my grandmother’s anguish is here vividly here in the Uncle Edgar scrapbook. You can feel it. You can see it in an old envelope that never got through to her brother, and the letter it holds, dated March 14, 1919 (four months after Armistice Day, November 7, 1918), and written on her husband’s stationary–“Harry H. Dirkse, Village Clerk,” it says; that note, written in a much livelier hand than the scratchings on the back of the photos, is signed “Your sister, Mabel.” That’s my grandma.

Here’s what it says: “Dearest Brother, Am making another attempt to have you hear from us. I have now had eleven of my letters returned to me but none the last month so will send another in search of you. We have been unable to find any trace of you up to now, nor received anything from you since your field service card reached us on August 7th. We are all well and have a fine baby girl 3 mos. old awaiting your return. Will write more when I learn whether or not this reaches you. With Love.”

The “fine baby girl” is my mother.

The field service card she refers to is here too, in my hands. “Y * M * C * A,” it says at the top, with the words “With American Expeditionary Force” beneath it. The message is terse: “Dear Sister M, Just arrived safely in England will write again as soon as I have an address. Edgar.” It is not difficult for me to imagine how closely my grandmother must have guarded that postcard over the ensuing months.

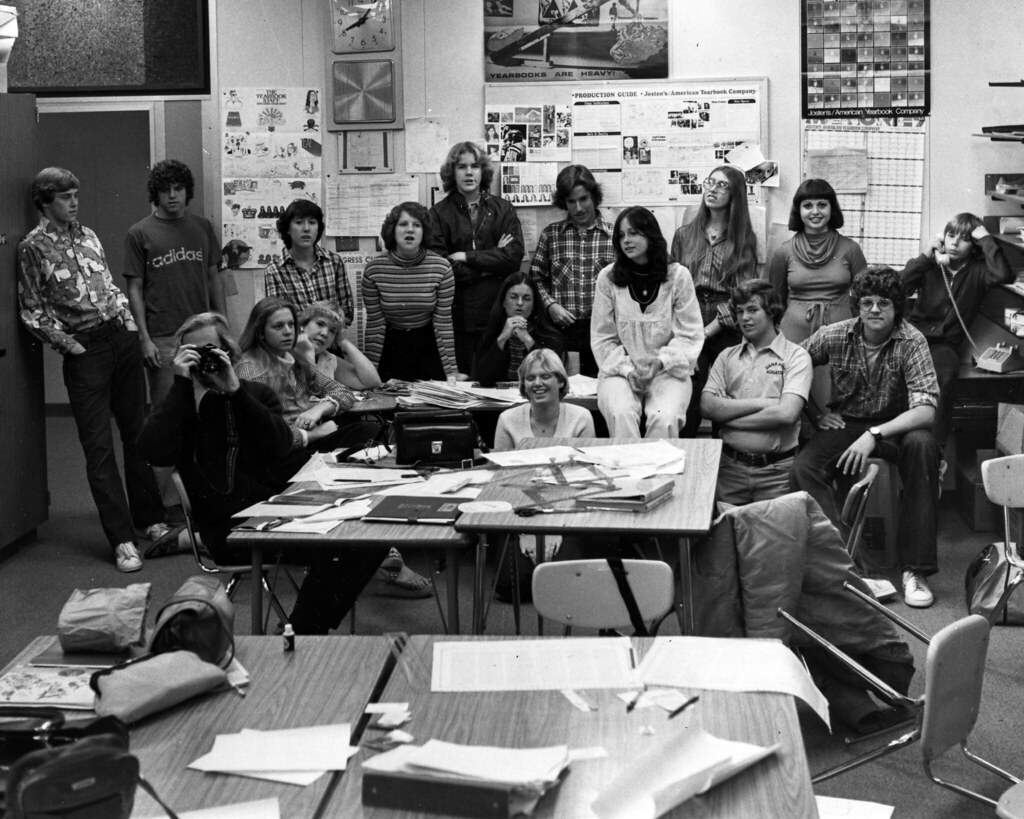

And there’s more. My Uncle Edgar scrapbook has a childhood picture of the two of them, brother and sister. There’s even a baby picture, as well what seems to be an eighth grade graduation picture taken about 1910 or so—that’s him, back row, second from the tallest. There are five pictures of him in his military uniform. In one, he’s saluting; in another, a fat cigar juts from the corner of his mouth, while he stands beside his brother-in-law, my grandfather, behind him Oostburg’s Main Street as it must have looked in the early years of the century, a horse rail clearly recognizable out front of my grandfather’s blacksmith shop in the very middle of town.

The scrapbook also includes other things—a stampless post card from Basic Training in North Carolina, which mentions having to hike fifteen miles, a number of letters, the only historical record of what was on his mind in those last years of his life–amazement at the unending length of army chow lines, news of the mumps that kept him from sailing overseas with his company in April of 1918, joy on having run into Jim De Munck, another Oostburg boy–“good to see someone from home,” he writes.

And I have here in my scrapbook the official letter from the War Department, The Adjutant General’s Office, Washington, deeply-stained and dated August 23, 1919, more than a year after his death, and almost a year after the war’s end. It’s addressed to Mrs. Harry Dirkse, Oostburg, Wisconsin, and concerns a man the army noted as “201 (Hartman, Edgar J.) CD.”

“Madam,” it begins, and then, “It is with profound regret that I confirm. . .” You can guess the news.

On the next page is another document, equally official. “Army of the United States of America,” it says in a headline that tents over the top of the page and includes the official symbol of American government, an eagle with palm leaves in one grand claw, arrows in the other. “This is to certify that Edgar J. Hartman, Private, Machine Gun Company, 58th Infantry died with honor in the service of his country on the sixth day of August, 1918.”

The date for the certificate is itself profoundly sad. “Given at Washington D. C., office of The Adjutant General of the Army, this eleventh day of June, one thousand nine hundred and twenty.”

What exactly happened to this man, shown here with two little children, one of them my uncle, the other the great-grandmother of several Dordt students, this man standing across the street from Wykhuis Store, which is now the Pizza Ranch in Oostburg, Wisconsin?

Well, his story is here too, at least what one man claims is Edgar Hartman’s story. My grandmother’s documents include a two-page, hand-written note from a man named Leo B. Zastrow, who described doughboy Edgar.

“He was a member of my platoon but was in another squad about 300 yds to the left of my squad of which I had command in a sunken road leading to Ville-Savoy they were dug in the banks of the road. We had just finished a barrage of 15000 rounds for a covering of our infantry’s advance across the Vesle River. They were fired upon by German one-pounders immediately after our barrage and according the Corporal’s information to me he was instantly killed.. . .I later seen the body when relief came to my Division on my way from the front and recognized the body only by identification tags.”

As to any last words or message, Zastrow says he has none, but he wishes to assure Mr. Hartman’s folks that “he was my most trustworthy man.. . .I can assure them that he died a ‘Hero’ [capital H]. And then, strikingly, “Hoping this information will be of value to you.”

My scrapbook also includes an impressive obituary from the Sheboygan Press, June 18, presumable 1920, which tells much of the story I’ve already related, and adds this: “In the village he was regarded as one of the most prominent young men. He was of a quiet disposition and was well liked by his friends.”

On the final page of this scrapbook is the solitary picture of a solitary cross in a sprawling military cemetery, somewhere in France, I suppose. In very light letters on the cross piece, the words “Edgar Hartman,” and the number “178.”

Edgar Hartman was one of 126,000 American doughboys who didn’t return from the French killing fields or oceanic cemeteries. He was 28 years old when he died, single, and had been employed at the local lumber yard when duty called. He left behind a girlfriend, who later married and had her own life.

It’s entirely possible that no one at Hartman-Lammers American Legion Post knows anything about Edgar Hartman, so think of this: if next June some prairie monster tornado would lift Sioux Center, Iowa, off the gently rolling plains of the American midwest, scattering the household goods of the James Schaap family hither and yon, and this scrapbook of all there is to know about Edgar Hartman were to disappear from the face of the earth, then no one could ever know much at all about the man. His story would be gone, his life as indistinguishable as his body the day that one-pounder killed him in a French ditch.

To hold this scrapbook in my hands has always been a profoundly humbling experience, not only because what’s here is all there is left of this man Edgar Hartman, but also because one can’t help realize how many others–my ancestors and yours, hundreds of millions of earthlings–have vanished from this world without leaving even a trace of themselves. My Edgar Hartman scrapbook, placed on a shelf above my desk, has become my own momento mori, an memento of death’s reality; because what’s truly humbling about having everything anyone on earth knows about Edgar Hartman between two covers of a Wal-Mart scrapbook is the nearly inescapable perception that someday each one of us will also be less than a memory.

But there’s really no big news here, is there? “Dust to dust, the mortal dies,” we used to sing, “both the foolish and the wise.” Later the old song says, “Yet within their hearts they say, that their houses are for aye; that their dwelling places grand shall for generations stand.”

I need Edgar Hartman. We all do. “No young man believes he shall ever die,” wrote William Hazlitt, long ago, and I don’t think he was discriminating.

But now, this Veteran’s Day, it’s good for me to think of the anguish in these letters, months after the Armisitice was signed at five a.m., in a railway carriage in France, November 11, 1918. It’s good for me to think of what my grandma went through, not knowing. It’s good for me to think of that anguish repeated 125,000 times in one year here in this country during and after World War I; 8,500,000 times, worldwide by the end of that war.

On this Veteran's Day, it’s good for me to remember the cost of freedom.

That’s the book on Edgar Hartman, an old story that, like the other worthwhile old stories in its genre, needs to be told over and over again until each of us recognizes it as our own.

That’s my addition—and his, this Great Uncle Edgar—to the story of Veteran’s Day.